US public transportation is notoriously underdeveloped compared to most other wealthy countries. In fact, according to a recent study, the New York City subway is the only US rail system that ranks among the 10 busiest in the world.

Another report found that transit ridership fell in 31 of 35 major metropolitan areas last year, including in Washington, DC, Chicago, and New York City. However, 2018 has birthed some new transit projects, including a high-speed rail line from New Haven to Hartford, Connecticut, and the TEXRail, which will travel from downtown Fort Worth to DFW Airport.

Christof Spieler, a structural engineer and urban planner from Houston, has lots of opinions about public transit in America and elsewhere. In his new book, Trains, Buses, People: An Opinionated Atlas of US Transit, he maps out 47 metro areas that have rail transit or bus rapid transit, ranks the best and worst systems, and offers advice on how to build better networks. I recently spoke to him by phone about what cities are doing right and wrong in investing in public transit, and what they should focus on for future projects.

Which cities have good service?

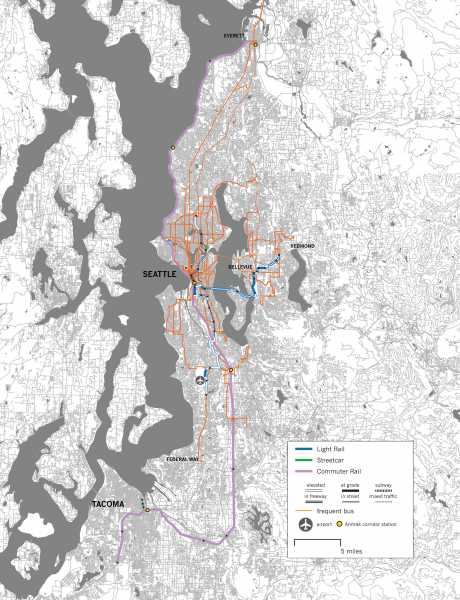

Seattle is doing a really good job of both expanding its rail system and improving its bus system at the same time, and actually linking the two systems together to make a much more useful system overall. And not coincidentally, it’s one of the few US cities where transit ridership is growing.

One of the things I found very interesting is there are some smaller cities that are doing a very good job of building transit networks and, in many cases, are actually more impressive than in larger cities. Richmond, Virginia, just redesigned their bus network and built a new BRT [bus rapid transit] to go along with it. I think it’s a really smart implementation. The bus rapid transit in Hartford, Connecticut, is a really good network.

I’m also generally very impressed with the Twin Cities [Minneapolis and St. Paul], which is another case of a really good bus network including some new routes — like the A Line which I think is probably one of the best bus routes in the country, just in terms of how good the passenger experience of riding the bus is. That links very well with two rail lines that connect at exactly the right places that really connect a lot of major centers together.

Even when there’s bad weather?

I’ve actually heard a presentation from their team on how the Twin Cities handles snow days, and they are organized about it. They have a special operating plan for blizzard coverage where certain routes operate and certain routes don’t. Despite the weather, they actually figure it out quite well.

I think something that you also notice is that operating cultures are very different. When I talk to transit people in the Twin Cities, they take a lot of pride in operating their system well. Whereas I think there are other systems where their reaction to weather is, “It’s not our fault, don’t blame us.” In the actual passenger experience of transit, the culture of the agencies can make a lot of difference.

What are small cities implementing that is so impressive?

Technically it’s buses, but what they have in common is their bus rapid transit line. Those buses have their own lanes, they have stations that resemble train stations. One pattern in all these cities is that they are integrating multiple lines together.

Successful transit networks aren’t a series of individual routes; they are a network made up of multiple routes. One of the problems with how we talk about transit is that we often talk about it one route at a time, and that’s not how good transit systems work. You’re adding a route to other routes that makes the whole system more useful. And that’s really a pattern in the cities that I’ve seen to be successful: They think about their entire networks, not just one route.

What city is doing it wrong?

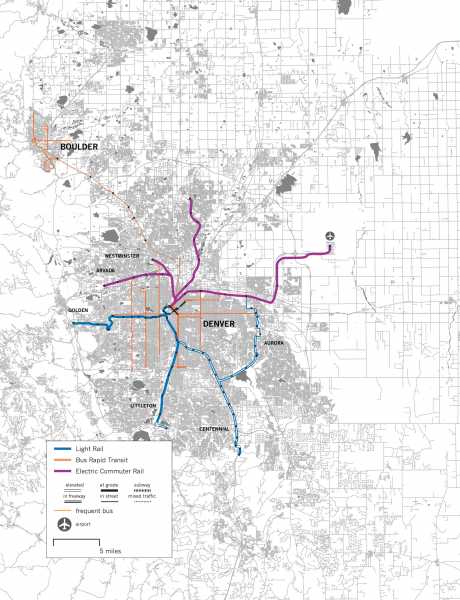

I think one city, for example, is Denver, which has built a huge amount of transit, but in the process of building a huge amount of transit, they haven’t actually reached a lot of the places where people want to go. If you look at the busiest transit route in Denver, I believe it is not actually one of the rail lines, it’s the Colfax bus running on city streets in mixed traffic. Whereas places with much lower ridership get full light rail. So I think if you look at where the resources have gone compared to where the demand is, it doesn’t fit very well.

We’ve also seen some cities invest in streetcar lines that really don’t do a lot of good. I think Cincinnati is a really good example of that. It’s a city that has four major activity centers lined up in a straight row, a really strong natural transit corridor, and they built a streetcar that connects exactly one of the four. That has a lot to do with limited resources and politics and everything else, but the result of that is adding a new line that doesn’t make the system more useful.

Why do you think cities slap together these lines that aren’t as useful?

I think there’s a couple of reasons. First of all, I think we tend to talk too much about technology. There’s too much focus of bus versus trains. And we often think of technology as an end to itself.

A lot of cities say things like, “This city needs light rail,” or, “This city needs a streetcar,” which is a really bad way to start a transit discussion. I think a transit systems should start with, “We have this corridor connecting these place together and we want an improved transit line in that area.” Instead, a lot of cities come to it from a standpoint of, “Well, we want to build a rail line.”

I think there’s a tendency to focus too much on longer regional trips when the strongest transit markets are often in the denser core. You’ll see San Francisco has been investing a huge amount of money into long suburban rail extensions to very low-density areas where they simply aren’t getting a lot of ridership because there aren’t a lot of people there, but those lines look impressive on a map. If you draw a map of the whole region, those look like they’re doing a lot. And they also respond to political jurisdictions where you see a lot of pull.

“San Francisco has been investing a huge amount of money into long suburban rail extensions to very low-density areas”

I think there’s also a very strong tendency to avoid places where design or politics are difficult. So there’s a lot of different systems that put transit along freight rail lines or freeway corridors because it’s easier, because the space is there, because there will be less opposition, but those are not the places where people are.

For transit to be useful, it has to be within walking distance of the places people are actually going. And the destination where people are actually going are is not in the middle of the freeway. They tend not to be along those freight rail line either because those tend to be surrounded by warehouse and industrial areas, not activity centers or residential areas. So a lot of cities build transit where it is easy rather than where it is needed.

Why do you think people like to say that their city has bad public transit?

One thing that’s funny is when people say, “City X has no public transit,” what they actually mean often is it has no rail line, which is a very different thing. A good bus route is good transit. So when I mapped in the book, I made a point of mapping not just rail lines but mapping frequent bus routes as well because those are a really important part of the system.

I think the second, complaining is kind of part of our relationship with transportation. I have yet run into a city where people have no complaints about their transit system. And, in fact, sometimes the places where you hear the most complaints are the best systems because the fact that people are complaining about it is a sign that it actually matters to them. [In] places that only have very small, low-frequency bus networks, people don’t tend to complain much about transit since they don’t think about using it.

Some of the most [frequent] complaints about transit are Chicago, Boston, and New York, and it’s partially because those system actually serve a lot of people.

I would also say, in the United States compared to the rest of the world, we’re not doing very well. If you look at even cities like New York or Boston or Chicago, those are huge international cities, the absolute center of the US economy, and we’re underinvesting in transit pretty dramatically. In New York, we’re talking about a major lift just to keep the subway as it is operating. When you look at cities like London or Paris, they are actually building major new lines on top of their existing network. The most ambitious plans in New York pale in comparison to what its competitors around the world are doing.

“Sometimes the places where you hear the most complaints are the best systems”

So I think when people are complaining about transit, in many cases, they are right. In many cases, the resources aren’t there. And it’s not just money. It’s also things like being willing to say, “This is a really busy bus route down a congested street; we will give it its own lane.” Being okay with saying there will be no parking on this street or there will be one less lane of cars because actually the buses carry more people than anything on this street. And very few cities are actually willing to make decisions like that. So I think people’s complaining about transit in many ways is accurate.

What is Paris, for instance, doing that the US isn’t?

They converted their commuter rail network into an all-day, seven-day-a-week service rather than lines that are only targeted at 9-to-5 commuters. In doing that, they also dug whole new tunnels under the city and actually transformed commuter rail network into a true regional rail network, which no city in the US has done.

Even in New York, northern New Jersey is one of the densest places in the US with very poor transit service, very little frequent service. Its buses come every half-hour, maybe. And it has, right in the core of those areas, some very high-quality rail infrastructure with very low-quality service. Like, a train every hour, and there’s enough demand there to fill a train every 10 to 15 minutes all day if it really was integrated as part of the transit network rather that treated solely as an express service to New York City.

Paris has also taken some major amounts of street space in the city center to install some really high-quality tram rail lines that are carrying a lot of people. And they are building new subway lines through the heart of Paris and connecting to some of the outlying neighborhoods. [It’s] a huge investment on the scale that a US city has not really contemplated. And they’re doing all that at the same time.

Is it cheaper over there, or do they have more money?

Both. We could do a lot better if we focused on how could we do this more cost-effectively. But it’s also just very much allocation of resources. And if you look at how much money is being put into highway expansion and compare that to what’s being spent on transit, even in places where transit bears a bigger load that highways do, it’s pretty remarkable.

Are there any cities that will never embrace public transit?

I would say in any decently sized metropolitan area, there are already bus routes, at least, that are carrying people who very much depend on that service. I also think there are many more people who would greatly benefit from having access to service like that.

There are a lot of people who are being forced to own cars even though they really can’t afford that. And who are paying major financial and emotional consequences as a result of that, where they are literally scrimping on food for their kids so they can afford to have a car because there is no way they can get to work without it. And if there was a better transit system in place, they would be in much better shape. So I think that need for transit exists everywhere.

What about sprawling cities like Los Angeles?

There are a lot of people riding transit in Los Angeles; it’s definitely not New York or Chicago, but there are bus routes and rail lines that are standing lonely every day in Los Angeles. And I think it’s really useful to tease this apart because when we say Los Angeles, we’re thinking of this entire sprawling metro area.

There are parts of that, large cul de sac areas somewhere in the Inland Empire where I don’t think transit will ever be a particularly convenient way to get around. But there’s other large parts of Los Angeles that are quite dense, where if you put a bus line there, there are lots of people who live in walking distance.

The Expo Line from downtown LA to Santa Monica has exceeded its ridership expectation. It turns out there are a lot of people who want to make that trip, and that rail line is a very convenient way to do it.

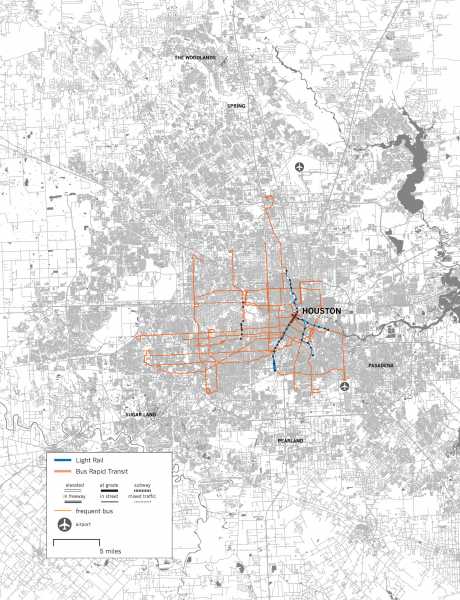

A blanket statement that “this metropolitan area isn’t suited for transit” usually isn’t true. That’s something that we’ve found in Houston, which is definitely a car-oriented city, a post-World War II city that is largely built around making cars convenient. Yet when Houston opened its first light rail line, it got more riders per mile than any other city outside of Boston and San Francisco, because it went through dense areas and connected major activity centers together and connected to the bus system.

What do you think of the future of transportation as it pertain to technology?

In general, we get too excited by technology. In some cases, technology really is a change, but it doesn’t make a difference to the fundamentals of what works and what doesn’t. Micro-transit [on-demand public transportation by small and/or private cars] is fundamentally a dial-a-ride service, which has existed a long time.

Yes, it’s more convenient if you order it from an app than if you call it from a phone, but fundamentally, it is the same technology and has the same limitations: It can never carry large numbers of people.

Transit uses space incredibly efficiently. Whether it’s a bus or train, the amount of people it can move in a specific amount of street space far exceeds what cars can do. And that allows density, that allows cities to function. If you think of Manhattan, it could never function without transit. It could never function with only single-occupant vehicles. And I don’t think autonomous vehicles or any app undoes that.

So you think transportation departments should focus on traditional infrastructure?

Transit agencies across the country should focus on what transit is good at: basic infrastructure and high ridership service that will benefit lot of people. At the same time, there are still lots of good reasons to have that lower-frequency coverage service that serves the areas that don’t have high ridership demand, and I absolutely think it’s worth looking at new technologies to do that.

But I think the discussion should always start with the definition of what you’re trying to accomplish rather than what the technology is.

You should start with saying, “This is the kind of service we want to provide,” and see what technology can do that, rather than start by saying, “Here, we have this new technology, what could it be good for?” The technology isn’t the goal; it’s the service.

Sourse: vox.com