The launch of The American Conservative in October 2002 was itself an act of dissent, either courageous or quixotic depending on your point of view. When it appeared on newsstands, volume 1, number 1 made it clear that TAC was to be an anti-establishment journal. So the magazine has remained in the ensuing years, a testament to principled consistency.

This has been notably true on all matters related to America’s role in the world. Since TAC’s founding, editors have come and gone. Yet throughout, the magazine has kept faith with the position staked out in its inaugural editorial, which denounced “fantasies of global hegemony” and promised to oppose temptations of “go-it-alone militarism.”

At that very moment, the corridors of power in Washington were awash with fantasies of global hegemony, while in both liberal and conservative quarters, go-it-alone militarism had become almost de rigueur. In an immediate sense, a prospective U.S. invasion of Iraq represented the pressing issue of the day. The nominal purpose of the forthcoming war was to rid the world of Saddam Hussein, putative ally of Osama bin Laden and supposed developer of nuclear weapons. Yet lurking behind this tissue-thin cover story were ambitions that went far beyond overthrowing one particularly noxious dictator.

Among the hegemonists and the militarists, the unstated but widely understood purpose of invading Iraq was threefold. First, it would convert the so-called Global War on Terrorism from a reactive into a proactive enterprise. The United States was going permanently on the offensive. In Iraq, it would demonstrate the efficacy of employing carefully tailored violence—no need for “overwhelming force”—to eliminate threats even before they had fully formed. No longer would Washington deem war a last resort.

Second, embarking upon this war of choice without the sanction of the United Nations and in defiance of world opinion signaled that the United States was exempting itself from norms to which all others were expected to comply. By winning a decisive victory in Iraq, the United States would arrogate to itself the singular privilege of waging preventive war.

Finally, a successful “liberation” of Iraq, aligning that nation with Western values and American purposes, would demonstrate the feasibility of coercive transformation and establish a precedent for its further application elsewhere in the Islamic world. In other words, Iraq was just for starters.

A remarkably broad swath of establishment worthies signed onto this project with evident enthusiasm. Call it the Lewis-Ledeen coalition, extending all the way from the eminently respectable Bernard Lewis to the eminently disreputable Michael Ledeen. Or, better still, call it the Pax Americana cartel.

From his perch at Princeton University, Professor Lewis took to the pages of the Wall Street Journal to argue that it was “Time for Toppling.” According to Lewis, a renowned authority on the Islamic world, not only Iraqis but all Arabs and also Iranians would welcome liberation at the hands of U.S. forces. He dismissed out of hand the notion that “regime change in Iraq would have a dangerous destabilizing effect on the rest of the region, and could lead to general conflict and chaos.”

A regular contributor to National Review, Ledeen viewed the possibility of war with all the delight of an eight-year-old playing with his first set of toy soldiers. Ledeen differed with Bernard Lewis on one point only: If invading Iraq destabilized the region, then all the better. “One can only hope that we turn the region into a cauldron, and faster, please.” If ever there were a region that richly deserved being “cauldronized,” wrote Ledeen, it was the Middle East. He emphasized that deposing Saddam was just a first step. After it finished with Iraq, the United States should go on to “bring down the terror regimes” in Iran, Syria, and Saudi Arabia. This, he concluded, represented America’s true “mission in the war against terror.”

The roster of writers, editors, and talking heads subscribing to the Lewis-Ledeen school of American statecraft is long and impressive. A partial list of prominent members runs the gamut from A to Z, beginning with Ken “Cakewalk” Adelman, and including Peter Beinart, William Bennett, Paul Berman, Max Boot, David Brooks, Tucker Carlson, Thomas Friedman, at least two Goldbergs, Sean Hannity, Victor Davis Hanson, Christopher Hitchens, several Kagans and Kaplans, William Kristol, Charles Krauthammer, Rich Lowry, the Rev. Richard John Neuhaus, Bill O’Reilly, George Packer, Richard Perle, Anne-Marie Slaughter, Andrew Sullivan, Leon Wieseltier, and George Will, with Fareed Zakaria bringing up the tail end.

The nominally conservative National Review endorsed the idea of invading Iraq as did the nominally liberal New Republic. The editorial pages of the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and Washington Post were positively gung-ho to go after Saddam. As for The Weekly Standard, it’s a wonder that younger staffers eager to join in the fun didn’t rush off to their local Armed Forces Career Center to enlist.

In terms of intellectual firepower, the Pax Americana cartel both outnumbered and outgunned the antiwar camp. True, Michael Moore, Brent Scowcroft, Edward Kennedy, and the Dixie Chicks expressed opposition to the war. So too did Pope John Paul II, who to the dismay of Catholic neoconservatives denounced the coming invasion of Iraq as “a defeat for humanity.” In this instance, if in few others, the left-leaning Nation magazine agreed with the right-leaning pope. And standing shoulder-to-shoulder with The Nation was its ideological opposite: the brand new American Conservative.

Fifteen-plus years after it appeared, TAC’s premiere issue stands up remarkably well. The yellowing cover of my copy fairly shouts its warning against the impending “Iraq Folly.” The cover art by Mark Brewer depicts an unhinged Uncle Sam wielding an oversized fly swatter as he prepares to clobber an insect-like Saddam. In the background, figures representing the rest of the world react with horror.

The cover accurately prefigured the issue’s contents. Within were several essays that can only be regarded as prescient, with Patrick Buchanan, TAC’s co-founder, appropriately leading off. Buchanan began his column with a quotation from the British historian A.J.P. Taylor. “Though the object of being a Great Power is to be able to fight a Great War,” Professor Taylor had written, “the only way to remain a Great Power is not to fight one.” Buchanan foresaw a war in Iraq putting American preeminence needlessly at risk.

Getting to Baghdad was not the problem. Once there, he asked, “how do we get out?” Buchanan mocked expectations of the Lewis-Ledeen clique that an easy win in Iraq was going to pave the way for success elsewhere in the region. “To democratize, defend, and hold Iraq together,” he predicted, “U.S. troops will be tied down for decades.” Reminding readers that “the one endeavor at which Islamic peoples excel is expelling imperial powers by terror and guerrilla war,” he expected an American occupation of Iraq to incite sustained and stubborn resistance.

Others expanded on Buchanan’s argument. And in the months and years that followed, events in Iraq and in other distant parts of the American imperium vindicated these warnings. From one issue to the next, TAC reinforced and amplified its critique of militarized hegemony. In essays and editorials, it denounced the imperial thrust of U.S. policy as a violation of everything that the nation claimed to represent. It did not depart one inch from the position staked out in its inaugural editorial.

Yet, although the analysis in TAC has been on the mark, its critique has had little discernible impact on the foreign policy establishment. Henry Clay once remarked that he’d “rather be right than be president.” On foreign policy, TAC has generally been right, but presidents and those who advise presidents haven’t bothered to take heed.

Granted, since 2002-03, the ranks of the Lewis-Ledeen coalition have thinned. Remaining coalition loyalists tend to be less strident than they were back then. The once popular battle cry—“Anyone can go to Baghdad. Real men go to Tehran”—has been retired, although the irrepressible and uneducable Ledeen may not have gotten the memo. He’s still pressing for regime change in Iran and “faster, please.”

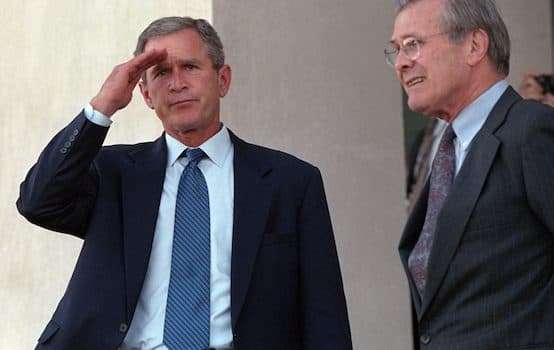

Some charter members of the Lewis-Ledeen confederation have even recanted (although very few have ceased to opine). Most, however, still defend their advocacy of invading Iraq. The idea was a good one, they insist; the execution was flawed. If they themselves erred, it was in failing to anticipate the egregious incompetence of Donald Rumsfeld, L. Paul Bremer, and various senior military commanders beginning with Tommy Franks. How could anyone have known?

Yet even today in establishment circles, belief in the Pax Americana persists, along with an appetite for armed intervention. So too does a studied indifference to costs and consequences. That self-restraint rather than activism marketed under the heading of “global leadership” might merit consideration as a basis for policy remains an intolerable heresy.

To illustrate, consider a recent piece by New York Times columnist Bret Stephens, a Lewis-Ledeen stalwart. There “really is an axis of evil,” Stephens breezily asserts, appropriating a phrase coined in 2002 by a neophyte speechwriter charged with imparting a moral sheen to George W. Bush’s Manichean with-us-or-against-us worldview. Indeed, according to Stephens, the ranks of evildoers have swollen since David Frum devised the phrase. The axis now includes not only original members North Korea and Iran, but also Syria, Russia, and China, with ex officio status conferred on Hezbollah.

Stephens is keen for the United States to dismantle this axis once and for all. Nor does he doubt the feasibility of doing so without, as he delicately phrases it, “burdening ourselves as we did in Iraq.” And with that brief, oblique reference, the Iraq war vanishes from view, banished along with any other unpleasantries stemming from America’s recent adventures abroad. In other words, Stephens has no interest in what happened when the United States last took on this axis that we ourselves contrived. He faces resolutely forward.

Observing world events from behind his desk at the Times, our pundit professes to know exactly how to gain the initiative against this league of evildoers. Step one: “protect our Kurdish allies against their enemies.” Step two: attack Syrian military installations any time that country employs chemical weapons. Step three: “dramatically increase the military price Russia is paying for its intervention” by employing unspecified “covert” means. To Stephens, it appears self-evident that deepening U.S. involvement in the Syrian civil war will create the foundation for “a consistent military and diplomatic strategy.”

All that’s needed to implement this strategy is a president who “understands that our liberal values are the great prerequisite for our global leadership” and who is willing to deploy American power in support of those values. Our current president understands little about liberal values or any other values worthy of the name, of course. But oust Trump in favor of someone committed to sustaining “Pax Americana,” and we’re well on our way to solving the problems of planet Earth.

Stephens rather likes the phrase Pax Americana. He employs it not as some gauzy aspiration and certainly not a snide euphemism for empire. Rather, it describes all that was good about the contemporary international order until Trump appeared on the scene to bollix things up. Pax Americana is a bigger and better version of Free World, the phrase that it supersedes.

Saving the best for last, Stephens wraps up his column with the journalistic equivalent of Kate Smith belting out “God Bless America” to close out her radio show back in the 1940s. “The cause of freedom,” he warbles, “awaits a resurrection.”

It’s tempting to dismiss Stephens as simply a purveyor of drivel. To do so, however, is to commit a grave error. The truth is that even—perhaps especially—in the Age of Trump, he gives voice to a perspective that continues to resonate wherever political insiders congregate. For journalists keen to make a mark, promoting Pax Americana can be a very good gig indeed.

Recall the famous story about a senior staffer with the American Israel Public Affairs Committee having dinner with a noted journalist who expressed skepticism about how much clout the Israel lobby actually wielded. “You see this napkin?” the AIPAC operative replied. “In twenty-four hours, we could have the signatures of seventy senators on this napkin.” In half that time, any lobbyist worth his salt could get 90 Senate signatures on a napkin endorsing the perpetuation of Pax Americana, even if disguised by using weasel words such as “global leadership” or “our responsibility.” Mitch McConnell and Chuck Schumer would arm wrestle for the privilege of signing first.

Throughout the 15 years of its existence, TAC has made the case that in the present century Pax Americana isn’t working. It isn’t working for citizens of the United States, and neither is it working for the recipients of our intended beneficence abroad. Evidence is overwhelming that efforts to maintain American dominion are contributing to disorder, breeding animosity toward the United States, and doing immense harm.

Yet those who occupy (or covet) positions of influence inside the Beltway don’t want to hear that. So they indulge the whimsical promptings of Bret Stephens and his numerous confreres, who offer assurances that with just a tad more “global leadership,” i.e., the threatened or actual use of armed force targeting the world’s ne’er do wells, all will be well.

The juxtaposition between Stephens’s warm endorsement of the “cause of freedom” and his dismissive allusion to the “burdening” caused by Iraq gives away the game. The readers Stephens seeks to inspire with his homilies about resurrecting freedom rarely experience the burdens stemming from any resulting military misadventures. They send others to do so while they themselves cheer from the sidelines.

I submit that this unceasing celebration of Pax Americana by Bret Stephens and others of his ilk may well pose a greater danger to U.S. national security than any of Donald Trump’s whacked-out mutterings on Twitter or self-contradicting decisions.

As for myself, I am more inclined to forgive Trump than smug journalistic proselytizers such as Stephens. The president is merely an ignoramus, so profoundly ill-equipped for his office that he almost surely doesn’t know what he is doing from one day to the next and is almost surely oblivious to the potential relationship between last week’s bombast and this week’s bluster.

But Stephens is not an ignoramus. He is something worse: the dishonest perpetrator of a hoax.

♦♦♦

The product of this hoax, endlessly endorsed by politicians and pundits of nominally different stripes, is intellectual stasis, with all alternatives to Pax Americana ruled out of bounds. Those like Stephens who take it upon themselves to police the boundaries of permissible discourse disallow any serious reexamination of the premises informing basic U.S. policy since World War II and especially since 9/11. Anyone with the temerity to stray from the prescribed path is immediately slapped with the label “isolationist,” the equivalent in other contexts of being called a racist or sexist.

To appreciate the consequences of allowing Stephens and other members of the Pax Americana cartel to dictate the limits of allowable opinion on foreign policy, we need look no further than the crisis of the present moment.

In 2016, Donald Trump distinguished himself from his chief Republican opponents and certainly from Hillary Clinton by saying out loud what many ordinary Americans already suspected: that in terms of immediate threats, it’s not some faraway axis of evil that we need to worry about so much as pervasive stupidity among the managers of Pax America in Washington. In memorable fashion, Trump vowed to “drain the swamp” and to formulate an “America First” approach to policy. If elected, Trump would end the reckless squandering of American power. So, at least, he said.

To the manifest horror of the Pax Americana cartel, the number of voters who liked what Trump had to say sufficed to hand him the presidency. Yet with Trump now barely a year in office, it is safe to say two things. First, while the president has caused conniptions among denizens of that swamp, the likelihood that he will drain it is zilch. It’s doubtful that Trump, whose lies are remarkable even by Washington standards in both frequency and magnitude, ever actually intended to do so. Indeed, if anything, Trump is replenishing the swamp, especially by funneling yet more billions to our bloated and unaccountable national security apparatus.

Second, whatever Trump supporters may have imagined the retrenchment implied by “America First” might look like, what they are getting is radically different. Indeed, to combine the president’s surname with terms like policy or doctrine, which imply at least a modicum of direction, consistency, and clarity of purpose, is deeply misleading. What we have had thus far from the president and the changing cast of characters who ostensibly advise him are random and frequently inconsistent impulses.

Disdaining maps, our pilot navigates by dead reckoning. The hand on the tiller is given to sudden and unpredictable spasms. The ship of state is adrift.

Some observers speculate that the ongoing purge of Trump’s inner circle heralds the belated arrival of consistency, direction, and clarity of purpose. Yet the nomination of the bellicose Mike Pompeo to become secretary of state along with the installation of the demented John Bolton as national security adviser suggest something other than modesty, retrenchment, or any recognizable form of realism. Rather than America First, Trump appears to be opting for America Unhinged as his preferred theme.

Yet consider: Just two years ago candidate Trump swept the field by denouncing the excesses of Pax Americana; today, if we are to take Pompeo and Bolton seriously, the Trump administration seemingly has the axis of evil in its crosshairs. In Washington, “fantasies of global hegemony” and “go-it-alone militarism” are back, having been revived in an especially virulent form.

Bret Stephens and other advocates of U.S. “global leadership” worry that Trump’s passivity endangers American dominion. They urge greater activism. They may just get their wish. Yet should the result be a further round of costly and needless wars, Trump may well be remembered as the president who ushered that Pax onto the ash heap of history.

The ironies abound, but don’t expect Bret Stephens to grasp them. If you’re like me and own a copy of TAC’s volume 1, number 1, put it in a safe place. It is a prophetic document. Perhaps one day the warnings it contains may gain a hearing. Until then, buckle up.

Andrew J. Bacevich is a frequent contributor to The American Conservative.

Sourse: theamericanconservative.com