No one yet knows if there’s going to be a summit with North Korea. But the alternative to a Trump-Kim tête-à-tête should be a different form of diplomacy, not war, as the administration and its cheerleaders have suggested.

When Lord Acton coined the phrase “power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely,” he might have had America in mind. Never mind U.S. leaders’ professed good intentions: possession of extraordinary military power continues to lead otherwise sensible people to pursue dangerous, even monstrous policies.

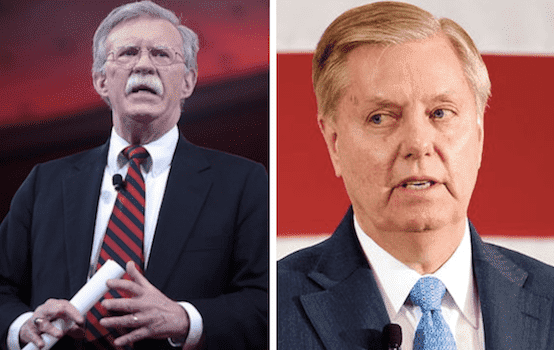

So it is with North Korea. President Donald Trump beat the war drums loudly last year. He sounded a lot like Kim Jong-un when he threatened to visit “fire and fury” upon the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. Senator Lindsey Graham led the Greek chorus in support of the administration, amplifying the president’s threats.

Never mind the consequences of a Second Korean War. “Japan, South Korea, China would all be in the crosshairs of a war if we started one with North Korea,” Graham admitted. But that would just be unfortunate collateral damage. “If there’s going to be a war to stop [Kim], it will be over there. If thousands die, they’re going to die over there. They’re not going to die here,” he explained.

- Trump’s Reckless Rhetoric on North Korea and Libya

- North Korea and Iran Don’t Seem Particularly Intimidated

The prospect of a summit between Trump and Kim halted the talk of war. But on May 20, Graham began spewing threats anew. On Fox News he declared that “If [the North Koreans] don’t show up that means diplomacy has failed.” Which in turn “puts us back on the path to conflict. It would be time to take American families and dependents out of South Korea.” Or if the North Koreans “do show up and try to play Trump, and that means military conflict is the only thing left.”

But, he promised, “they will lose it, not us.” Thus, “President Trump is going to end this problem with North Korea one way or the other, and he should.”

Shortly thereafter North Korean officials objected to John Bolton’s talk of the “Libya model,” which resulted in the ouster of Moammar Gaddafi after he agreed to close his missile and nuclear programs. (Bolton was involved in negotiating the surrender of Gaddafi’s weapons. In 2011, he publicly called for the U.S. military to take out the Libyan leader.)

The implications for Kim were obvious—too obvious for Bolton not to be aware of, which is why some observers suspect he meant to sink the summit. Yet rather than dismiss Bolton’s implied menace, the president responded with a threat: “If you look at that model with Gaddafi that was a total decimation, we went in there to beat him…that model will take place if we don’t make a deal [with Kim] most likely.” Vice President Mike Pence followed suit, warning that the North could “end up like the Libya model ended if Kim Jong-un doesn’t make a deal.” Asked if that was a threat, Pence responded: “I think it’s more of a fact.”

As if this will convince Kim to surrender his deterrent.

A day after Trump pulled out of the summit, Graham was again making his rounds, this time on the “Today” show. “If military action is required, they’re going to lose, it will be devastating to the region, and there will be war in China’s backyard,” he proclaimed.

American politicians treat as manifest destiny Washington’s capacity to attack any nation on earth. A handful of countries have capable conventional militaries, but only the few nuclear powers have certain deterrents. Otherwise America alone decides when other nations get bombed, invaded, and occupied. Hence the North’s desire for nukes.

Consider Libya’s experience. In 2003, Libya’s Gaddafi surrendered his WMDs in exchange for geopolitical love from America and Europe. For a time he was well-received—Senators Graham, John McCain, and Joe Lieberman even supped with the seemingly rehabilitated colonel in Tripoli, discussing possible American assistance in the latter’s battle against al-Qaeda. But when rebellion broke out amid the Arab Spring, most of Gaddafi’s sunshine friends suddenly backed regime change, after which he suffered a gruesome end.

It may be that the president’s talk of war is a grand bluff. But even if that’s the case, Trump risks being exposed as a paper tiger. And if it’s not, his reckless course could result in hundreds of thousands or even millions of casualties, depending on the North’s military capabilities. That would be a heckuva way of “protecting” the American people.

The argument for war is wrong-headed in several ways. First, there is no dangerous new North Korean “threat” to the U.S. For 65 years, deterrence has prevented the North from attacking South Korea again. Pyongyang now wants a deterrent so it doesn’t end up as Libya, just another example of national roadkill run over by the American war machine.

There is no evidence that Kim is irrational. To the contrary, he, like his father and grandfather, appears to prefer his virgins in this world. He is not interested in exiting life in a massive nuclear funeral pyre. He knows that the U.S. is capable of destroying his nation multiple times over. He wants to prevent such an event, not trigger it.

Deterrence might feel unsatisfactory to many Americans, but it worked against Joseph Stalin’s Soviet Union and Mao Zedong’s People’s Republic of China. Both were far larger, more powerful, and much scarier than the DPRK. Mao made even nuttier comments than North Korea’s rulers, suggesting that his nation could afford to lose millions of people and still prevail. Yet neither country tested America’s ability to destroy them.

Second, it would be a massive gamble with other people’s lives to assume that Kim would acquiesce to an American attempt to destroy his most important weapons or decapitate his regime. It would be ruinous for his carefully cultivated image as defender of his people. And he could only assume that it would presage an attempt at regime change. To wait would invite the destruction of his military, meaning it would likely lead to full-scale war. A massive U.S. first strike would be no less risky, since Kim could devastate Seoul and Tokyo with just a portion of his weapons—and he would have no reason to hold back.

While Graham—and the president, if Graham is to be believed—might be unafraid of a conflict “over there,” a quarter of a million Americans live in or visit the Republic of Korea every day. To call Americans home would trigger widespread panic in the ROK and alert Pyongyang that war was imminent, inviting Kim to preempt America’s expected attack. U.S. military personnel would die in combat, as well as from possible missile attacks on Guam and Okinawa, home to additional American forces.

Defense Secretary Jim Mattis, no liberal defeatist, warned that such a war would be “probably the worst kind of fighting in most people’s lifetimes.” General Joseph Dunford, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, predicted “a loss of life unlike any we have experienced in our lifetimes.” The Clinton administration predicted as many as one million casualties when it considered attacking the North’s nuclear facilities in 1994.

And that was more than two decades ago. Assuming that a fair proportion of North Korean latest weapons survived initial U.S. attacks, the DPRK could unleash extensive artillery on the South Korean capital of Seoul as well as missiles topped with biological, chemical, and nuclear weapons against multiple targets, perhaps even including Tokyo. The best case would be horrid. The worst case casualty estimate is in the millions. After working to keep the peace for nearly seven decades, it would be madness to risk triggering such a catastrophe.

Third, agreements short of denuclearization may be necessary to have any chance of persuading Pyongyang to disarm, and even limited steps would increase U.S. security. A permanent freeze on nuclear and missile tests would prevent the Kim regime from perfecting its weapons, including building an ICBM that could accurately target U.S. targets. A halt on nuclear weapons production backed by intrusive inspections could cap the North’s arsenal. Reductions in conventional arms could moderate daily military tensions. A peace treaty and diplomatic relations would open communication channels, which are most necessary when the threats are greatest.

Indeed, if the administration is serious about convincing the DPRK to abandon weapons so dearly bought, President Trump should offer to withdraw American troops from the ROK in return for full denuclearization. The president said “we are going to say that [Kim] will have very adequate protection,” but verbal assurances offered no protection for Gaddafi. Kim undoubtedly will require something more. If Washington really wants to eliminate nuclear weapons and build a more peaceful future, it needs to make serious concessions as well.

War with Iraq was not the cakewalk that had been predicted, but it would be a cakewalk compared to conflict on the Korean peninsula, no matter what Graham and the president may think. The possibility of military confrontation makes it more important that the summit succeed. But even failure would not warrant unleashing the dogs of war, which would result in the worst horrors imaginable.

Doug Bandow is a senior fellow at the Cato Institute and a former special assistant to President Ronald Reagan. He is author of Tripwire: Korea and U.S. Foreign Policy in a Changed World and co-author of The Korean Conundrum: America’s Troubled Relations with North and South Korea.

Sourse: theamericanconservative.com