This story is part of a group of stories called

Uncovering and explaining how our digital world is changing — and changing us.

Sometime in the coming months, iPhone users will start seeing a new question when they use many of the apps on their devices: Do they want the app to follow them around the internet, tracking their behavior?

It’s a simple query, with potentially significant consequences. Apple is trying to single-handedly change the way internet advertising works.

That will affect everyone, from Apple’s giant tech rivals — most notably, Facebook, which announced today that it’s fighting back against Apple’s move — to any developer or publisher that uses ad technology to monitor what their app users are doing on the internet.

Update, September 3, 2020, 1 pm ET: Apple has announced it will delay enforcement of its new rules until “early next year” to give developers and advertisers time to adapt; it remains unclear how this will affect Facebook’s response to Apple’s rules.

And it affects you, the person reading this story. At stake is your online privacy — and the advertising system that underwrites an endless supply of free content.

It’s a fascinating battle because there aren’t clear-cut winners and losers. And multiple players have more than one motivation.

- Apple is in a position to attack intrusive advertising tech because it has consistently argued that it values privacy — and because the company doesn’t have much of an ad business of its own.

- Facebook and other big ad players make billions of dollars tracing the detailed digital footprints their users leave — but they can also argue that ad money they generate allows people to consume news, entertainment, and the rest of the internet for free.

- Meanwhile, ordinary internet users may say they value privacy — but it’s unlikely they have any idea how much personal data they give up when they skim a story or click on a link.

The battle may also generate collateral damage, according to one news publisher, who says Apple’s move will cut into its business at a time when it’s already struggling to hang onto any ad revenue it can find.

“It makes it much harder for us to monetize our Apple app users, who are an incredibly loyal readership. And quite frankly, it puts at risk our ability to provide an Apple app,” says Martin Clarke, publisher of DMG Media, which owns the UK’s Daily Mail and other publications; the company says its MailOnline iOS app attracts 1.2 million users per day. “There’s no point in providing an app for a platform that monetizes less well than other platforms.”

Apple announced its plan in June at its annual developer’s conference. But it hasn’t generated much attention outside of ad tech circles yet.

That will likely change in mid-September when the company is expected to roll out its new operating system, iOS 14. Without getting too far into the weeds, here’s what will happen:

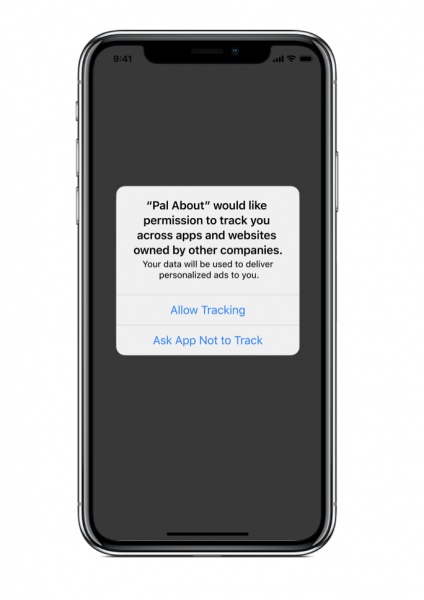

- For years, Apple has given each of its devices a unique identification code that makes it easier to track what you do on your phone. But under its new plan, any developer who wants to use that code — and also wants to use data collected by someone else, or who wants to send to outsiders data its users create — will have to ask you for permission. That will come via an opt-in, pop-up screen that looks like this:

- If a user says yes, then it’s business as usual: App companies and advertisers can combine information they know about a user’s behavior inside of an app, and their behavior on the rest of the web, and deliver highly targeted ads. And users will continue to see the results of their in-app behavior when they use other apps or travel around the web. Like when Zappos follows you around the internet, trying to get you to buy the shoes you looked at briefly.

- But most publishers expect the vast majority of users not to sign off on having their behavior tracked. So advertisers will know much less about the people they’re trying to reach and what those people do when they encounter their ads. That’s almost certain, in the near term, to reduce the prices of the ads they sell because advertisers will find them less effective.

We don’t know exactly how that will play out for publishers who rely on that kind of targeted advertising for revenue. But we can take a guess: In 2017, Apple rolled out a similar restriction on behavior tracking for its Safari web browser, and publishers saw ad rates plummet for Safari users.

Conventional industry wisdom is that Facebook, in particular, as well as Google, will have to rethink the way they sell their ads and are likely to see revenue get hit along the way.

Facebook has already put out research suggesting that its ad network, which runs ads on other publishers’ sites and apps, could see revenue drop by half if targeted advertising, which relies on tracking users’ behavior around the internet, goes away. And during Facebook’s most recent earnings call, chief financial officer Dave Wehner said Apple’s changes would create a “challenging headwind,” and that “it is something that people need to take very seriously. … It’s an area of concern.”

It’s possible that most of the changes will be limited to the very biggest players in internet advertising because you need apps with very large user bases — likely 10 million monthly users or more — to make money selling those kinds of automated, targeted ads. Which is one of the main reasons Facebook and Google are already swallowing up the majority of digital ad dollars.

But DMG’s Clarke says the move will hit his company, even if it’s small compared to the giants. “Untargeted ads are basically worthless,” he says. Clarke says he thinks the revenue his company’s iOS app users generate could drop by 75 percent, which could prompt him to abandon the app altogether and ask his readers to read the Daily Mail on the web instead.

But other publishers are less worried about the effect on their app ad revenue and more concerned that Apple is attempting to change digital advertising on its own.

“The instinct’s in the right place,” says Julia Beizer, who heads up digital for Bloomberg Media. “We all want to make a better, privacy-safe web. But rolling it out without consulting the industry means you’re asking publishers to bear the brunt of the sins of ad tech. Which isn’t fair.”

Other publishers say the move away from targeted ads could conceivably be a good thing for them because it would lessen the advantage Google and Facebook get from combining their massive pools of data about users’ behavior on their own app with the information they collect about what they do outside their apps.

“If the playing field is level, and no one can track users and data, that’s bad for ad tech,” says Jason Kint, who heads up Digital Content Next, a publishers trade group. “But the world’s going this way.”

For example, the New York Times, which had already announced that it would be phasing out the use of data collected by other companies to target ads for its readers, says it simply won’t use third-party tracking data for its Apple app this fall once the changes kick in.

Rebecca Grossman-Cohen, who heads up strategic partnerships for the Times, says the move creates “some loss” of advertising revenue, but it will be “minimal.” She says that Apple essentially sped up a decision the Times would have reached anyway: “We could fairly say we would have gotten to a similar place in any event.”

Which is more or less what Apple wants to convey. The company didn’t want to talk on the record, but executives there say they made the move to reduce tracking on its apps as an extension of other moves they have made to increase users’ privacy, like limiting targeting on Safari and requiring apps to get permission to track users’ location.

It is possible that Apple’s move to upend internet advertising will bring more scrutiny to the company, which is already fending off high-profile antitrust charges from Spotify and Epic Games. Last week, a group of publishers, including the New York Times, sent Apple a letter demanding better terms for the subscriptions it sells through its App Store. And the Daily Mail intends to complain to the US Department of Justice about Apple’s ad changes, according to a person familiar with the company’s plans.

But the move also illustrates the fact that big tech companies aren’t just under pressure from lawmakers and government regulators — they’re also fighting each other.

Facebook, for instance, has already complained publicly about Apple’s App Store policies twice this month. And it criticized Apple again in late August, while announcing that it simply won’t use Apple’s device identifier on its own apps.

That means Facebook won’t have to show users that pop-up screen asking for permission to track them across the web. But it’s unclear how much third-party data Facebook will use for its ad targeting, or what Apple’s reaction to Facebook’s move will be.

Facebook has already told Wall Street that it expects Apple’s new rules to affect its business. But today it is leaning into the idea that the change will mostly hurt publishers that use Facebook’s ad network to place ads on their own sites — and that it may ultimately have to shutter the network on Apple devices altogether.

And just in case you didn’t get the political message Facebook is trying to deliver here, they spelled it out for you: Apple, not Facebook, is hurting small developers and publishers. “We understand that iOS 14 will hurt many of our developers and publishers at an already difficult time for businesses,” the company wrote on a blog post announcing its decision. “We work with more than 19,000 developers and publishers from around the globe and in 2019 we paid out billions of dollars. Many of these are small businesses that depend on ads to support their livelihood.”

Facebook is worth $800 billion. Apple is worth a staggering $2 trillion. Both companies are going to be fine no matter how this shakes out. And this is a fight about advertising technology, and even people who work in advertising technology for a living are bored by advertising technology. But watch this space: The way this brawl affects internet ads and the stuff that runs alongside them — the stuff you want to see — is worth watching.

New goal: 25,000

In the spring, we launched a program asking readers for financial contributions to help keep Vox free for everyone, and last week, we set a goal of reaching 20,000 contributors. Well, you helped us blow past that. Today, we are extending that goal to 25,000. Millions turn to Vox each month to understand an increasingly chaotic world — from what is happening with the USPS to the coronavirus crisis to what is, quite possibly, the most consequential presidential election of our lifetimes. Even when the economy and the news advertising market recovers, your support will be a critical part of sustaining our resource-intensive work — and helping everyone make sense of an increasingly chaotic world. Contribute today from as little as $3.

Will you help keep Vox free for all?

Millions of people rely on Vox to understand how the policy decisions made in Washington, from health care to unemployment to housing, could impact their lives. Our work is well-sourced, research-driven, and in-depth. And that kind of work takes resources. Even after the economy recovers, advertising alone will never be enough to support it. If you have already made a contribution to Vox, thank you. If you haven’t, help us keep our journalism free for everyone by making a financial contribution today, from as little as $3.

Sourse: vox.com