“`html

Recently, Zohran Mamdani stated that, if victorious in the mayoral election this autumn, he intends to terminate New York City’s “gifted and talented” program for children in kindergarten.

This decision sparked considerable controversy. Andrew Cuomo, Mamdani’s primary adversary in the mayoral race, criticized the progressive candidate’s proposition as “devastating.” According to Cuomo, when a municipality does away with distinct classrooms for its most intellectually advanced 5-year-olds, “the sole chance your offspring has of receiving a truly superior education in public schools vanishes.”

The Washington Post’s opinion writers similarly disapproved of Mamdani’s stance, dismissing it as a strategy to “hinder bright students in the name of fairness.”

Such critiques are overstated. It is rather uncommon for educational institutions to classify pupils by aptitude at the kindergarten level. By ending such practice, New York City would not be adopting an original, socialist-leaning tactic. In contrast, Mamdani’s existing educational blueprint — which would keep advanced classes starting in the third grade, along with the city’s exclusive high schools — comprises considerably more elaborate schooling than one typically finds in a standard American school system.

Nevertheless, the intensity of Mamdani’s detractors is easy to understand. His declaration arose amid a far broader — and more significant — discussion within the Democratic Party concerning educational guidelines.

For a number of years, certain liberals have strived to limit advanced programs, even in the upper grades. This movement argues that “grouping” — the act of dividing pupils into separate classrooms or schools, according to their scholastic capabilities — worsens racial inequalities, while offering minimal to no advantage to top students. These justifications have prompted a few liberal states and cities to reduce advanced instruction in recent times.

However, “de-grouping” initiatives have shown to be contentious. Moreover, many Democrats have urged their party to give up such strategies and unequivocally endorse grouping, at least in certain grade levels.

On this greater question, I believe the Cuomos of the world are largely accurate. The Democratic Party could potentially foster better educational results for all children — along with its own political objectives — by advocating some forms of ability-based categorization.

Advanced programs often result in racial differences. That doesn’t automatically mean they’re unfair.

Resistance to grouping — both in New York City and elsewhere — has commonly focused on the worry that it maintains racial inequity. Advanced programs and high-level classes tend to disproportionately include white and Asian pupils, while lacking Black and Hispanic ones.

This article originally appeared in The Rebuild.

Sign up here for more articles regarding the lessons progressives should glean from their defeat in the elections — and a closer study of their future trajectory. By senior writer Eric Levitz.

In New York City, to illustrate, 42 percent of public school students are Hispanic, 20 percent are Black, 19 percent are Asian, and 16 percent white. Still, white and Asian pupils represent 75 percent of pupils enrolled in the city’s advanced and talented programs. In the meantime, at New York’s distinguished high schools — which assess applicants by standardized exam — barely 10 percent of acceptance letters this year were given to Black and Hispanic pupils.

To some critics of grouping, any guideline that yields such figures is fundamentally unjust: Significant racial variances, they assert, serve as definitive proof of prejudice.

This viewpoint is understandable. The disparities in New York City’s selective programs are evident and unsettling. And it is valid to be concerned that they might be indicative of biases in the selection procedures. Conceptually, the phrasing of standardized assessments could provide an advantage to pupils from particular cultural backgrounds, unrelated to their academic proficiencies. And racial biases could sway which students teachers nominate for advanced programs.

Furthermore, there is proof that advanced educational schemes in different regions have under-identified gifted pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds, partly by depending on assessments that parents must choose to participate in. It’s therefore crucial to closely examine the impartiality and availability of any grouping program’s screening method.

All the same, there is no justification to assume that a thoroughly unbiased evaluation of student capability would prevent racially unequal results. Conversely, the contrary anticipation derives from a pair of the left’s core beliefs, which are:

- Economic advantage makes it simpler for children to realize their intellectual potential.

- White and Asian households tend to be more financially privileged than Black and Hispanic ones.

Both of these notions are sensible. Of course, a child’s scholastic success isn’t determined by their household’s earnings. Parents can encourage their children’s educational achievement through non-monetary means. And effective schools can nurture the capabilities of impoverished pupils. However, there is both conceptual and factual rationale to think that material advantage supports intellectual growth. In other situations, some organizations critical of grouping emphasize this aspect.

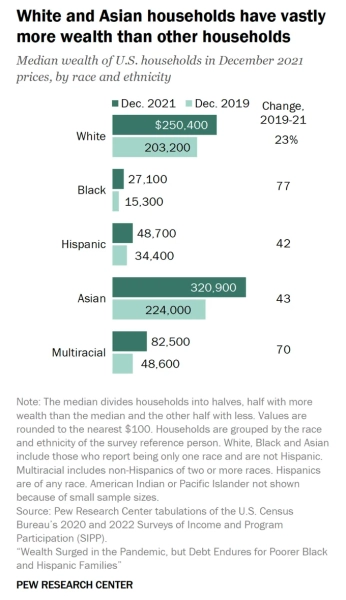

At the same time, it is undeniably accurate that America’s white and Asian populations have greater median incomes and total assets than its Black and Hispanic ones. The median household income among Asian families in 2023 was $112,800 annually; among non-Hispanic white families, it was $89,050; among Hispanic families, it was $65,540; and among Black families, it was $56,490.

Racial differences in affluence follow the identical order but are considerably more extreme:

Consequently, the reality that a gifted program or selective high school has too few Black and Hispanic pupils does not necessarily indicate that its admissions process exhibits racial favoritism. Provided that economic privilege leads to student success — and Black and Hispanic families remain economically deprived — categorizing pupils by aptitude will generate racial differences.

To be reasonable, an individual could reasonably oppose grouping on these specific reasons. To be sure, racial integration is appealing. The reality that sorting by ability renders classrooms less racially varied argues against such sorting.

Even so, it is challenging to contend that schools should give precedence to the racial diversity of their classrooms over the academic achievement of their pupils. If grouping academically assists both those admitted into advanced programs — and those who are not — then it would be difficult to oppose it for reasons of racial equity. In such a scenario, there would definitely be superior methods to encourage integration than de-grouping — strategies that would not compromise all students’ intellectual progress. To begin with, we might attempt to distribute wealth and earnings in a less drastically uneven fashion.

Fundamentally, therefore, the argument against grouping hinges on its effects on student performance, instead of its impacts on classroom demographics.

Related

- What can Democrats glean from Zohran Mamdani’s victory (and what is beyond their grasp)

When implemented properly, grouping can enable every child to attain their potential

There are authentic reasons to be anxious that those consequences could be adverse, specifically for lower-achieving pupils. Children who aren’t chosen for “advanced” programming may endure a loss in confidence. Isolating them from more academically proficient pupils could deprive them of chances to gain knowledge from their fellow students. Moreover, because high-achievers are disproportionately financially fortunate, concentrating them in separate classrooms or schools could in theory give rise to an unjust allocation of resources: Through their considerable political sway or outright contributions, the families of high-achievers might secure improved tools, financing, or instructors for their children’s educational settings.

These hazards would be troubling in any situation. In a world where less advanced pupils disproportionately suffer from racial and economic disadvantages, they are specifically worrisome.

Certain studies, moreover, imply that grouping presents limited benefit to high achievers while causing detriment to less advanced pupils.

Regardless, we possess greater justification to hold the belief that separating pupils by capability is effective for all pupils – when conducted appropriately – than we have to question that notion.

To begin, there is a robust theoretical foundation for supposing that grouping would assist pupils generally, and high achievers particularly. American classrooms are inclined to include students with radically differing aptitudes. A current piece of research indicates that a normal fifth-grade classroom is comprised of pupils who have yet to grasp second-grade mathematics and those who’ve already learned the eighth-grade version.

It is difficult to grasp how this arrangement could be academically ideal. Furnishing instruction that simultaneously presents a challenge to advanced pupils — and benefits struggling ones — seems inherently more complicated than accomplishing either of those tasks individually.

A substantial collection of studies verifies this intuition. A review in 2016 of 100 years of studies regarding ability-based grouping found that advanced programs and diverse other styles of grouping offered advantages to high achievers, intermediate achievers, and low achievers alike. Numerous (though not all) prior meta-analyses — which are analyses of other analyses, to put it another way — have yielded similar results.

In addition, there is evidence that advanced educational schemes can uniquely assist academically gifted Black and Hispanic pupils in attaining their capabilities. A study in 2016 of one sizable metropolitan school district’s advanced or high-achieving program determined that it notably increased mathematics and reading grades for high-achieving Black and Hispanic fourth-graders. These gains came without discernible detriment to pupils who remained in non-advanced classrooms.

At the same time, an experiment performed in more than 100 primary schools in Kenya found that grouping aided lower-achieving pupils by enabling instructors to customize syllabi to their level.

It still remains accurate that not every study of ability-grouping illustrates considerable advantages. However, this might reveal the profoundly variable quality of advanced educational schemes. Simply segregating pupils by aptitude will create minimal impact if instruction isn’t adjusted to fulfill the specific needs of sorted classrooms. Grouping programs in which curricula are substantially modified are inclined to demonstrate favorable results, while those with reduced customization have little advantage.

Related

- The emergent “science of reading” movement, explained

Appeasing affluent white parents carries political importance

Transcending its immediate effects on learning, grouping presents another significant advantage: It can dissuade well-off families from forsaking your public school arrangement.

Strangely, detractors of grouping have at times criticized the practice for performing this duty. The Century Foundation’s Eishika Ahmed writes that, “By failing to resolve equity,” New York City’s advanced and talented program “essentially continues to work as initially designed: as a means to keep [w]hite middle-class families within the public education framework.”

Plainly, this shouldn’t be the singular objective of any educational initiative. Regardless, if Democratic policymakers in New York — or any different key city — desire to optimize the resources at the disposal of disadvantaged pupils, then they must address the educational needs of affluent parents.

The fact is, whenever a high-income family abandons Brooklyn for a more class-separated suburb, this diminishes revenue for the city’s governing body — as a result, the finances available to its public schools. In a less direct manner, middle-class families enrolling their children in private institutions can weaken political backing for school finance. In each scenario, socioeconomic integration declines.

In theory, grouping can assist in preventing these consequences, given that it furnishes wealthy families with a route to gain access to accelerated learning opportunities for their more bright children — while averting the need to quit public schools or move to a privileged suburban vicinity. This does seem to be validated in practice: A recent analysis of Texas public schools determined that districts with elevated levels of grouping have a smaller proportion of pupils enrolled in private schools.

Democrats ought to enhance their image in relation to education

The justification for Democrats to embrace grouping is not merely material but political.

The Democratic Party has customarily held a substantial advantage in regards to the subject of public education. Nevertheless, this edge has dwindled notably in recent years, vanishing completely in some polls. In 2024, the Democratic statistical agency Blue Rose Research discovered that voters narrowly favored the Republican Party on education. A pair of years prior, two independent polls of voters in contentious regions — one conducted by a pro-education reform organization, the other by the American Federation of teachers — each encountered a minor plurality of voters leaning toward the GOP on the issue.

Source: vox.com