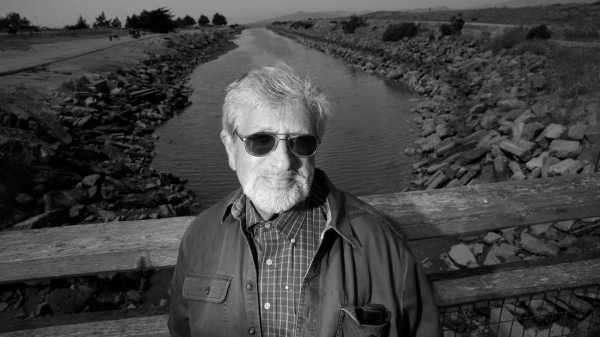

The imperiously brilliant music historian Richard Taruskin, who died on July 1st, at the age of seventy-seven, combined several qualities that are seldom found together in one person. He was, first of all, staggeringly knowledgeable about his chosen field. His near-total command of the history and practice of classical music engendered “The Oxford History of Western Music,” a five-volume, forty-three-hundred-page behemoth, which Taruskin published in 2005. His ability to hold forth with equal bravura on Gregorian chant, polyphonic masses, Baroque concertos, and Russian opera was grounded not only in profound learning but also in deep-seated musicianship. A Queens native and a graduate of the High School of Music & Art, Taruskin played the viola da gamba for many years on New York’s early-music scene; as a choral conductor, he made fascinating recordings of Renaissance repertory with the New York group Cappella Nova. Later, ensconced on the faculty of the University of California, Berkeley, he stepped away from performance, but a fundamental musicality animated everything he wrote.

People with encyclopedic minds are often paralyzed by the sheer quantity of what they know. Taruskin could step back from the crowd of facts and marshal them into mobile lines of thought. As the musicologist William Robin noted, in a Times obituary, the defining thesis of Taruskin’s career was his insistence that music cannot be detached from social reality and confined to an autonomous sphere. Today, with the discussion of art heavily politicized, the point may seem banal, but Taruskin had grown up in a different age, one in which formalist aesthetics prevailed. Classical music was held to be a “kingdom . . . not of this world,” in the words of the arch-Romantic author E. T. A. Hoffmann. In this view, which has hardly died away, eternal masterpieces float above the mire, communing with one another across time.

In tackling that paradigm, Taruskin chose as one of his primary battlefields the œuvre of Igor Stravinsky, who once proclaimed that “music is, by its very nature, essentially powerless to express anything at all, whether a feeling, an attitude of mind, a psychological mood, a phenomenon of nature, etc.” The “etc.” can be assumed to contain politics. Taruskin’s two-volume treatise “Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions,” from 1996, showed that once the composer became a bulwark of Western modernism he minimized his ties to the traditions in question—in particular, his huge debt to his teacher, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Taruskin’s early focus on Russian music was itself a defiant gesture, because the field had been considered a musicological backwater. The Germanic bias of the instrumental canon was Taruskin’s chief bugbear; he resisted the idea that Bach and Beethoven are “universal” in appeal while Tchaikovsky and Rimsky-Korsakov are merely national. He liked to quote an ironic comment by the political scientist Stanley Hoffmann: “There are universal values, and they happen to be mine.”

Taruskin was by no means the only scholar of his generation who challenged the moldering norms of classical-music discourse. In a similar spirit, Lydia Goehr analyzed the canon as a constructed museum and Susan McClary drew attention to gender, sexuality, and race. Indeed, McClary’s approach was more radical—and, these days, has become more influential. If Taruskin confronted German chauvinism in concert culture, McClary went further, questioning the male chauvinism that underpinned the entire structure. The shift that she helped to bring about is evident in recent efforts to incorporate the likes of Fanny Mendelssohn and Florence Price into the repertory.

What ultimately made Taruskin a singular phenomenon—and, to my mind, the most formidable modern writer on music—was not what he wrote but how he wrote it. He possessed a fluid, engrossing style, seamlessly mixing the literary and the conversational, the meticulous and the evocative. Even when his prose delves into technical thickets, it keeps rolling forward. In one section of the “Oxford History,” he uses Mozart’s Fantasia in C Minor to conjure up the vast expanse of improvised music that went unrecorded across the centuries. Another of his recurring themes was the defense of virtuoso display against snobbish scolds, and he relished the opportunity to harness the sublime Mozart to his cause:

To sum up this remarkable composition-in-the-form-of-an-improvisation, or improvisation-in-the-form-of-a-composition: its technique, basically, is that of withholding precisely what a sonata or symphonic exposition establishes, proceeding from key to key and theme to theme not by any predefined process of “logic” but in a “locally associative” process that at every turn (or, at any rate, until the retransition and recapitulation signal the approaching end) defies prediction. In place of a reassuring sense of order, the composer establishes a thrilling sense of danger—of imminent disintegration or collapse, to be averted only by an unending supply of delightfully surprising ideas such as only a Mozartean imagination can sustain. That sense of risks successfully negotiated is the same awareness that makes a virtuoso performance thrilling. In the fantasia, as in the improvisations it apes, composing and performing were one.

In Taruskin’s writing, likewise, scholarship and journalism were one. When he took to the pages of the Times, the New Republic, or the classical-music magazine Opus, he did not need any substantial change in his stylistic gears, although a more streetwise voice would come into play. Only he could have opened an article about John Cage with a Lenny Bruce-inspired description of the composer as music’s “scariest goy.”

Taruskin also had a bent for invective, which he exercised freely. Sometimes it was deserved, as when he laid waste to Solomon Volkov’s “Testimony,” the alleged memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich, or to the urban legend of Tchaikovsky’s suicide. In other cases, Taruskin went astray. In 1996, he launched a bizarre assault on the twelve-tone composer Donald Martino, dismissing his music as both “arcane” and “simplistic.” If the composer had been a widely hailed colossus, Taruskin’s use of the hyper-amplified Times pulpit might have been justified; but Martino was nothing of the sort, and the harangue had a bullying bark. Even more unsettling were Taruskin’s polemics against John Adams’s opera “The Death of Klinghoffer.” In a piece published not long after the September 11th attacks, he accused Adams of “romanticizing terrorists” and of playing to “anti-American, anti-Semitic, anti-bourgeois” prejudices. When, in 2014, the Met staged “Klinghoffer,” the production was greeted by a reactionary, proto-Trumpian protest rally that featured Rudolph Giuliani. I was dismayed, but not surprised, to hear one of the speakers invoke Taruskin’s name.

He relished whipping up controversy—few Times critics can ever have elicited so many expostulating letters to the editor—but he also spent an inordinate amount of time bickering with his opponents. In later years, he collected his journalistic and scholarly essays in a series of volumes for the University of California Press—“The Danger of Music,” “On Russian Music,” “Russian Music at Home and Abroad,” and “Cursed Questions”—and the squabbling dragged on in the postscripts, which occasionally ran longer than the articles themselves. In the case of the “Klinghoffer” imbroglio, Taruskin protested that, although he had charged Adams with catering to anti-Semitism, he had not accused the composer of being anti-Semitic, per se—just the sort of weaselly evasion he would have lambasted in another’s writing.

If self-absorption sometimes got the better of him, his principal achievements—the “Oxford History,” “Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions,” and the essay collections “Musorgsky,” “Defining Russia Musically,” and “Text and Act,” the last a scouring overview of the early-music field—still tower over the literature. Even the diatribes document the urgency that he brought to every discussion. An underlying agenda of Taruskin’s work was his drive to convince nonspecialist readers that music mattered—not in some timeless fairy-tale realm but in the fraught lives of twentieth- and twenty-first-century people. He made clear that something enormous and vital was at stake. His aggressions would have caused less of a stir in the combat zones of literature, art, or the cinema; only in the churchly atmosphere of classical music did they amount to a scandal. Taruskin’s refusal to speak in hushed tones was salutary.

At this point, I seem to hear Taruskin saying, “How long are you going to keep up this voice-of-God routine, Alex?” Fair enough: I knew Richard for almost thirty years and idolized him from the start of my own career as a critic. Indeed, his articles for the Times and the New Republic in the late eighties and early nineties got me interested in the idea of writing about music for a living. I emulated him, as best I could. He took notice of me and sent a postcard.

Most of the obituaries for Richard mentioned the postcards—curt notes that he fired off to colleagues and critics. Later came brisk e-mails, from an intermittently hacked AOL account. I have a considerable collection of these Taruskin-grams, which identified instances of puffery, cant, cliché, and coasting in my work. In 1995, I ended a Times piece about wartime recordings by Richard Strauss with the following: “It might be wishful thinking, but the terrible anguish that wells up in the 1944 ‘Death and Transfiguration’—is this, perhaps, remorse?” A few days later came the postcard: “Dear Alex, Wishful? U-bet. And not just at the end. All best Richard T.” My first instinct was always to bristle, although on reflection I often realized that he was right, or at least not wrong. Certainly, he had a point about Strauss’s remorseless performance of “Death and Transfiguration.”

Get a thicker skin, Richard liked to say. A big, burly guy, he had a macho strain in him—a pugilistic vision of intellectual life. Although his needling could edge into cruelty, he was ultimately generous toward younger scholars, generating countless recommendations and blurbs over the decades. He saved his hardest punches for heavyweights such as Pierre Boulez, Charles Rosen, and Robert Craft. For my part, I became inured to his brickbats and grew to enjoy the back-and-forth. In 2006, I sent him the completed manuscript of my first book, and, instead of brushing it aside, he did me the honor of disputing it on almost every page. Here are some of the annotations:

Puh-leeze.

Cool the pitch, bub.

This is all such bullshit.

Thank you, Cornelius Ryan.

Ryan was the author of such florid military histories as “The Longest Day” and “A Bridge Too Far.” Other Taruskin comments included “Oy,” “Nah,” “Yawn,” and, of course, “Weasel.” At first, I was dismayed; then I began to laugh. Again, he was often right, and his directness seized my attention. An author in the numbed final stages of writing a book has no use for feedback along the lines of “This is wonderful, but I had a slight hesitation about your formulation. . . .”

In recent years, after Richard retired from teaching, his missives lost their customary brusqueness and became more discursive. Facing various health problems, he looked back on his eventful life, speaking often of his upbringing in a leftist, Jewish, intellectual milieu. When I quoted W. E. B. Du Bois in one of my pieces, he recalled marching with his mother at the 1963 March on Washington, during which the news of Du Bois’s death, in Ghana, spread through the crowd. He remembered seeing the physically racked figure of Dmitri Shostakovich acknowledging applause at the première of his Fifteenth Symphony, in Moscow, in 1972. He recounted avant-garde happenings that required a rogue viola da gamba. This backward-looking gaze will be evident in his final book, “Musical Lives and Times Examined,” which the University of California Press plans to publish next year. He was busying himself with the final draft as esophageal cancer advanced.

Richard’s glorious brain kept firing on all cylinders to the end. In late June, before I realized how sick he was, I told him of the death of the legendary New Yorker fact-checker Martin Baron, who had mined Richard’s omniscience for many decades. Richard replied:

The first time I ever received a call from Martin it was after a Cappella Nova concert in which we did some motets from the Choralis Constantinus and Andrew Porter [The New Yorker’s music critic from 1972 to 1992] reviewed the concert quite enthusiastically. So then Martin calls and says, in perfect New Yorker-ese, “We want to call the Choralis Constantinus ‘monumental volumes.’ Do you think that is a fair description?” I was always tickled when I thought about The New Yorker’s idea of what a fact was.

I looked up the review in question. The word “monumental” does not appear. I pictured Richard saying to Martin, “ ‘Monumental?’ Puh-leeze.”

A voice as powerful as Richard’s cannot die away. It reverberates in his books, which will be cited as long as people think and write about music. It echoes in my mind as I work, warning me against the cheap phrase and the lazy move. What I took most to heart was his edict that love should never devolve into worship. The intensity of his own passion for music compelled him to grapple with the darkness that dwells in all man-made things. Richard was my ultimate reader, my final arbiter, and I can’t bring myself to accept his absence. On some days, I choose to pretend that he is still out there somewhere, and that the lack of prickly messages in my in-box means I have written nothing particularly weak of late. Wishful? You bet. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com