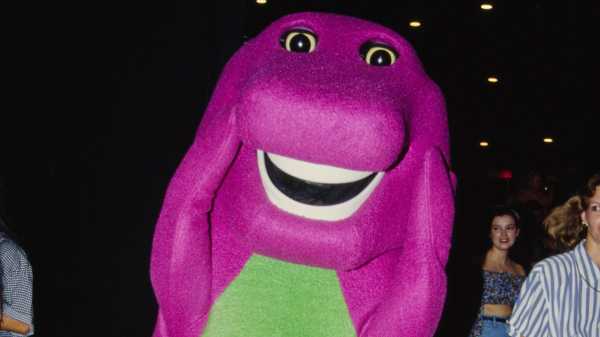

The new documentary “I Love You, You Hate Me” uses Barney to examine a broader phenomenon.Photograph by Vinnie Zuffante / Michael Ochs Archives / Getty

What made Barney, the purple dinosaur and nineties kids’-TV sensation, so infuriatingly loathsome? Was it his doofy voice and inane giggle, coming at you like a low-watt Pillsbury Doughboy? His menacing rictus and unnerving hat-band strip of teeth? His shameless abuse of nursery rhymes? His indifference to the anxious smiles on his young friends’ faces as they all danced in lockstep to “Indoor-Outdoor Voices”? The short answer is yes, it is all those things, and, as a result, he and his show inspired an acute degree of animosity; a new two-episode docuseries from Peacock, “I Love You, You Hate Me,” dares to investigate. Directed by Tommy Avallone, the series takes a “Behind the Music”-style approach to the “Barney & Friends” phenomenon, juxtaposing the show’s wholesomeness and wild popularity with end-of-innocence stunners. “I got dismemberment-of-my-family e-mails because of my music,” the show’s music director, Bob Singleton, says. (“It’s believed the Pentagon forced prisoners at Gitmo to listen to ‘Barney’ for twenty-four straight hours,” a newscaster adds.) The documentary purports to examine our collective impulse to hate, but it also wants to spill some beans—to reflect, gawk, shudder, and heal—and, in true “Barney” spirit, it pursues its mission while resisting nuance. “People couldn’t accept that this was just a show, that it talked about nice things and nice emotions and love and caring,” Al Roker says, frowning on a sofa. “And so let the bashing begin!” Don’t mind if I do.

“Barney & Friends” ran on PBS from 1992 to 2010. In it, a bunch of peppy children hang out at what appears to be an abandoned nursery school, and in later seasons, a park, unsupervised except for a six-foot dinosaur; the dinosaur is the authority figure, yet the children have made him up. Lest we doubt this, the show’s snappily militaristic theme song, a dulled-down riff on “Yankee Doodle,” sung by children, spells it out: “Barney is a dinosaur / from our imagination,” and so on. The dinosaur and the kids—a diverse group of youngsters, brimming with forced cheer—sing strenuously wholesome songs and dance in awkward syncopation. In one episode, they jump rope while chanting about chores, as most kids do. (“Daddy! Daddy! Let’s wash the car! Daddy! Daddy! And jog really far!”) Barney’s signature hit, “I Love You,” conveys the essence of the show’s approach, from the values-focussed lyrics (“I love you / you love me / we’re a happy fam-i-ly”) to the pacing (plodding, joyless) to the melody (“This Old Man,” robbed of its knick-knack-paddywhack zing). The whole enterprise leads with safety and didacticism while insisting it’s having fun. I was in college during Barney’s rise to power, and in my memory, Barney, unlike Big Bird and other expressive, sensitive Muppets of my youth, had a completely immobile face, like a sports mascot. He did not, I now realize—his eyes and mouth moved—but immobility was the effect, because that grin wasn’t going anywhere.

“I Love You, You Hate Me” shows that Barney’s creators meant well. The character was created in 1988, in a Dallas suburb, by Sheryl Leach, who’d grown up in the area. (Leach declined to participate in the documentary; we get to know her and her family through archival footage and others’ descriptions.) “I went to high school with Sheryl,” a friend says. “I’m from a Christian background, and we kept the same moral code.” Leach taught school for several years before working at a family-run company, Developmental Learning Materials, where she met her husband. In 1986, the Leaches had a son, Patrick, who became a “very active” two-year-old. One of the rare videos to hold his attention was “Wee Sing Together,” which combined group singing with an anthropomorphic mouse and bear, and Leach wanted to create something similar, with educational elements, “tailor-made for the preschool audience.” In an old interview, Leach says, “I didn’t have a background in video at all, but I thought, you know, How hard can it be?” Her father-in-law’s company had a production studio, and soon they were making a show.

Leach considered focussing on a Teddy bear, but Patrick loved dinosaurs. “Kids of all ages are fascinated with dinosaurs,” Bill Nye, a fellow PBS veteran, tells us, waving his hands around. “They’re monsters, they’re vicious—a high-stakes life style.” Leach didn’t want Barney to have sharp teeth—or, the original head writer says, too much personality. He had envisioned a “fun, wisecracking” Barney, inspired by Bruce Willis’s character in “Moonlighting.” Leach had other ideas. “I got a letter firing me,” the writer says, laughing: “ ‘We have decided that you have a creative spirit that cannot be contained.’ ” The creators wanted a lead actor who’d done voice-overs for McDonald’s and Chuck E. Cheese, but he was too tall for the costume, so they hired a separate body actor. Then that guy joined the military, and they hired an exuberant dancer, David Joyner, “who made Barney the athletic Barney that he is today,” an interviewee says. Joyner, who in 2018 was outed as a tantric-healing practitioner, says, “Before I got in costume, I’d pull up my Kundalini energy. Just imagine: love, love, love, love, love, love, love.” (A flurry of interviewees nervously distance themselves from whatever they imagine his work to be.) The team also hired an ethnically diverse group of local kids. The resulting series of home videos, “Barney and the Backyard Gang,” gained popularity in Texas; live Barney performances began to sell out, and the phenomenon eventually caught the eye of Larry Rifkin, the head of programming for Connecticut Public Television, who helped adapt it for PBS. Barney mania was under way.

Like Penny Lane’s documentary “Listening to Kenny G,” from 2021, “I Love You, You Hate Me” uses a polarizing cultural figure to examine a broader phenomenon. “Listening to Kenny G” asks questions about taste, virtuosity, and what we love about music and art; “I Like You, You Hate Me” makes a few such observations (three-year-olds crave repetition, though it drives parents crazy) but mostly decides that Barney is a gentle show about love and acceptance and that haters, essentially, couldn’t handle those things. We learn a lot about the hatred itself: an I Hate Barney Secret Society started by a Florida dad, an organization called the Jihad to Destroy Barney. Footage of violence against stuffed Barney toys—shooting them with a gun, hitting them with a hammer—is shown again and again. All of this became stressful for the people involved—but the film’s interviewees describe the experience of making the show, and of working with Leach, with almost painful wistfulness. Some former “Barney” kids seem to have enjoyed themselves more than I suspected. “They gave me a story line with my Filipino heritage, which is awesome,” Pia Hamilton, who appeared in the first three seasons, says, brushing away tears. “I got to sing ‘Happy Birthday’ in Tagalog.”

The love and togetherness wasn’t “Barney” ’s problem. The character himself was uniquely unnerving—more Grimace than T. Rex, somehow dopey and condescending at once—and some of the outrage, I suspect, came from viewers’ impassioned feelings about what good educational TV should be. On PBS, “Barney” coincided with the rise of Elmo, the cutesy, shrill, baby-talking Muppet, who, as “Sesame Street” viewership aged down, began to elbow the show’s more lovable characters aside. (In 1996, Tickle Me Elmo mania caused pre-Christmas melees.) In 1997, parents encountered “Caillou,” another preschoolers’ show on PBS, and quickly despised it; the show’s lessons, however useful, were delivered by a whiny, confusingly bald-headed child. Some nineties kids’ TV edified without pandering. “Where in the World Is Carmen Sandiego?” paired jaw-dropping geography expertise with ridiculously catchy a cappella; the BBC’s bonkers “Teletubbies” mesmerized preschoolers (and twentysomethings, such as my friends and me) with near-psychedelic wonderment and joy, presenting a world that seemed made by toddlers for toddlers, and that embraced humans as they were.

“Barney,” unlike those shows and classics like “Sesame Street,” “Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood,” and “Zoom,” felt primarily instructive, so goody-two-shoes it hurt. The mid-century children’s-book visionary Ursula Nordstrom, editor of Maurice Sendak, E. B. White, Louise Fitzhugh, and several other geniuses, had a motto—“Good books for bad children”—which was shorthand for a spirit of intelligence and fun, a zeal to improve upon books like “Dick and Jane,” which primly told children how to be. The creators of “Barney” seem like fine people with fine intentions, but they had a Sunday-school vision of child behavior. On “Mr. Rogers” and “Sesame Street,” the kids were the age of the average viewer, and they spoke naturally, with pauses and thoughts and occasional giggling. “Barney” was as tightly blocked and scripted as a toy commercial, with nine-year-olds shouting about how happy they were and how much they loved Barney. “Boy, Barney! You sure know some great games!” a boy says, in one episode, after participating in a hand-jive performance of “Mr. Knickerbocker.” Then Barney tells a knock-knock joke, and the boy yells, “You sing, you dance, you make us laugh—you do just about everything!” Today, the most popular streaming “Barney” song is “Clean Up” (“Everybody do your share!”); another, “Brushing My Teeth,” is a snazzy, off-key assertion of the fun of dental care. (“I hate to stop!” Barney wails, adding, “I never let the water run.”) It’s possible to write zippy, genuine songs about days of the week, numbers, housework, and feelings, but “Barney” is so fiercely inoffensive that it actually becomes offensive, implying that normal human behavior, with all its weirdness and humor and misunderstandings, is too dangerous to accurately represent. To Barney haters, it’s obvious that “Barney”—rather than an effort to connect, to acknowledge who children are—is an instrument of control.

Watching “I Love You, You Hate Me” humanizes the people behind the scenes, and that helps. Andrew Olsen, a wide-eyed young man who runs Barney History Fans, an online fan club, serves as a kind of narrator, a row of plush Barneys behind him as he weighs in on topics like the arc of the Leaches’ marriage. (The family ultimately endured hardship: divorce, a suicide, an episode of violence.) Why does Olsen love the show? “ ‘Barney’ transports me back to a time when I didn’t have any worries or cares in the world,” he says. As the documentary zooms in on the Barney hatred, it begins to connect that giddy ragefest to the present; a former neo-Nazi warns us about “basing your identity on what you hate,” and a former “Barney” actor laments that “it’s like no one learned the lessons that Barney was trying to teach—to love each other, to share, to be kind.” But part of why people despised “Barney” was that they knew these lessons could be taught with complexity and heart. In “Street Gang,” a history of “Sesame Street” by Michael Davis, James Taylor, who once sang a grouchified version of “Your Smiling Face” to Oscar the Grouch, praises the show’s creative daring, observing that characters like Bert, Big Bird, and Cookie Monster, vividly distinct in personality, suggest to kids “other ways of seeing themselves.” “The wonder of ‘Sesame Street’ is that it has never tried to wrap children up in cellophane,” Taylor says. “It’s as if the show has been saying, ‘Come on and join the real world.’ ” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com