The question of what to do about hydraulic fracturing, aka fracking, of oil and natural gas has emerged as a rich vein of debate in the 2020 race for the White House.

Several Democratic presidential contenders including Sen. Bernie Sanders, Sen. Kamala Harris, and Sen. Elizabeth Warren have proposed to ban fracking altogether, a stark shift from where the party was just a couple years ago.

“There is no question I am in favor of banning fracking,” Harris said during the CNN climate town hall in September.

Sen. Amy Klobuchar was a bit more circumspect. “I see natural gas as a transition fuel,” she said at the town hall. “It is better than oil but not nearly as good as wind and solar. I am being honest on what we need to do. We won’t immediately get rid of it.”

Activists have pushed the candidates to address fracking because the boom in hydraulic fracturing has radically reshaped the US economic, energy, political, and environmental landscape.

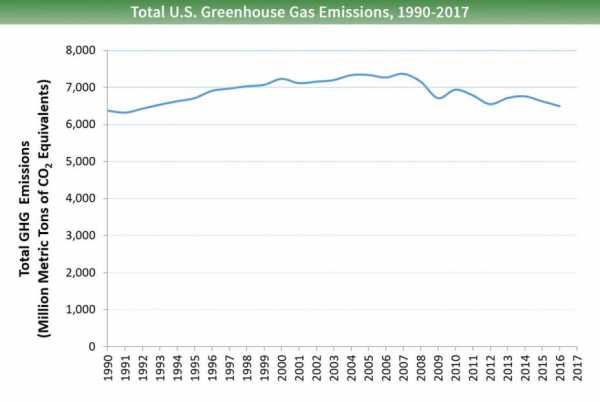

It’s turned the United States into the largest oil producer in the world. It helped pull the country out of a recession. It’s created boomtowns flush with cash in once sparsely populated parts of the country. At the same time, fracking has led to a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions in the US.

Fracking involves pumping high pressure water, sand, and other chemicals into a rock formation to create fractures that can release trapped oil and gas. It’s unlocked massive quantities of energy in the United States, but it has had some side effects.

Wastewater injection from fracking wells has caused a spike in earthquakes. It has caused local air quality and safety problems. And while they’re cleaner than coal, oil and gas from fracking are still fossil fuels.

For policymakers, the difficult choice is deciding whether the benefits outweigh the harm, and if fuels from fracking can be a stepping stone toward cleaner energy. “This is one of those issues where there’s just so much gray,” said Sam Ori, executive director of the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago. “I don’t think that there’s a really clear case that says fracking is necessarily good or bad, on net.”

And for presidential candidates, it’s tough to find the right pitch to voters, who are themselves divided. A recent poll by KFF and the Cook Political Report of voters in the key swing states of Michigan, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, showed widespread support for proposals like the Green New Deal, but much less support for a fracking ban. In Pennsylvania, 69 percent of swing voters said they support a Green New Deal, but only 39 percent wanted to ban fracking.

It’s a microcosm of the broader policy discussion about the role of the fossil fuel industry in the carbon constrained future, whether it should be fought as an adversary or embraced as a partner.

As for fracking, researchers and analysts have been studying it for years and still continue to debate its merits. Here is a summary of the best arguments for and against a ban on fracking.

The best case against a ban: Fracking has reduced greenhouse gas emissions and helped expand clean energy

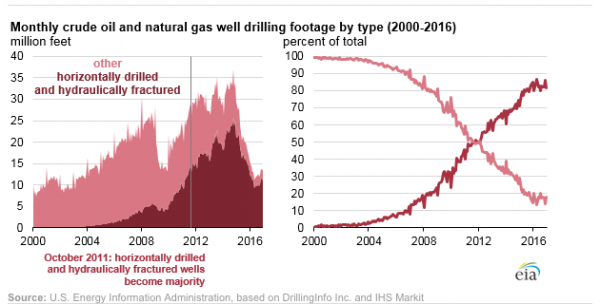

Though hydraulic fracturing as a technique has been around since the 19th century and the first commercial fracking for gas took place in the 1940s, the most recent fracking boom started in earnest around 2005. That’s when the rising prices of oil and gas forced energy companies to look for other sources, when related techniques like horizontal drilling and low-cost slickwater fracking matured, and new estimates revealed the gargantuan amounts of gas stored in formations like Marcellus Shale.

Fracking has now become the dominant technique for extracting oil and gas in the US.

Fracking has risen against the backdrop of the United States’ massive carbon footprint. The US is responsible for the highest share of cumulative global greenhouse gas emissions of any county. Currently, it’s the second-largest emitter in the world, behind China. It also has some of the highest per capita emissions in the world.

Scientists have warned that if humanity wants to limit warming this century to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, countries would need to halve global emissions by as soon as 2030 and reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

During much of the fracking boom, the US economy grew and emissions declined. One study found that between 2005 and 2012, fracking created 725,000 jobs in the industry, not counting related supporting jobs. “This has been one of the most dynamic parts of the U.S. economy — you’re talking about millions of jobs,” Daniel Yergin, vice chairman of IHS Markit and founder of IHS Cambridge Energy Research Associates told CNBC.

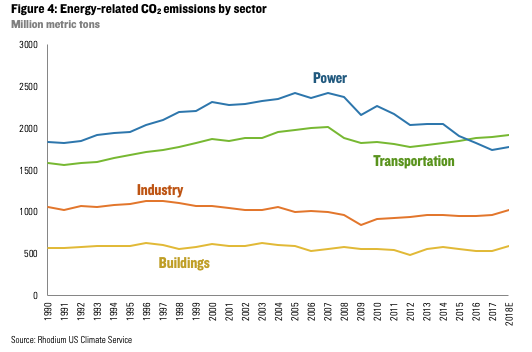

That’s largely due to natural gas from fracking displacing coal in electricity production. Natural gas emits about half of the greenhouse gas emissions of coal per unit of energy. It doesn’t have the massive land footprint that open pit mining or mountaintop removal coal mines do. While it has its own pollution problems, burning natural gas doesn’t produce pollutants like ash and mercury, which can pose health and environmental hazards for years.

“Regardless of what you believe about the future, shale gas has played a substantial role in getting rid of carbon emissions and conventional emissions from coal,” said Ori.

A 2013 report from the Breakthrough Institute titled “Coal Killer” explained that coal-fired power generation declined from producing 50 percent of US electricity in 2007 to 37 percent in 2012. Natural gas from fracking largely rose to fill that void.

The main reason for this shift is that fracked natural gas is cheaper than coal for the energy it produces. That makes it attractive for utilities, especially in competitive markets. Many natural gas power plants use combined-cycle gas turbines. Not only do they produce 50 percent more energy for the same amount of fuel compared to a single-cycle turbine, they can spool up quickly to meet surges in demand or shortfalls from other power producers. Compared to coal and nuclear power plants that have a harder time ramping up and down, this added flexibility makes natural gas power plants particularly valuable on the grid.

Even the newest, cleanest, more efficient coal-fired power plants struggle to compete with natural gas.

Natural gas’s flexibility has also eased the integration of variable renewable energy sources like wind and solar power. When the breezes slow down and clouds form above, natural gas steps in. This has reduced the need for other ways to compensate for intermittency, like energy storage.

In fact, as fracking has grown in the US, renewable energy generation has doubled since 2008. Renewables, including hydropower and biomass, now comprise just over 17 percent of total US electricity generation. Coupled with nuclear power, about 19 percent of the electricity mix, that still leaves nearly two-thirds of power generation that needs to decarbonize. And that will take years.

So fracked natural gas’s record as a coal slayer and renewable energy booster makes it a valuable weapon in the fight against climate change.

“If you’re talking about natural gas as a decarbonizing fuel while replacing coal, I think the facts on the ground really support that,” said Alex Trembath, a coauthor of the “Coal Killer” report and deputy director at the Breakthrough Institute. “We’ve actually seen significant growth in solar and wind in particular even alongside the fracking revolution.”

At the same time, fracking has helped insulate the US from global economic shocks, particularly in oil markets. US shale oil has provided more than half the growth in global oil supplies, so rising tensions and disruptions in countries like Iran, Libya, and Venezuela have barely moved the needle at the gas pump.

“The oil price impacts of those big disruptions have been pretty muted and a lot of that has to do with the incredible growth of shale oil as a source of new supply in the global market,” Ori said.

In short, natural gas obtained by fracking has reduced emissions, aided the economy, and helped clean energy rise, while costing less than dirtier fuels.

The best case for a ban: Fracking keeps us dependent on fossil fuels and undermines decarbonization

Both the oil and natural gas produced from fracking have their downsides. Natural gas is mainly used for power generation (it’s now the largest source of electricity in the US) while oil is mostly used for transportation, like cars, shipping, and aviation.

So while low natural gas prices have helped knock dirty coal off the market, low oil prices driven in part by fracking have encouraged more travel. In fact, transportation is now the largest source of greenhouse gases in the US. And after years of decline, US emissions in 2018 rose by 3.4 percent.

Low oil prices have undermined the business case for cleaner transportation alternatives, like electric cars and fuel cell-powered buses. Instead, the United States has experienced a growing appetite for larger, thirstier cars and more air travel.

Meanwhile, low natural gas prices have had some collateral damage for nuclear power, the largest source of clean electricity in the US. Some of the nuclear power plants that have announced early retirements are likely to see their capacity replaced by natural gas. So while replacing coal with natural gas often leads to a reduction in emissions, replacing nuclear leads to an increase.

Natural gas itself can also become a climate problem. Methane, the dominant component of natural gas, produces less carbon dioxide than coal when burned. But if methane leaks, which it often does in some quantity during normal gas extraction operations, it becomes a potent greenhouse gas. Over 100 years, a quantity of methane traps more than 25 times the amount of heat compared to a similar amount of carbon dioxide.

Of course, methane is the product, so the gas industry has an incentive to limit leaks. But leaks are difficult to track, and they could easily overwhelm the gains from replacing coal.

Robert Howarth, a researcher studying shale gas at Cornell University, recently reported that US shale gas production plays an outsized role in global methane emissions. He estimated that over the past 10 years, more than half of the global increase in methane emissions came from fracking in the US.

“Natural gas production in the United States is leaking somewhere in the neighborhood of 3.5 percent of the gas we produce into the atmosphere which is, you know a relatively small amount of gas if you think about it. Most of it is getting to market,” Howarth said. “But that 3.5 percent is enough to do severe damage to the climate.”

This is a higher leakage estimate than what the EPA and the industry calculate, but with the Trump administration’s ongoing rollbacks on Obama-era regulations on monitoring and restricting fugitive emissions of methane, the problem is poised to worsen.

And then there’s the technique of fracking itself. It requires a massive volume of water. Wells can release toxic chemicals like benzene into the air. Fracking sites can experience explosions and fires. They can contaminate drinking water. More than 17 million people in the US live within a mile of an active fracking well and research shows that fracking can lead to low birth weight in infants born in that radius.

Many of these environmental risks, on balance, are less than those associated with mining and burning coal. However, the sudden surge in fracking means that many people are being confronted with its impacts for the first time, making it a more vivid political concern. That’s in contrast to coal hazards, which are mostly grandfathered into the public consciousness.

Another factor is that the business case for fracking is starting to weaken as more drillers declare bankruptcy. The Rocky Mountain Institute estimates that clean energy is already competitive with new natural gas power plants, and by 2035, it will be cheaper to build new wind, solar, and storage projects than to continue running 90 percent of existing gas power plants.

And when it comes to limiting climate change, a key factor is time. Methane leaked from gas wells can stay in the atmosphere for a decade. Carbon dioxide from burning it can linger for a century. So it is imperative to ramp down greenhouse gas emissions as quickly as possible. Yet every new natural gas power plant represents a decades-long commitment to continue using the fuel. That means gas plants will have to install carbon capture systems, which would add to their operating costs and worsen the business case further, or some poor investor is going to be left holding the bag.

“Not only is natural gas dangerous and destructive, it’s increasingly unnecessary,” said Michael Brune, executive director of the Sierra Club. “We do think there should be a national ban on fracking.”

What can a president actually do about fracking?

President Obama often boasted about the rise of the United States as an energy producer. President Trump has pushed to leverage US oil and gas in order to exert energy dominance. But it’s clear that the era of bipartisan support for fracking at the national level has come to an end.

Now some Democrats are openly hostile to the fossil fuel industry, with Sen. Bernie Sanders calling for criminal prosecution of some companies. Democratic presidential candidates were asked about their stance on fracking during the CNN climate town hall, and they will likely continue facing questions throughout the campaign.

Former Housing and Urban Development Secretary Julián Castro said during the town hall that his past support of fracking came from a belief that natural gas would serve as a bridge fuel, “but we’re already coming to the end of that bridge.”

The federal government can limit export licenses for oil and natural gas. However, a lot of the energy policy in the United States is governed at the state and local level, so a president can’t easily shape the agenda without local backing.

While several candidates like Sen. Elizabeth Warren have proposed ending all new leases for fossil fuels on public lands, the vast majority of fracking takes place on private land. That means further restrictions on fracking would require legislation.

IHS Markit’s Yergin was critical of Warren’s fracking proposal. “In the US, oil production is primarily regulated by the states but there is so much that the federal government can do with a thousand cuts of regulation and so forth,” told CNBC. “And to just say she’s against fracking shows a total lack of understanding.”

At the local level, despite environmental and safety concerns, voters have been reluctant to restrict fracking. A ballot measure that would have severely restricted fracking in Colorado failed last year, despite Democrats winning the governorship and majorities in both state houses.

Breakthrough’s Trembath argued that a president would best be served by building an off-ramp for the bridge rather than cutting it off. It would be less disruptive and contentious and would allow the country to continue harnessing the benefits of fracking while coming up with better options.

“The first way we hasten the end of the bridge is to make the [alternative] technology cheaper,” he said.

That would require investment in clean energy research and development, particularly for technologies like long-duration energy storage and advanced nuclear. Pricing carbon dioxide would also help ensure that the biggest sources of greenhouse gases get reduced first, and the revenue these prices generate could fund further research. These are tactics that almost every 2020 Democratic contender supports.

So it’s worth asking presidential contenders not just whether fracking should continue, but how they intend to transition the country off a technology that has made such a massive impression across the economy.

Sourse: vox.com