The photographer Al Thompson arrived in the United States as a teen-ager from Jamaica, in 1996, to join his mother in Spring Valley, a New York City suburb situated in Rockland County. “What was surprising to me was how big everything was,” Thompson told me recently, about visiting shops and stores during his first days in his new home. Buying CDs, making cassettes, being grounded for the first time, and playing soccer and basketball in Spring Valley Memorial Park—a focal point of the community, where he encountered a medley of “languages, accents, and inflections”—were the activities that initiated him into American teen-age life. At the time, Rockland County was one of the most diverse places in the country, and host to the largest Haitian population outside of the Miami area—Haitian Presidents have made it a point to visit this “Little Haiti” during diplomatic missions in the U.S.

In recent decades, Spring Valley’s residents of color have struggled. The nationwide drug and crime epidemics of the eighties devastated large segments of the community, affecting the area’s youth in particular. Since then, parts of the city have gentrified, while others have fallen into blight. Slowly, the black and Hispanic populations have decreased, as new, wealthier residents have moved in. A growing presence of Haredi, or ultra-Orthodox, Jews has led to tensions reminiscent of those between Jews and blacks in Crown Heights in the late eighties. Now, in his ongoing photo series “Remnants of an Exodus,” Thompson attempts to capture the residue of these home-town upheavals.

Thompson hasn’t lived in Spring Valley for ten years, since he left for college. During that time, his mother has been slowly driven to the outskirts of the city, as the prices of homes in the center have skyrocketed. “I had been hearing about changes in the community for a while,” Thompson said. “And one day, about three years ago, I drove through to take a look for myself.” He went around his old neighborhood, looking for traces of his favorite places—restaurants and music stores—and found that they had been replaced by more popular franchises. The Seventh-day Adventist church, a few blocks away, had a smaller congregation than it used to. He searched, to no avail, for old spots where he would go to listen to people freestyle rap. “But I kept coming back to the park,” he said.

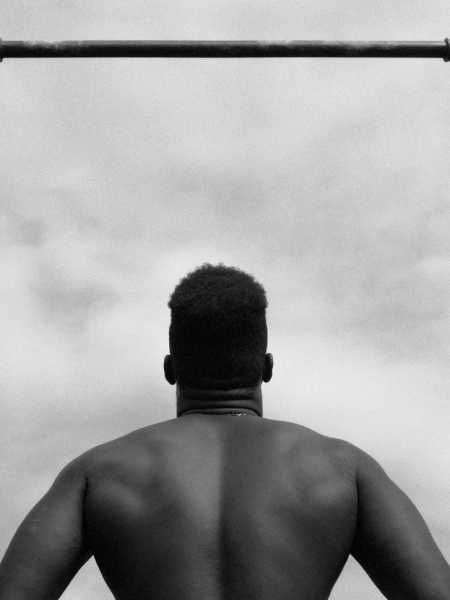

In his memory, Spring Valley Memorial Park was vibrant and diverse, crowded with “super-duper-sweaty bodies under floodlights” and filled with “the sound of sneakers shrieking on the concrete.” Now, he says, fewer people play there, and its central role in the community has diminished. The park’s parallel bars, mesh fencing, cracked concrete, and debris-filled streams became the focus of “Remnants of an Exodus,” symbols of the old neighborhood he knew.

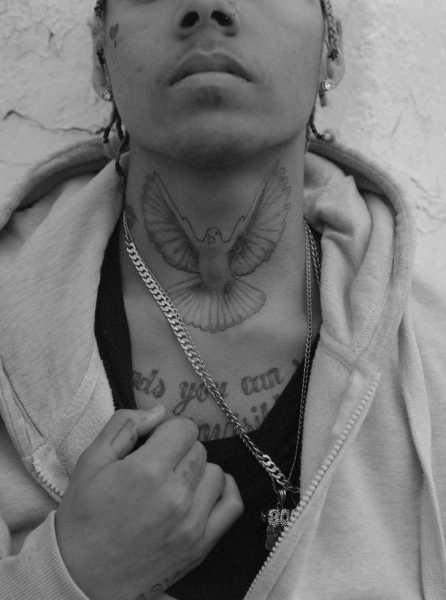

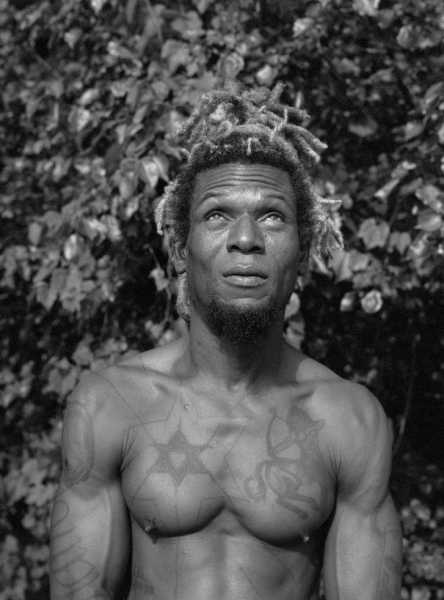

Thompson said that many of the people he spoke to in Spring Valley expressed a sense of “dejection.” Many still feel connected to the community, as he does, but can no longer afford to be a part of it, and so come from far away to play soccer in the evenings, if they can find old friends. Thompson’s sparse, black-and-white palette conveys a tenderness and affection for his subjects. One photo captures Emmanuel, a man whom Thompson describes as the local historian, knowledgeable about everyone and everything. The framing of his multicolored, dreadlocked hair and solid, tattooed form calls to mind Renaissance portraits of the ideal man in his ideal place.

It is the destiny of every place, in the long run, to see new people arrive and old ones go. One of gentrification’s peculiar wounds is its threat to the architecture of memories, as new stories, new histories, get imposed upon old ones. Through his photographs, Thompson attempts to reëstablish his sense of belonging in Spring Valley. Mourning what is lost, he achieves the harder feat of celebrating what will, within the people who lived and still live there, remain.

Sourse: newyorker.com