Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this storyYou’re reading Critic’s Notebook, our regular weekend piece considering the most compelling occurrences in the cultural climate.

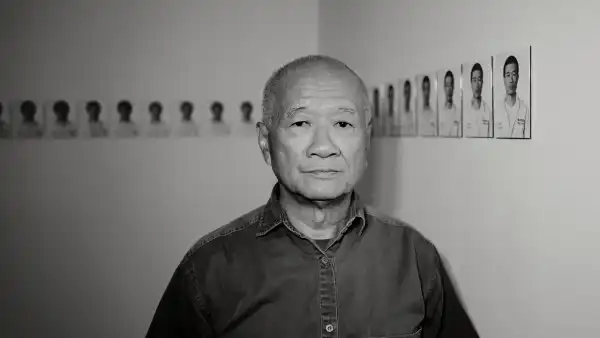

More often than not, passersby halt at a makeshift memorial underneath a raised part of the J and Z lines in North Brooklyn. This behavior is atypical. New York City teems with unfeeling individualists who nevertheless adhere to certain standards very firmly. Upon encountering a memorial during one’s journey, the display of respect is a quickened pace, a simulation of a clear mind, a diverted stare. Yet these individuals are losing themselves; they are coming to a standstill at this one place of mourning because it is a demonstration of something remarkably unsettling: the anguish of young people. Enclosed within the hollow of a steel beam, there are corner-store bouquets, there are flickering candles, and there is a pristine poster, filled with messages crafted in rounded, blocky letters—like notes penned in yearbooks at a graduation ceremony—directed toward the departed, two junior high students, Ebba Morina and Zemfira (Zema) Mukhtarov.

Another dedication is present, a recording. A person grieving posts on social media from the uttermost height of the Williamsburg Bridge, at nightfall. From this aerial perspective, the Manhattan-bound J train, traversing the bridge underneath, appears as a rigid metallic line. The recording is embodying the viewpoint of the metropolis itself on October 4th, the night that Ebba and Zema, clad in somber, obscuring hues, propelled their small bodies onto the top of a subway car, where they were afterward discovered, deceased, at the Marcy Avenue stop. The recording, captured by an individual who must have ascended one of the bridge’s three-hundred-and-ten-foot towers, is essentially a panegyric fashioned in the clutch of the rationale that resulted in the young women’s demises. The speaker, much like Ebba and Zema previously did, uploads clips to social media documenting their ventures into the off-limits areas of New York City’s concrete framework—the underbelly—and thus they might evince an exclusive grasp of the sorrow, a yearning to subvert the common narratives of teenage foolishness or recklessness.

Ebba and Zema were the fourth and fifth persons to meet their end this year while perched on the exterior of a train. Most of the casualties have been youngsters. This trend, recognized as subway surfing, has lately been escalating, leading the Metropolitan Transportation Authority to revitalize its prevention effort—“Ride Inside, Stay Alive”—by enlisting famous individuals such as the vocalist Cardi B and the accomplished BMX cyclist Nigel Sylvester to produce announcements that resonate within subway stations and select trains. (“Stop subway surfing!” Cardi states. “Ride safe, keep it cute, and keep it moving.”)

“Ride Inside, Stay Alive” was initiated in the spring of 2023, responding to an upsurge in surfing fatalities. Mayor Eric Adams conducted a press briefing beneath an underpass on the 7 train in Queens, a line that is largely elevated, until the East River. That line, along with the J, M, and Z, had been designated by the M.T.A. and New York Police Department as an “overwhelming location” for surfing. The authorities themselves employ the terminology of “surfing,” despoiling the lingo. Akin to the Rudy Giuliani mayoralty, yet somewhat feeble in ruthlessness, the Adams government has been eager to identify an affliction, a chance to conjure up fundamental scares of societal failure that the mayor’s administration can then assert to remedy. At the time, outer-borough New Yorkers were seething at Adams, who had reneged on his promise to be a “bus mayor.” (Buses have actually decelerated during his administration.) Here existed a transit predicament he hadn’t triggered, one that could be rectified. Here existed a transit predicament that could be pinned on children.

Are thrill-seeking youths akin to avians, deterred by illustrative spikes on the rooftop? In late October, the M.T.A. did affix barricades—upright cushions constructed of rigid rubber—in between cars on certain trains operating on the 7 line, confining ascent paths. These trials in configuration cannot conceal the actuality that the concern has largely been delegated to the constabulary. This year, the N.Y.P.D. has apprehended more than one hundred and twenty individuals on suspicion of traversing outside a subway vehicle. Mere days following Ebba and Zema’s demise, the N.Y.P.D. unveiled a thirteen-second snippet, on Instagram, of an averted surfing endeavor: in the recording, a pair of individuals detach from the surface of a stationary train car, hurrying inward rapidly, as if startled. The constabulary furnished the material via drone; it is a segment of the “Drone as First Responder” initiative, instigated by the police commissioner, Jessica Tisch. (One of Tisch’s initial assignments for the municipality was inaugurating the N.Y.P.D.’s bureau of information technology.) The drones are intended to be a “force-multiplier,” in the public-safety deputy Kaz Daughtry’s description, supplementing the already-heightened police presence on the subways. They also render this presence more spectral, more all-encompassing.

Adams labels the arrests of surfers “saves” or “rescues.” He is correct that the arrests potentially conserve lives. Nonetheless, it is similarly factual that his government is encasing intrusive observation in the nonpolitical wrapping of safeguarding teenagers from their confused selves. The topic of security on the subway—a topic that unveils displeasing and deceitful schemes of supposed civic restoration, of the expansionism of Ed Koch and the animosities of Giuliani—had been framed by a pair of detonations of brutality in the aftermath of the pandemic: the Sunset Park gunfire, and the slaying of Jordan Neely. The aggression that the surfer commits, conversely, is to their own person. It is criminalized, generally as reckless endangerment, yet isn’t categorized in the minds of average citizens as a societal offense. The drones bestow Tisch’s broader surveillance operations—which encompass the corralling of over a thousand underage, primarily Black and Latino New Yorkers into factions within a “Criminal Group Database”—the veneer of the harmless. (She is additionally advocating for a repudiation of “Raise the Age,” the state regulation that detains youths below eighteen from adult courts.)

Demetrius Crichlow, the president of N.Y.C. Transit, is a transit worker of the third generation. The prior year, after almost three decades employed at the M.T.A., he obtained the role supervising the subways and buses, placing him second in command solely to Janno Lieber, the director of the M.T.A., who assumed the uppermost position after Andy Byford, the implored savior of our foundering subways, departed resentfully under previous Governor Andrew Cuomo. Crichlow sets Adams’s pathological confidence in opposition to a sense of paternal concern. Subsequent to the demises of Ebba and Zema, Crichlow cautioned, “Getting atop a subway isn’t ‘surfing’—it’s suicide.” And what else is it?

During my adolescent years, I allocated two to three hours daily on the subway. It was a liminal realm, plainly transitional, just shy of a place. I recall perceiving, within the subway, that we youths wielded an extortionate impact over grownups, who diminished out of irritation as we dispersed ourselves within the vehicles yet diminished, regardless. We were at liberty to misbehave in the subway due to it being an authority void between abode and academia. There existed an unspoken display in the manner we reclined as proximate to the platform’s margin as conceivable while awaiting the train, compelling ourselves not to wince when the express car careened into the station. What was favored back then wasn’t as much riding on the rooftop as riding in the gaps between vehicles. I couldn’t partake; a relative of mine had perished, one January morn, subsequent to being impacted by an E train in Queens. Nevertheless, with a fusion of envy and magnetism, I observed my acquaintances be jolted from flank to flank, feigning impassivity. And we were nobody. I was acquainted with youths who could journey miles through the subway passages, their acquaintance of the arrangement so absolute.

Eyewitnesses on the J recollect perceiving a cohort of youths alongside Ebba and Zema antecedent to their calamitous journey, purportedly rousing the females. For a handful of days after their deaths, their social-media profiles were still reachable. It was agonizing to behold the clips they had deserted, a type of existent pathway to their obliteration. A subjective recording showcases the void of a passage receding at high velocity, implying that the girl capturing must have been suspended off the facade of the concluding vehicle of a mobile train. A girl reclines on rails in another; someone must have been down there alongside her to secure the shot. A plethora of the innards of dilapidated and derelict edifices, a plethora of capturings of the nocturnal, documented atop scaled bridges, all filmed unsteadily. This constitutes a dual rush: the peril of the act itself, succeeded by the fulfillment of uploading verification. As of late, New York City appended a suit to the dozens that have already been filed by local governments against social-media enterprises such as Meta, which possesses Instagram, and Bytedance, the proprietor of TikTok. The municipality asserts that social media has unleashed a youth mental-wellbeing crisis, and that the indiscriminateness of algorithmic logic has propelled surfing recordings to the vanguard. (Social-media enterprises have, in years prior, cooperated with the municipality by flagging recordings.) In submitting the litigation, the municipality was emulating the example of Norma Nazario, who, in 2024, prosecuted TikTok and Meta for the unjustified demise of her fifteen-year-old offspring, Zackery, who succumbed to surfing, alleging that algorithms incentivized her offspring to become addicted to the action. Meta and TikTok have appealed to have the litigation discarded; the tribunals have dismissed these appeals.

Any individual possessing a fleeting comprehension of New York City subway lifestyle acknowledges that traversing outside the train precedes social media. It was historically an undertaking linked to outer-borough youths, Black youths, brown youths, their demises already foreordained. In 1996, when a fourteen-year-old voyaging atop a 2 train impacted a signal beacon and plunged onto the tracks to his undoing, Giuliani, in his broken-windows peak, offered the pronouncement that the boy’s progenitors bore some accountability for his expiration. Presently the callousness that delineates our sentiments toward children has a receptacle in social media. We censure the digital platforms, and scorn these youths as moronic daredevils, addicts—even as the most astute grownups amongst us manifest a parallel dependency on platforms to dictate who they should be.

The TikTok subjective voyages of youths on a moving train do gain traction for a period, even if they’re eventually eliminated. Nevertheless, the recordings insinuate more than sheer ostentation or thrill-seeking; they stand apart from other instances of internet exposure. The intensification in surfing appears to directly parallel the advent of a more scarred New York City subsequent to our severe isolation: there were nine hundred and twenty-eight accounts of individuals traversing external to train vehicles in 2022, contrasted with four hundred and ninety in 2019. This is amongst the plethora of crises that the Adams administration will deposit on its desk for Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani to address. Mamdani has suggested that he intends to retain Tisch, the reviver of anxieties concerning so-called youth misconduct, as his police superintendent. However, it stands to reason that, considering Mamdani’s strategies to offload particular community-safety matters from the constabulary, prevention will manifest contrarily within his government. Surfing is an atypical tragedy. We cannot apportion condemnation wholly to systemic imperfection. This quality of abnormality is what renders unintended surfing fatalities seem unavoidable—or, rather, inescapable, woven into the subway’s potency.

Contemporary surfing coincides with a surge in posting regarding urbex, abbreviated for urban exploration of derelict areas, which, in New York City, exposes the city’s perpetual fissure: accelerated commercializing, rampant abandonment. There is an authentic fervor to plunge oneself into the neglected extremities of the city. Y’Vonda Maxwell, the parent of Ka’Von Wooden, who perished plunging from a J train in 2023, recounted to the Times that trains were all “he ate, contemplated, verbalized about.” In 2022, Kosse Laureano plunged to his fatality off a 7 train at Hudson Yards. His friend Alexander Antelman fashioned a recording he entitled “Underworld: A Memorial to Kosse Laureano (2004-2022),” a compilation of Laureano’s exquisite and chilling snapshots of trains in ordinarily concealed motion. This isn’t merely a fixation with peril but with the subway in itself—its disused track constructions, its disused inclines, its disused husks. Surfers are engrossed in desertion. Or, as one informed Curbed the prior year, “It’s a form of expression. It’s a form of art.” His certitude is enraging, albeit not beyond apprehension—it’s the certitude of a child who aspires to commandeer the metropolis prior to being devoured by it. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com