In 2012, Rolling Stone produced a list of the 10 K-pop bands most likely to make it big in the US. Achieving significant US fame was a newly attainable, if still distant, milestone for South Korean pop groups thanks to the 2000s’ tremendous exporting of South Korean culture overseas — a trend known as Hallyu, the Korean Wave. Rolling Stone’s list, which appeared two months before Psy’s “Gangnam Style,” included groups like Big Bang, Girls’ Generation, and 2NE1 — the greatest bands of what’s generally thought of as the “second generation” of pop groups to emerge during K-pop’s rise to international prominence.

It didn’t, however, include a group of teenage boys, recently assembled through a studio audition process, who were being meticulously polished and prepped for their debut. On December 22, 2012, the group released a number of Soundcloud clips featuring its seven members rapping in Korean and English — including a rap cover of Wham’s “Last Christmas.”

It was hardly the stuff of attention-getting Korean hip-hop. But the band in question — Bangtan Boys, later officially known as BTS — would go on to completely transform the image of all-male boy bands in South Korean music and shatter conceptions of what breakout success looked like for South Korean bands overseas.

Related

How K-pop became a global phenomenon

BTS’s US prominence has expanded rapidly over the past year, when the band seemed to smash one success metric after another, from spending multiple weeks on US charts to a landmark appearance at the American Music Awards to collaborating with Steve Aoki for their December single remix “Mic Drop.”

BTS is currently celebrating a truly unprecedented year. They’re the first South Korean band in history to debut an album at No. 1 on the US Billboard chart, as well as the first with a single at No. 10 on the Billboard Hot 100. The band’s world tour promptly sold out. They’ve released two follow-ups to 2017’s Love Yourself: Her; the first, Love Yourself: Tear, moved 135,000 units in its first week to land atop the charts. Now, they’ve released the final installment of their Love Yourself trilogy — Love Yourself: Answer, an effusive double album featuring a string of their recent hits and one huge collaboration: Queen Nicki Minaj joins them for a classic mic-drop guest verse on a new version of their song “Idol.”

Why was BTS the band that finally broke through the culture barrier overseas to make significant waves in the US? The answer lies in a combination of factors, and most of them are about change: the changing nature of K-pop’s studio culture and the way “idols” are produced; changing depictions of masculinity in South Korea; changing ranges of acceptable expression in K-pop; and, above all, the approach BTS took to building its fan base and interacting with its fans.

But to understand all this change, we have to back up a few years to understand how K-pop became the regimented industry it is today — and how BTS subverts that regimen.

How did K-pop become a $5 billion global industry?

We explore the elaborate music videos, adoring fans, and killer choreography for Explained, our weekly show on Netflix.

Watch now on Netflix.

BTS is the product of an industry insider who wanted to create a new kind of idol

K-pop began on April 11, 1992, when a hip-hop trio called Seo Taiji and Boys performed in a talent show on a national South Korean network. Seo Taiji and Boys were innovators who challenged norms around musical styles, song topics, fashion, and censorship, which was unprecedented for a culture whose musical production had spent the past few decades subjected to strict government oversight. But it wouldn’t last.

In the ’90s, three powerhouse music studios began cultivating what would become known as idol groups. Assembled through auditions and years of grooming within an intense studio culture — the highly regimented system of idol group production in Korean and Japanese music studios — idol groups are polished to perfection, designed to present the very highest standards of beauty, dance, and musicality. Children who enter these studios spend most of their lives enduring rigorous training to become part of an idol group. If they’re chosen, the studio exerts a huge amount of control, not only over the songs they sing and the way their band is marketed but also over their daily lives.

Idol groups have come to dominate the Korean music industry, but there are well-known toxic and abusive elements of studio culture — as revealed by the recent death by suicide of Shinee artist Kim Jong-hyun. Studios systematically ironed out most of the personal expression and socially conscious music that Seo Taiji was originally known for — after all, it’s hard to express yourself when you’re contractually forbidden to have a personal life. Typically, idols only feel free to open up about their struggles after their studio careers end.

It was within this environment that a man named Bang Si-hyuk began to quietly build a different kind of studio, and to cultivate the band that would become BTS. A successful songwriter and music producer, Bang was nicknamed “Hitman” for writing a string of popular songs, from g.o.d.’s “One Candle” in 1999 to T-ara’s “Like the First Time” a decade later. He worked as an arranger and producer with the studio JYP until 2005, when he left to form his own Big Hit Entertainment.

But Bang also struggled with his position within the industry. As a studio owner, he confessed to insecurity about his work and said he admired singers who could express their personalities in their music. This combination of ideas — the honest musical expression of one’s creative anxieties — would become a crucial element of BTS.

In 2010, Bang began to assemble a group of teens for a group he called the Bulletproof Boy Scouts. This would go on to become Bangtan Boys, then BTS, but the ingredients of their success were inherent in the original name. Bang intended “bulletproof” to function as a celebration of the kids’ toughness and ability to withstand the pressures of the world. But he also wanted the band to be able to be sincere and genuine — not immaculate idols groomed amid studio culture, but real boys who shared their authentic personalities and talents with the world.

This approach is quite different from the normal studio approach to idoldom, wherein idols are trained to be pleasant but mild — to be blank slates upon which viewers can project their fantasies. By contrast, Bang wanted BTS to be full of figures that audiences could relate to. In a 2018 interview with the South Korean newspaper JoongAng, he described how he originally thought of BTS as consisting of gentle, sympathetic idols who could mentor their fans:

To create that band, Bang had to shake up the established precedents for how idol groups are treated. BTS wouldn’t have strict contracts and curfews, and they’d be allowed to discuss the pressures of stardom. Their lyrics would be open about the cultural pressure placed on Korean teens to excel and do well and to repress their anxieties. In short, they would be frank, honest, and natural.

How they did it: a consciously authentic style combined with socially conscious messaging

“We came together with a common dream to write, dance and produce music that reflects our musical backgrounds as well as our life values of acceptance, vulnerability and being successful,” said BTS’s leader, RM, in a 2017 interview with Time. There are six main ways BTS breaks with established precedent for K-pop boy bands to carry out this mission:

It should be noted that most of these elements have been present in numerous other recent K-pop groups — most notably Big Bang, which probably influenced BTS more than any other K-pop group. What Big Hit Entertainment did, however, was to systematize these elements in BTS, and market them hard.

In the earliest videos of the band, from the months before their 2013 debut, the members were styled as young and sweetly innocent, maintaining the common “schoolboy” concept of male K-pop idol groups. When the group officially launched in June 2013, however, it was with a hard style paying homage to old-school gangster rap. Their first single, “No More Dream,” was an ode to teen apathy, a rebellious rejection of Korean traditionalism.

And it wasn’t exactly popular: Early audience reactions included a lot of eye-rolling at what was viewed as a superimposed gangster image that the band hadn’t earned. And while the band was clearly leaning on the confessional lyrical apathy of Seo Taiji and his early successors, it all seemed contrived rather than real.

A K-pop commentator who goes by the mononym Stephen ran a weekly podcast, This Week in K-Pop, from 2013 to 2017, which chronicled new releases in K-pop and inevitably documented the rise of BTS. But Stephen and his co-hosts were initially skeptical of the band. “Now K-pop has faux hip-hop undertones everywhere,” he said. “But in 2013 there wasn’t really that much, other than Big Bang. So when [BTS] came out with this very in-your-face, ‘We’re hip-hop’ image, it felt a little silly.”

Stephen pointed out that K-pop in general suffers from this problem. “K-pop really likes the look and attitude of hip-hop, but not too much. It’s very surface-level: hip-hop as a culture rather than as a musical genre.”

BTS’s climb to success, then, involved the band finding a way to communicate that this confessional image was real. They did this by mixing their openness on social media with blunt and honest lyrics — and owning their status as an underdog group battling to succeed against other bands who came from established studios with larger budgets. They spoke openly of the influence of Big Bang, a hip-hop group that’s also known for its socially conscious messaging. And they covered Seo Taiji’s ”Come Back Home”:

In essence, they found a way to imbue their musical style with substance. This led to well-reviewed, pointedly personal works like their three-album series The Most Beautiful Moment in Life, which deftly mixed “theater [and] autobiography.”

Their two most successful singles from this period managed to neatly encompass this new direction. “I Need U” was a refreshing, personalizing step away from hip-hop toward an R&B sound, while “Dope” openly celebrated the endless grind of their lives: “Over half of the day, we drown in work / Even if our youth rots in the studio / Thanks to that, we’re closer to success.”

“Dope” also drew attention to the band’s talent in a major way: It was the moment South Korea realized that these boys could dance.

“‘Dope’ is probably my favorite video of all time,” Stephen said. “Focusing on dancing like that — they weren’t the only ones doing it, but they were definitely the best ones doing it.”

“And they alternate,” he added. “They do the big, boisterous, in-your-face dance video. But they also do those more emotional mini-art-flick type videos.” And no BTS art flick is better than “Blood Sweat & Tears,” the gothic, gorgeous 2016 single that launched them into a new level of international fame.

Colette Bennett is an entertainment reporter and a huge fan of BTS (she’s seen them in concert four times since 2014), but even though she liked their music, it took a while for her to take their message seriously.

“When The Most Beautiful Moment in Life series started, I saw something,” she told me. “And that’s when I went back and watched their old vlogs. Up to and after debut, [these] skinny kids all crammed in a studio the size of a broom closet. Just … being honest about how much they poured into what they were doing, humble about being scared and unsure, etc.”

To Bennett, the band’s frank discussion of mental health and the expectations placed on Asian teens was revolutionary. In 2016, she wrote a profile of the band that argued that they were changing the nature of K-pop through their interpersonal approach to image-making. While watching them on their 2017 “Wings” tour, she said, “there was a moment that really stuck out.”

“There’s a song the three rappers do called Cypher 4. The refrain is, ‘I love, I love, I love myself / I know, I know, I know myself.’

“I looked around me at hundreds of people in their 20s cheering every word, and I thought, ‘My god. They’re using their influence to teach young people — the ones most inclined to grapple with self-hatred — to start considering what self-love means.’”

The BTS ARMY is real, and it is mighty

BTS’s fans — who collectively gained the nickname ARMY for their well-organized and loyal response to the group — responded to that confessional strategy so well that by 2015, tickets for the band’s sold-out limited US tour were reportedly being scalped for more than $10,000. Tickets for their current sold-out tour are in high demand, with an average price of $452, the most expensive of the summer.

Stephen told me that it took a while for the hosts of This Week in K-Pop to realize how big BTS had gotten. “We always thought the next big group to cross over would be a girl group, somebody like Twice,” he told me. “I don’t think it really hit me how big they were until I moved to Korea in 2014 and talked to the children. Every single person in my school system, from teachers to high school students to middle school students to elementary — everybody knew who BTS was.”

BTS’s international fandom was also hard at work making sure the band had a chance to break through. Throughout 2017, fans systematically bombarded North American retailers like Walmart, Target, and Amazon with pleas to stock BTS’s new albums — and then promptly pushed the albums up the sales charts. The ARMY was so mighty that by the time BTS made their US television debut at the American Music Awards in 2017, the audience was treated to a time-honored K-pop spectacle: an auditorium ringing with fan chants.

The international BTS fandom has worked to mainstream K-pop as few other factors have. On Tumblr, the internet’s unofficial home for fandom communities, BTS and its members reign supreme, recalling the vast reach of One Direction in its heyday. In April 2018, Tumblr decided to stop breaking out K-pop as a separate category in its popular weekly Fandom Metrics, an official Tumblr product that measures the popularity of fandoms and related subtopics across the site. By merging K-pop with English-language groups, the account could more accurately reflect the relative popularity of K-pop bands to their Western counterparts.

The first week the categories merged, BTS debuted at No. 1 on the platform, ahead of Beyoncé and Harry Styles.

So who are these guys, anyway?

Bang’s initial idea for BTS was to build not a boy band, but rather a supporting crew around one talented teen: Kim Nam-joon, a.k.a. RM. He quickly opted to go the idol group route instead, and it took nearly three years of trying out different combinations of members and styles for the boy band to finally emerge.

Most K-pop groups have band members who occupy fixed, noticeable positions within the band: the leader, the public “face” of the group, the “visual,” whose main role is to be pretty, and so forth. Not every group has set roles, and most roles change over time. And because BTS is trying to be less staged than other groups, its roles are a lot blurrier than other groups. Still, there are a few constants:

The leader and lead rapper: RM

Born Kim Nam-joon, RM is a 23-year-old rapper and the first member recruited to BTS. It’s not exaggerating to say that the entire band was built around him.

RM first made his name as an underground rapper; still in his teens, he was frequently spotted spitting verses alongside his friend Zico, who would go on to become the leader of the K-pop group Block B. After a friend told Bang about the rapping teen, Bang recruited him into his studio, where fans gave him the pre-debut nickname “Rap Monster.” From there, the idea to form an entire idol group rapidly took shape, and the Monster shortened his stage name to RM.

The dancer/rapper: J-Hope

Jung Hoseok, a.k.a. J-Hope, sometimes called Hobi, is most frequently described by fans as a ray of sunshine, thanks to his sweet personality. The 24-year-old is one of the group’s main songwriters as well as a frequent choreographer, its lead dancer, and one of its three main rappers. Since joining the group, he’s had a notable solo debut that landed him in the top 40 on the Billboard 200. And have I mentioned his chin could cut glass?

The vocalist/dancer: Jimin

No single member of BTS is its “face,” but the spotlight often belongs to 22-year-old singer and dancer Park Jimin. Jimin is frequently positioned as the group’s lead vocalist. He’s also one of the group’s three main dancers, for good reason, along with J-Hope and Jungkook, and one of its most popular members.

The mentor vocalist: Jin

The 25-year-old Kim Seokjin, a.k.a. Jin, is the group’s oldest member, and as such he frequently occupies a mentorship role within the group (complete with dad jokes). He’s one of the group’s main vocalists, and though he’s not officially the group’s “visual,” he seems to have a habit of accidentally going viral for being beautiful.

The prodigy: Jungkook

Depending on when and whom you ask, Jeon Jungkook is either the designated “face” of the group, the designated beauty, the designated main singer, the group’s centerpiece member, or all of the above. But there’s one role that never changes: At 20, he’s the youngest. The group often calls him the “golden maknae,” a.k.a. the golden child, because he’s a bit of a wunderkind in terms of talent. In fact, he was in high demand before he settled on joining Big Hit because he looked up to RM. But he’s unquestionably the baby of the group — and arguably its most popular member.

The rapper: Suga

Min Yoongi, stage name Suga, is one of the group’s three rappers. At 25, he’s also one of the oldest members, which makes him something of a group dad. His name comes from his preferred basketball position of shooting guard, but legend has it that Bang chose the name for him because it reflects his “sugary” personality — subtle, yet sweet and generous.

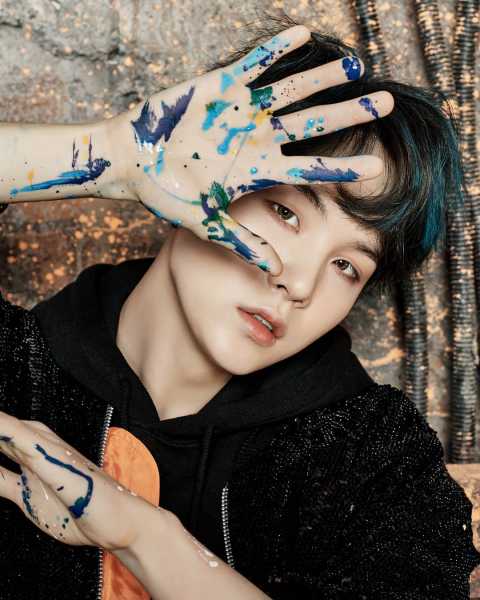

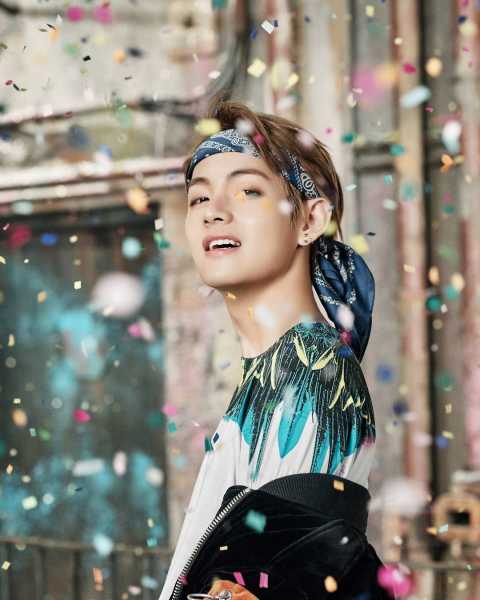

The vocalist/dancer: V

The 22-year-old Kim Taehyung chose the stage name “V” for victory — but it could just as easily stand for “versatile”: He’s one of the vocalists, he often joins in on the dance line, and he’s even tried his hand at rapping. His playful, quirky personality (let’s call it “singular”) and penchant for stealing the spotlight have made him one of the group’s most popular members. It also probably doesn’t hurt that he has chemistry with everything that moves.

Which reminds us: We can’t talk about boy bands in modern fandom without talking at least a little about shipping. BTS’s popularity lends itself to RPF (real-person fiction) shipping among the band members. And no wonder: The internet is teeming with gigabytes of media in which the members of BTS display zero interpersonal boundaries, are physically affectionate, and generally behave in playful, intimate ways that deconstruct heteronormative masculinity.

Again, they’re by no means the first band to do this: Boy bands in both Korea and Japan have spent decades being marketed with homoerotic appeal, and normal interactions between Korean men can read as transgressive of heteromasculine norms in English-language cultures. One Direction notoriously followed in the wake of these many groups by practicing a similar transgressive physical intimacy; in that fandom, Larry Stylinson shippers in particular essentially codified for the ARMY how to micro-analyze body language, onstage and off.

While BTS are experts at teasing homoeroticism in their videos, they’re also experts at evading questions of shipping — though in fandom, you can find every ship permutation there is. Most BTS shipping is pretty evenly split between four pairings: Yoonmin (Suga/Jimin); Taekook (V/Jungkook); Jikook (Jimin/Jungkook); and Vmin (V/Jimin).

But there’s one ship that rules all, and that’s the relationship between band members and the ARMY itself. Crucial to the band’s success is its members’ ability to directly communicate their love and affection to fans. And honestly, grabbing and holding the attention of so many international fans, despite considerable language and cultural barriers to entry into the fandom, is an achievement by itself. In that respect, BTS may be truly a K-pop revelation.

A lot of this may be hype, but it’s important for K-pop’s legacy

Then again, not everything about BTS is a phenomenon. Understanding its rise to the top also means acknowledging that it’s not alone in its class: It’s succeeded and grown alongside other bands that are also innovating and reaching new levels of international success. Collectively, this K-pop generation is rapidly changing the conversation and pushing the limits of what K-pop is allowed to be.

“If you were to be like, ‘Who’s the realest K-pop band,’ I’d be like, ‘… None of them?’” Stephen said. “I personally think you need to be popular first in order to be seen as authentic.” He pointed out that other recent groups, like AoA, also had to work very hard before achieving rapid success. “I think every K-pop group talks about how hard they struggle,” he said. “But when it’s a very popular group, it becomes a better story and a better sound bite.”

Still, in the wake of the December suicide of Shinee member Jong-hyun, the industry as a whole — and BTS in particular — has been vocal about the need for honesty and openness about the pressures of the industry.

Stephen told me there’s a real core appeal in what BTS is doing. “A lot of their ballads really do sound like they’re talking to you and confessing to you, more so than a lot of pop standards,” he said. “And they’re definitely among the hardest-working K-pop groups.”

But to Stephen, the real lesson of BTS’s success isn’t about the band’s ability to transcend the norms of K-pop; it’s about K-pop’s rapid ascension into the mainstream.

“I’m sure there are millions of One Direction fans who thought they were the first of their kind,” he said. “Whereas an older fan might have been like, hello, NSYNC?

“I think if you were to ask somebody who was into K-pop during Big Bang’s peak, they would be like, ‘BTS is nothing new.’ But if you ask the newer generation that wasn’t familiar with Big Bang, they’ve never really experienced that 0-to-100 rise of a group before, until now with BTS. So it feels new to them. I think that shows how generational K-pop is, and how far it’s come in such a short amount of time.”

And, as Stephen noted, BTS’s international success has been landmark, even if it’s been built on giant shoulders. “Is it groundbreaking? Definitely not. But they definitely raised the bar for K-pop.” And that validates fans’ enthusiasm in a major way.

“And once you have a fan’s heart,” he added, “you have their loyalty.”

Sourse: vox.com