This article is part of a series of articles titled

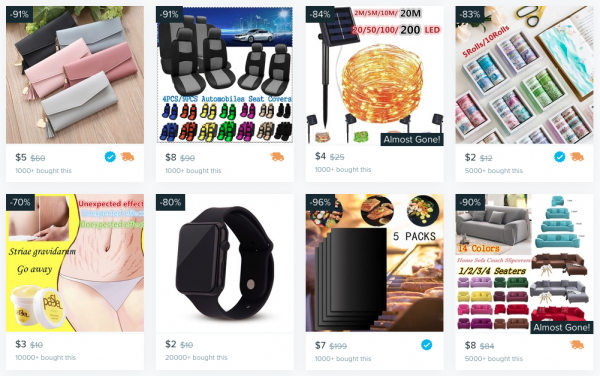

Open the shopping app Wish and you’ll be greeted by a vast array of stuff you don’t need: 12-foot-long pool floaties, whimsical toilet brush holders shaped like cherries and swans, a T-shirt with a photo of the Hanson Brothers above the word “Nirvana,” and at least a few dozen varieties of cord organizers.

Or at least, that’s what I see. Depending on your shopping proclivities and personal demographics, you may find a collection of Bluetooth headphones, children’s pajamas, cooking utensils, or sex toys — almost all of it sold at outrageously cheap prices: $9 for a set of knives, $5 for a T-shirt. Those AirPod knockoffs? Free with $3 shipping. Most of these prices are presented as 80 or 90 percent off their original price, so it seems like you’re getting a discount.

In exchange for these bargains, Wish demands patience. Most delivery estimates range from two to four weeks, giving the marketplace’s vendors time to ship their products from countries like China, Myanmar, and Indonesia. And apparently, even in the age of free one-day shipping, patience is a thing a shockingly large number of people still have.

Last year, Wish says it saw revenue double from the year prior, to $1.9 billion; the company earns money by taking a 15 percent cut of each sale and, to a lesser extent, collecting fees from sellers in exchange for promoting their products. It has raised $1.3 billion since it was founded in 2011, and at its last funding round in 2017, was valued at more than $8.7 billion. It was also the world’s most-downloaded e-commerce app of 2018, with 161 million installs globally, according to app analytics firm Sensor Tower.

Yet compared with other major marketplaces — Amazon (134 million installs last year, for comparison), Alibaba’s AliExpress, eBay — Wish is hardly a household name. It only started selling merchandise in 2013, for one, before which it more closely resembled Pinterest, offering users the chance to create “wish lists” of products pulled from around the web, along with images they uploaded themselves.

By the time it launched e-commerce, it had 500,000 daily users, Wish’s co-founder and CEO Peter Szulczewski told All Things Digital at the time. Its biggest vendors were Chinese wholesalers, and as the company grew, it directed its efforts toward the products that were selling fastest: inexpensive women’s clothing, consumer electronics, jewelry, and accessories — all of which are still among Wish’s top-selling categories. (The company also now has four category-specific apps — Geek, Home, Mama, and Cute — but says they aren’t a significant part of the business.)

Marketing toward lower-income customers wasn’t part of the original business plan, says Tarek Fahmy, a Wish engineering executive, who joined the company in 2012, but as it saw that customers were prioritizing price above all else, “we recognized that this was a significantly underserved market, especially when it came to e-commerce.” Venture capitalists were initially less convinced. “Despite our metrics, we were told repeatedly and at every stage by Menlo Park investors that they didn’t know anyone that would shop on Wish,” Szulczewski wrote in a 2016 Medium post comparing the startup’s rise to Donald Trump’s surprise presidential victory. (In both cases, he argued, elites ignored “the invisible half.”)

The company found this swath of the population — and bargain-hunters from higher income brackets, too — on social media and via search, where until fairly recently it spent the vast majority of its marketing budget on targeted advertising. At this, it excelled, leveraging Szulczewski’s expertise from his years at Google, where he worked on the tech giant’s advertising algorithms.

Most people who discovered the app in its early years did so through Facebook and Instagram, where it still regularly ranks among the platforms’ top advertisers. There, amid endless hyper-targeted campaigns, its ads have become notorious for their occasional weirdness, thanks to an algorithm that pulls in some of the most confounding products from Wish’s catalog of 200 million items: adult diapers with an attached rubber hose (?), shapewear … for your face (??), and a $2 pile of what appears to be worms (???). There are no product labels on most of these ads, so you have to click over to Wish.com — or download the app on mobile — to find out what you’re looking at.

“It’s definitely a marketing tactic,” says Wish’s head of communications Glenn Lehrman. “We like to say that there’s something for everyone on Wish, and I think what makes the site accessible is the fact that it’s fun.”

While some might question whether “fun” is the right descriptor for a strange, phallic-looking object appearing in their Facebook feed, there’s no doubt that the ads — which the company runs alongside more predictable ones for products like clothing and electronics — are getting people’s attention.

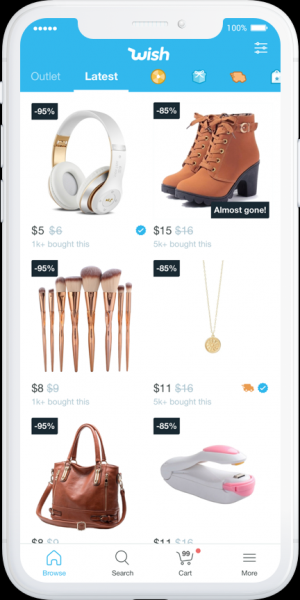

Once they’ve downloaded the app, Wish users scroll through the app for an average of 20 minutes per day, Lehrman says. Unlike most of its competitors, Wish is resolutely mobile-first, taking cues from Instagram’s infinite feed and popular gaming apps with elements like a daily “Blitz Buy” wheel users can spin to unlock limited-time deals and pop-ups that promise further unspecified discounts if shoppers add an item to their cart.

Despite this very modern frame of reference, the concept for Wish actually comes from something far more old-school: the mall. The app was designed to mimic the experience of wandering and getting lost in a place filled with stuff to buy as far as the eye can see, a direct repudiation of the type of search-first purchase behavior encouraged by Amazon and other online retailers.

When the team was building Wish, says Fahmy, “the big players in e-commerce were focused on an intent- and utility-based approach to shopping, which is why you typically see their experiences built around the search bar.” By contrast, only about 15 to 20 percent of Wish transactions begin with a search query, and the landing tab skews strongly toward visual elements (so much so that users don’t even see a product’s title until they click on it).

Fahmy justifies this choice by returning to the mall metaphor — after all, stores don’t necessarily put descriptive signs next to every product they carry. Still, you’re more likely to find context cues walking down an aisle at Target than scrolling down your Wish feed: bath towels are stocked next to bed sheets and pillows, not bike locks or drill bits.

Combined with the recommendation algorithm, this tactic can have unintended consequences. “If the picture is vague or you don’t know what it is, you click there for clarity,” says Mikee Ames, a Wish shopper in Calgary, Alberta. “Suddenly, your browsing algorithm changes and you’re flooded with that genre of item. Ergo, be careful when curiosity about that butt plug gets you because next you’re looking at a whole stream of sex toys.”

Ames works in theater and has used the app to source props for performances, but says her favorite purchases have been for herself: a ramen noodle hoodie (“it’s just so silly and it makes people smile when I wear it out”) and a pair of knee-high socks with a chicken-leg print (“a frickin’ riot”). She prefers Wish to eBay because the refund process is more straightforward (on eBay, shoppers have to request refunds from individual sellers, whereas on Wish they’re handled by a centralized customer service department), though she’s careful to check measurements and read reviews.

Lehrman says Wish gets 500,000 reviews per day from users. According to e-commerce data firm Marketplace Pulse, it surpasses Amazon and other comparable shopping sites in this respect — even with far fewer products and a fraction of Amazon’s total sales — by using emails and push notifications to prompt shoppers to leave feedback. Its communication tactics are tenacious: Within 48 hours of signing up for an account, I received four marketing emails pushing one-hour-only discounts, a shop-more-save-more rewards program, $1 watches, and $10 fitness trackers. For the sake of my inbox (and my sanity), I switched my settings.

”Wish has replaced loyalty with targeted reengagement,” says Juozas Kaziukėnas, founder of Marketplace Pulse. While there may not be 100 million members paying $119 per year to come to the app to stock up on everything from groceries to books to paper towels à la Amazon Prime, Wish says that more than half of customers return for a second purchase. What the company hopes to work on now is building brand awareness, in part through having executives attend high-profile industry events and speak with the press. (Lehrman joined the company in October, before which Wish didn’t have a communications team.)

”Because we have largely traditionally reached people through Facebook advertising, [customers] have been more product-focused than brand-focused,” Lehrman says. “We want people to create more of a relationship with Wish so that they know they can come back here whenever they want to either find that weird, quirky, fun product or something that they feel like they were looking for a great value on.” He also wants to dispel the idea that the marketplace only carries items you can get for a couple of bucks: its top vendor in the US is one that sells refurbished electronics like $100 iPad Minis and $300 HP laptops.

The company’s latest expansion is into products from recognizable brands: Kraft has come on board to sell ketchup and other non-perishable food items, and this summer, Wish will launch a feature which allows users to sort by specific brands and categories for the first time (currently, only general categories like “fashion” and “hobbies” are available).

Wish is also building a team of buyers who will focus on acquiring distressed name-brand inventory to sell on the site — particularly in women’s fashion — in an attempt to compete with off-price retailers like T.J. Maxx and Ross Stores. Eventually it hopes to have a selection that looks like a cross between these chains and its closest physical counterpart, the dollar store, the most successful of which now carry name-brand groceries and household goods along with cheaper knick-knacks and unbranded goods.

”Over time, we hope to evolve to be able to offer everything,” Lehrman says. It will have to tackle logistics concerns like expiration dates and shipping requirements before it gets into groceries, he says, “but we are starting to dabble in it. We haven’t gotten as far down the road yet as, say, toilet paper and paper towels, which I know are pretty popular at places like the dollar stores. But I think over time we will absolutely get there.”

Not coincidentally, dollar stores and off-price retailers are two of the rare current success stories in the retail industry. As mid-priced merchants and department stores have been gouged by declining foot traffic and online competition, the number of dollar stores in the country has swelled from around 20,000 in 2011 to close to 30,000 today, according to the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. TJX Companies, which owns T.J. Maxx, Marshalls, and HomeGoods, generated $39 billion in sales last year and recently increased its store count to 4,381.

What’s notable, though, is that both sectors are primarily driven by brick-and-mortar, rather than e-commerce — which could be either an opportunity for Wish or a red flag. Flash sale sites were the closest online analog to off-price stores during their decade-ago heyday, adding an element of urgency through limited-time promotions that could sell out in minutes. But most of the biggest players, including Gilt Groupe, Rue La La, and HauteLook, have since fallen far, as it has become increasingly difficult to find differentiated products and sell them at a profit. The implosion of Fab.com, a design-focused flash sale site, from a $1 billion valuation to reported $15 million fire sale in 2014 remains a cautionary tale throughout the industry.

Sucharita Kodali, an e-commerce and retail analyst at the market research firm Forrester, says there’s a reason the off-price model isn’t prevalent online: It’s very hard to make it work. “First of all, there isn’t access to a ton of brands to begin with,” she says, pointing to the competitiveness of the space. Flash sale sites “tried to get as much of that inventory as they could, and there just wasn’t enough of it to make a huge, huge business.” Also — as anyone who has sold their stuff on sites like eBay or Poshmark knows — e-commerce demands a lot more legwork in terms of cataloguing, photographing, and keeping track of every last piece of inventory you carry.

As Wish moves into the name-brand space, it will have to make some changes on the back end to cater to Western merchants, including tweaking some of its policies on returns and fraud detection, and updating its seller portal to allow vendors to add elements like barcodes and extra technical specs for electronics. Currently, according to Marketplace Pulse, 87 percent of the app’s 139 million active merchants are based in China, with an additional 7 percent in the US, and less than 1 percent in the UK and Canada. The company doesn’t break out the geographic distribution of its sellers or its customers, but says the US is its largest market (according to Recode, American customers account for 30 percent of its sales), while Europe does more sales overall.

It has been able to maintain its rock-bottom prices thanks in part to a 2011 agreement between China Post and the US Postal Service that sets special rates on shipments from China weighing 4.4 pounds or less. It often costs less to ship these “ePackets” across the ocean than it does to ship a small parcel from one state to another, making already-inexpensive Chinese-made products look even more attractive to American consumers.

This deal might not be long for the world, however. President Donald Trump announced in October that he would withdraw the US from the 145-year-old Universal Postal Union, the United Nations organization that governs the international mail system. In Trump’s view (and that of many others dating back to the Reagan administration), the current arrangement gives China an unfair advantage because it classifies it as a developing country, keeping its shipping rates to the US artificially low.

The withdrawal gives the US a year to renegotiate the terms of the deal — including, likely, setting higher rates on inbound mail from China — and if successful, it says it will stay in the organization. But without the shipping discounts, Wish vendors may have to raise prices.

Lehrman declined to speculate on the potential fallout if rates go up, but says it is something the company has been thinking about for years. It’s investing in local warehousing in the US and Europe to support its Wish Express program, which has enabled shipping times to be cut down to less than a week for certain popular products, though shipping costs vary widely vendor to vendor. (Currently, only about 30 percent of its US shipments are handled by these warehouses, according to Recode.) It is also seeking out more local vendors near its biggest markets.

Szulczewski recently told Forbes that the company is planning for an IPO within the next year or two. It is looking to Latin American markets — Mexico, Argentina, Chile — for growth, and eventually Africa when the logistics infrastructure catches up, Lehrman says. Before it can tackle global domination, though, there are a few things it needs to take care of at home.

For one, there’s the reputation issue. While its overall ratings on Google Play and Apple’s App Store are high — 4.3 out of 5 for 7.9 million reviews and 4.7 out of 5 for 885,000 reviews, respectively — many of the reviews marked “most helpful” by users describe nightmarish experiences with shipping and customer service: items that haven’t arrived after months, impossible-to-obtain refunds, unauthorized purchases after using a credit card on the site. Sites like Trustpilot, Better Business Bureau, and Complaints Board are littered with one-star ratings for the company. Last year, Wish settled a class action lawsuit alleging that it duped customers by inflating the “original” prices of products on the site to make the deals look better than they were. It did not admit any wrongdoing, but agreed to pay between $3 and $20 to US customers who purchased from the site within a four-year timeframe, plus more than $2 million in legal fees.

On the app itself, Wish uses customer reviews to establish trust, but like Amazon — and, frankly, most marketplaces — Wish says it is constantly fighting fake reviews. Last year, it noticed merchants gaming the system by using algorithms to plug in four- and five-star reviews, so it developed its own algorithm to try to weed out the ones with suspicious phrasing. A newer version also flags products that get a suspiciously high share of one- or two-star ratings.

Lehrman also says the team is “extremely vigilant about ensuring that counterfeit items don’t show up on the site” and will take down any fakes they’re notified of by brands. But it only takes a quick search to find items like $12 Gucci knockoff belts and $15 Adidas Yeezy lookalikes. (It should be noted that much the same is true of Amazon and eBay.)

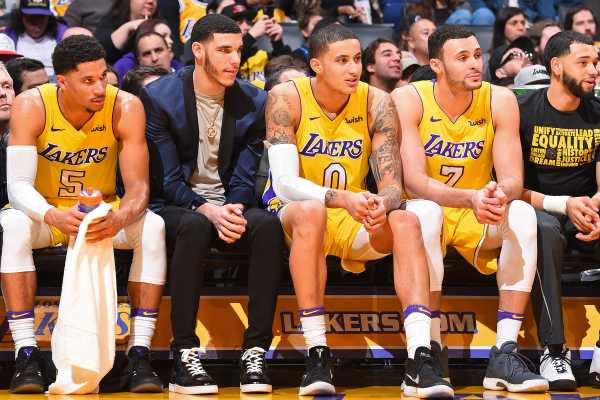

Wish is a private company, so its numbers are self-reported, and it may take an IPO — and the scrutiny that comes with it — for skeptics to be convinced of the viability of its business model. It is not currently profitable, as it continues to spend heavily on marketing. In late 2017, it announced a three-year, $30 million sponsorship deal with the LA Lakers (its logo is now on the jerseys), and last year, it tapped seven of the world’s most famous soccer stars for a campaign that ran during the World Cup. It’s also still spending big on targeted ads: In January, according to Sensor Tower, it ranked first for ad impressions on both Facebook and Instagram, and its Facebook page shows around 21,000 active campaigns in the US alone.

Kodali is dubious this tactic will be effective for long. “If they keep advertising on Facebook, maybe they keep getting new customers,” she says. “But at some point you’ve cycled through everybody who’s got a proclivity to buy with you, and customer acquisition just gets harder and harder.”

Lehrman says the company is moving toward a more balanced mix of marketing channels. A few weeks ago, it launched its latest ad: a one-minute online spot comparing Wish to a fever that’s spread around the world, transfixing shoppers with $28 drones and $5 cat costumes. “Inside this building,” the narrator reads as the camera zooms in on the company’s San Francisco headquarters, “software geniuses had transformed the very nature of shopping. And what they’d done was glorious.” Now, he says, $5 could buy a pair of sneakers, a leopard print coat, or a nonstick frying pan.

What he doesn’t mention is that after plenty of scrolling, the only $5 pan I could find was less than five inches wide and that many of the leopard print coats appear to be more like cardigans once you flip past the paparazzi-esque model photos. He isn’t wrong about the sneakers, though. One $5 pair even has five stars.

Sourse: vox.com