toy market, one wooden block at a time” alt=”How Melissa & Doug captured the toy market, one wooden block at a time” />

toy market, one wooden block at a time” alt=”How Melissa & Doug captured the toy market, one wooden block at a time” />

How Melissa & Doug captured the toy market, one wooden block at a time

The rise of tech could have been the company’s downfall. Instead, it’s been a boon.

By

Chavie Lieber@ChavieLieber

Dec 7, 2018, 2:30pm EST

Share

Tweet

Share

Share

How Melissa & Doug captured the toy market, one wooden block at a time

tweet

share

Earlier this fall, just ahead of the holiday season, Amazon mailed a catalog of its best-selling toys to some 20 million customers. The colorful booklet was filled with the usual suspects: Mattel’s Barbie and Hotwheels, Hasbro’s Play-Doh and Monopoly, plenty of Lego sets. There were lots of toys from Hollywood franchises, too — The Incredibles, The Avengers, Harry Potter. In typical Amazon fashion, the catalog also featured tech and gadgets, like its own Echo Dot Kids smart speaker and items from Bose, Xbox, PlayStation, and Nintendo.

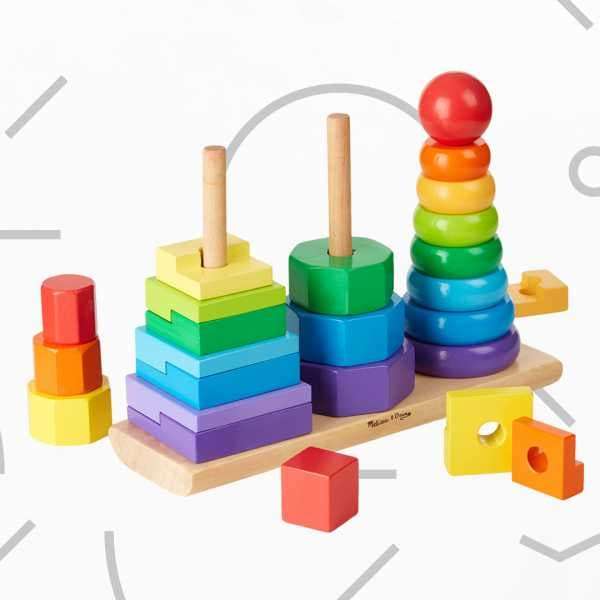

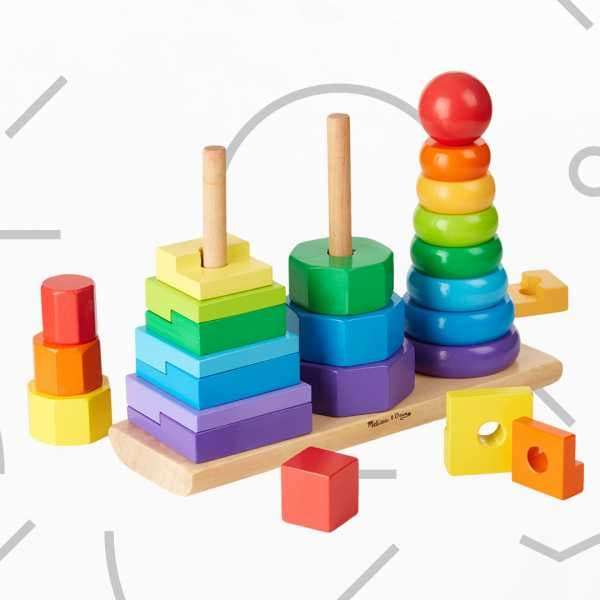

Peppered in among all these super-commercial products was a different kind of Amazon best-seller: simple, colorful, wooden toys. There was a train made of stackable blocks for pretend traveling, an ice cream parlor set with mix-and-match scoops and cones for pretend eating, and a mini broom and mop for pretend cleaning.

These toys were all made by Melissa & Doug, a 30-year-old American toy brand. Independently owned and operated by husband-and-wife team Melissa and Doug Bernstein, the company makes products that don’t require batteries, or make automated sounds, or produce flashing lights. Instead, the toys stack, crinkle, push, pull, and spin. The company focuses on imaginative play that mimics real life, via wooden vehicles and play-food sets.

Since the early days of the Bernsteins’ business, those in the toy industry told them they’d fail if their products didn’t keep up with the times. Tech is the future, they’d say, but Melissa & Doug was, and still is, inspired by the past.

In an era when children are bombarded with screens and all manners of tech, the company has maintained its spot in the crowded toy market despite the fact that — and perhaps because — the company’s toys have no electronic components to them. Melissa & Doug is set on making toys that are meant to be timeless, in an effort to preserve a cornerstone of childhood that the founders believe is under attack: open-ended play.

The Melissa & Doug headquarters is located off a busy road in Wilton, Connecticut, tucked behind a cluster of tall trees. The office has cheerful carpeting and walls covered with colorful pages from toy catalogs. There are whole cubicles dedicated to displaying mini wooden supermarkets, hospitals, and diners. Every corner of the office is jammed with products.

While Melissa & Doug is best known for its wooden toys, they only account for about 40 percent of the company’s lo-fi merchandise. The rest are made of fabric (like the giant stuffed animals from its plush toy collection), cardboard (like its beloved nesting blocks), and sometimes a little plastic (like its playmats or barn animals).

A showroom at the Connecticut office houses many of the company’s 2,000 items that are currently in production, from costumes to coloring books to dollhouses to instruments to all those wooden toys. A corner of the space is a toy graveyard, dedicated to discontinued products that never quite made it, which the company likes to keep in sight for inspiration and ideas.

The entire office could easily be mistaken for a giant kindergarten classroom, a feeling that’s only amplified by Melissa Bernstein’s serious kindergarten teacher vibes. The 56-year-old mother of six is petite with a giant smile, a soft voice, and an enthusiastic way of talking with her hands. Melissa is the queen of the Melissa & Doug enterprise, coming up with the ideas for her toy kingdom as the company’s creative director, while her team of 30 executes on them. Doug, who is just as jovial as his wife, is the company’s CEO and runs the business side of the brand, which is carried in 15,000 stores.

Both Melissa and Doug were raised by child educators, and their parents set them up in 1985. Three years into their relationship, while Melissa was attending college at Duke and Doug was working at a marketing firm, the couple decided to start a children’s business together. Their first venture was a production company that made fun educational videos for kids. While they struggled to get their tapes stocked by retailers, they brainstormed about other kids’ merchandise they could sell.

“Our aha moment was going to stores and seeing that something as fun as puzzles were dull, boring, and had no pizzaz,” Melissa says. “They were just flat, with no texture. We started thinking about our childhoods, and recalled that our favorite book was Pat the Bunny because it was so interactive. We thought we could make toys better.”

Their first product, a “fuzzy puzzle,” featured farm animal cutouts made of thick wood and topped with fur. It was an instant hit in small specialty shops, and so the pair ditched their videos, which had landed in a few stores but hadn’t gained much traction. Melissa & Doug stuck to puzzles for another decade before expanding into other wooden toys, many of which are still best-sellers today, like the Pounding Bench, which has colorful pegs you bang on with a mallet.

The Bernsteins chose wood as their primary material because it evoked classic children’s toys like dollhouses, blocks, wheelbarrows, and rocking horses. Toys were mostly made of wood and steel until after World War II, when a post-war housing boom meant these materials were hard to obtain, according to the American trade group the Toy Association.

Fisher-Price the one of the first toy companies to introduce plastic into its assortment in 1950, and the debut of products like Mattel’s Barbie in 1959 and Hasbro’s GI Joe in 1963 officially made plastic a more popular toy material than wood. Even Lego used to be a wooden toy manufacturer; the Danish company was started by carpenters who made wooden animals and trucks. It wasn’t until 1953 that it started making interlocking plastic blocks.

Melissa & Doug wasn’t known in the mass toy market until 1999, when the now-defunct chain Toys R Us bought educational toy company Imaginarium, which stocked Melissa & Doug. That year, the company also inked a deal with Amazon, which was then a popular internet bookseller about to expand into toys.

Doug sent his brother Brian to Seattle to establish a connection with Amazon, and the e-commerce company agreed to stock Melissa & Doug as one of its first toy brands. (Amazon simultaneously signed an agreement to make Toys R Us its exclusive toy vendor, a deal that Amazon violated by bringing on Melissa & Doug and several other vendors, resulting in a 2004 lawsuit between the two retail giants.)

Doug attributes much of the company’s success to Amazon: “It gave us incredible accessibility and was a major facilitator of growth. It helped us generate over 100,000 organic toy reviews early on and got the flywheel going. Getting on Amazon early is probably the reason why our older toys still sell really well.”

During the early aughts, even as the company soared, many warned Melissa & Doug that it was headed toward failure. Doug recalls attending a big trade show and being told, “It’s been really nice knowing you, but everyone is getting into tech. Unless you guys start making electronic toys too, you’re going to go bankrupt.” Melissa says toy stores begged the company to consider integrating licensed characters.

On both fronts, the Bernsteins refused. These moves, they believed, would be at odds with their philosophy of open-ended play — that is, minimally structured free time without rules or goals. The American Pediatric Association considers this kind of play crucial for a child’s development, particularly in terms of imagination and creativity. Studies have shown that simple toys are better for open-ended play than complicated ones, since they’re more imagination-igniting.

Television and movie characters, for example, already have names and personalities attributed to them, and so toys featuring these characters dictate how kids play with them; conversely, straightforward items like blocks or paint better promote creative thought.

Wooden toys have long been associated with open play and are a favorite of educators, particularly those who ascribe to the Montessori and Waldorf philosophies. The Montessori philosophy states that wooden toys “emphasize simplicity, setting children up to be able to learn things on their own through their own explorations”; Waldorf educators prefers toys made of “natural materials” like wood because it is “nourishing to a young child’s senses,” as one teacher puts it.

(Although Melissa & Doug had no formal connection to either Montessori or Waldorf, both the company and these school movements saw major expansion in the ’90s and ’00s).

Today Melissa & Doug is one of the largest toy companies in the country, behind Hasbro, Mattel, Hallmark (which owns Crayola), and Spin Master (the company behind Hatchimals and owner of the Paw Patrol IP). Though it was self-financed for years, it accepted an undisclosed amount of funding from Boston private equity firm Berkshire Partners in 2010 to sell its products internationally. Reports have claimed the company sells more than $400 million worth of toys annually; though the company declined to share sales figures with Vox, a rep said the actual number is higher.

Melissa & Doug’s sales may seem like peanuts compared to Hasbro’s $5.2 billion or Mattel’s $4.8 billion, but the company has been able to compete alongside these corporate giants. Each year, Melissa & Doug introduces about 200 new toys, while retiring around two-dozen underperforming ones.

Its products are affordable, but not exactly cheap. Play food sets and wooden stacking blocks cost around $20, which is more than double what a brand like Fisher-Price charges for similar products. The price adds to the premium appeal of the toys, which are all made in China and Taiwan.

“Parents gravitate to Melissa & Doug toys because there’s a high-end quality and aesthetic to them,” says Rachel Blumenthal, the founder of kids’ clothing subscription box, Rockets of Awesome, and mother of two. “There’s no parent that likes toys that make annoying sounds, and when you’re gifted one, they feel really downmarket. But there’s something really sophisticated and elevated about wooden toys.”

Still, the cost can be hard to swallow. “So stink’n expensive,” one parent lamented on the Bump. “A mom had this [toy] at a playdate and I thought it was great until I saw the price!” Amazon reviewers have also called the company’s toys overpriced, and noted that they aren’t worth the investment since children tend to “lose everything.”

Melissa & Doug’s toys are a favorite of millennial parents willing and able to pay not only for quality, but virtue in what they buy their kids. The same cohort obsessed with toxins and “clean beauty” also wants to pamper their babies with all-natural diaper creams and organic baby food. These parents opt for wooden toys because they believe the toys are better for their babies’ brains, and also the environment.

And unlike plastic toys, wooden toys don’t come with risk of BPA exposure, though Melissa & Doug did have to recall more than 26,000 toys in 2009 because of lead paint contamination. It also helps that the toys are nice to look at, an extra boon for the Instagram-obsessed.

“I love the toys because they are realistic-looking and imaginative for kids to play with, but are also aesthetically appealing,” says Jodi Popowitz, a mom and interior designer living in New York City. “When designing nurseries, I use them for decorating because they’re the perfect toys to go on a bookshelf. I do find that some of the toys are even more appealing to the eye than easy for kids to play with.”

In August 2018, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) made an unprecedented ruling, recommending that pediatricians start writing prescriptions for open-ended play.

David Hill, an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine and a program director with the AAP, says the move was born out of concern that kids’ days are being crammed with school and extracurricular activities, leaving little room for unstructured time spent exploring backyards and building towers in living rooms. The recommendation was also given because technology is endangering play, one of the basic pillars of childhood.

Kids ages 8 to 12 spend an average of four hours and 38 minutes on screens a day, while children 8 and under average two hours and 19 minutes, according to the safe technology nonprofit Common Sense Media. The AAP warns that the overuse of screens puts children at risk of sleep deprivation and obesity, and although it’s still too early to determine the exact effects screens have on children, there are researchers attempting to glean some preliminary insights.

Dr. Dimitri Christakis, a pediatrician at Seattle Children’s Hospital and head of its childhood development lab, has studied mice exposed to high stimulation from lights. He found that their cognitive abilities suffered tremendously, and believes this research can be applied to young children exposed to screens. A study commissioned by the National Institutes of Health, meanwhile, found that limiting screen time improves kids’ brain function and academic performance.

Josh Golin, the executive director of the nonprofit Campaign for a Commercial Free Childhood, notes that in a bid to compete with Big Tech, and in order to stay relevant amid the rise of screen time, toy companies are making products that replicate the screen experience.

Target, for example, sells a pared-down VTech smartphone for children as young as 4 that has a camera and allows kids to access the web, while Fisher-Price makes an iPhone-like gadget that teaches babies as young as 6 months how to activate a toy by swiping to unlock it.

Then there are products that encourage parents to integrate technology into otherwise mundane baby products, like the child’s potty sold by BuyBuyBaby that features an attachment for a tablet. Fisher-Price is perhaps the worst offender, selling a toy that features colorful rings for teething, and also a slot to insert a smartphone. In 2013, Fisher-Price made an infant bouncy seat that allowed parents to snap in an iPad that would hover over the baby (the product has since been discontinued). The company also has an entire line of iPhone-enabled smart teddy bears.

Hill finds these products problematic because, he says, toys should do as little as possible.

“Playing should be an outlet for creativity and expression, and it isn’t just for fun — it’s developmentally important,” Hill says. “The rolling cars, the stacking blocks; these things suit developmental needs in ways that electronic goods do not. That toy kitchen set or that fireman’s hat allows kids to occupy an imaginative environment that will take them to a new world. They have negotiations in this world, they learn to share, they imagine responses, and try on different identities. These are acquired skills through practice, and they don’t happen when buttons are pressed and there’s instant entertainment at kids’ fingertips.”

And so medical professionals like Hill are telling parents to buy simpler toys from brands like Melissa & Doug. In an AAP report titled “Selecting Appropriate Toys for Young Children in the Digital Era” that came out just last week, the medical organization recommended parents avoid electronic toys because “evidence suggests that core elements of such toys (eg, lights and sounds emanating from a robot) detract from social engagement that might otherwise take place through facial expressions, gestures, and vocalizations.”

Hill notes that while the AAP wants to give parents who aren’t as educated on the potential harms of technology an extra push through these recommendations, this type of messaging is in lines with what many parents are being told by their kids’ teachers.

“Melissa & Doug’s success shows that there still is, maybe now more than ever, a thirst to go back to classic toys that don’t have any of the noise or flashy tech,” says Golin. “The difference in their prices compared to other toy brands is striking, though, and it’s unfortunate that there’s such a socioeconomic divide on this. There should be good toys that are affordable to families of all incomes.”

Part of the CCFC’s work as a watchdog organization is to call out false claims within the toy industry. Golin says the group constantly encounters companies making inaccurate claims about their products’ educational benefits. Apps for children as young as 6 are marketed as educational, and yet a study from the University of Michigan and the C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital in Ann Arbor found that almost all of them are filled with ads to buy game add-ons that keep the kids playing longer, luring young users into spending money under the guise of education.

“Today, everyone claims their toys are educational, but most of these companies aren’t doing research with child development specialists,” says Golin. “It’s a very confusing time to be a parent shopping for toys because ‘educational’ has no meaning today.”

Melissa & Doug can’t promise it will make your kid a genius, but its wooden fruits sets are a better way to promote the open-play

Hill acknowledges that some computer games can serve as a “virtual playground,” helping kids with team-building, though he maintains “there are certain aspects of play that can’t be duplicated on a screen or with a gadget.”

“Children,” Hill says, “need to learn about the physical world and how to interact with it on their own. They need laps, not apps.”

Then there are the issues of privacy and surveillance inherent in tech, which get even more concerning when children are involved. Last year, a team of British researchers at Pen Test Partners found that the smart toy Teksta Toucan could spy on children. The toy is Bluetooth-enabled and can connect to internet devices; its speaker and microphone allow the toy to listen and speak to children, but were not built with security in mind and were susceptible to hacking. This same research group found similar vulnerabilities with the Bluetooth-enabled smart doll My Friend Cayla.

Those Fisher-Price smart teddy bears have been the target of similar safety concerns, as has Mattel’s wifi-powered Hello Barbie and Hasbro’s Furby Connect doll. Last year, the smart toy brand CloudPets was exposed for storing millions of children’s voice recordings and photos, data which was compromised by hackers (the toys have since been pulled from eBay and Amazon).

The FBI even issued a warning last summer for parents to pay close attention to internet-connected toys being brought into their homes, since they come with so many security concerns. These instances further incentivize parents to look for tech-less toys.

Although the Bernsteins say they prefer to stay out of the spotlight, the couple has become outspoken figures against technology and for open-ended play.

“I’m an introvert, and I create with my hands, not my words, but I’ve had to become more vocal about this because I’m fearful for this generation of kids,” says Melissa. On the Melissa & Doug blog, she writes about the importance of “taking back childhood” from technology and the plethora of extracurricular activities she believes “robs a child from discovering who they are.”

She’s made bold statements about how kids shouldn’t have screen time until they are 6 years old (the AAP’s recommendation is for screen time to be avoided until children are 18 months) and published essays about how overparenting and overscheduling is ruining kids’ imaginations. She speaks at conferences and on Facebook Live about the need for children to scale back on screen time and hobbies and just play.

The company is also pushing back against technology by commissioning studies about tech’s effect on children. Last year, it partnered with Gallup to study how children are lacking open-ended play time in their homes; there will be more studies to come next year, say the founders.

“I think we will look back at this time the same way we now look at the rise of cigarettes,” says Doug. “It took a number of years, but enough research showed the negative impacts of smoking. I’m not a doctor, but we do know that there are negative impacts from a child’s abundant use of technology, and we want to help bring that research forward.”

Doug acknowledges the company is a biased source — if parents aren’t buying electronic toys, they’ll likely turn to Melissa & Doug — but says “we feel we have to stand up and fight, and fight hard.”

Melissa & Doug is also keen on showing parents that the company can stay relevant, and that their kids can remain engaged, in the tech age. Last year, for example, Melissa & Doug debuted a veterinarian kit to keep up with America’s pet obsession; it’s now a best-seller. “Favorite thing in this set is the cone of shame,” one parent wrote on Amazon. “We recently had our dog spayed so the girls have seen this before and knew exactly what to do with it.”

The company recently issued a Slice and Toss Salad set Melissa initially came up with a decade ago for the company’s play food collection. She scrapped the idea at the time, thinking kids wouldn’t want to play with vegetables. But it’s 2018, and salads just so happen to be a booming, venture capital-backed industry now. The Slice and Toss Salad is also a best-seller — parents apparently want wooden greens to match their own trendy salads. “Lettuce, kale, AND spinach!” a parent recently raved.

Not that Melissa & Doug needs to rely too heavily on of-the-moment designs. One of its all-time most popular toys is a set of natural-finished hardwood blocks, perhaps the oldest toy in history. The company wouldn’t want it any other way.

Sourse: vox.com