Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

If you haven’t been closely following fashion periodicals like W, i-D, Luncheon, and Vogue across its global editions in the last several decades, chances are you’re unfamiliar with Paolo Roversi’s artistry. However, within those publications, he has been a uniquely refined and remarkable figure; amidst a period where numerous celebrated contemporaries in fashion photography are either deceased or discredited, Roversi, at seventy-eight, persists as a vibrant virtuoso of the craft. His body of work has garnered heightened recognition of late, showcased by a presentation last spring at the Palais Galliera, situated in Paris, and another recent exhibition at the Pace gallery, located in New York. A catalogue accompanying the Paris display, simply entitled “Paolo Roversi,” offers an excellent introduction to the artist, though his preëminent pieces possess such vigor that they transcend the confines of print or display.

.jpg) Kate, New York, 1993.Photography courtesy Pace Gallery

Kate, New York, 1993.Photography courtesy Pace Gallery Audrey Tchekova, dress by Atsuro Tayama, Spring-Summer 1999, Paris, 1998 (Max Mixt(e), Spring 1999).

Audrey Tchekova, dress by Atsuro Tayama, Spring-Summer 1999, Paris, 1998 (Max Mixt(e), Spring 1999).

Roversi, who is predominantly self-taught and of Italian origin but operating out of Paris, has been diligently producing work since the beginning of the nineteen-eighties. His longevity stems from a consistent emphasis on artistry within commercial contexts. Similarly to Irving Penn during his later career, Roversi draws particular inspiration from groundbreaking designers, notably John Galliano, Romeo Gigli, Yohji Yamamoto, and Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garcons. His portrayals of their innovative attire are imbued with a painterly and romantic essence—resembling expressionistic renderings rather than meticulous documentation of the garments. Displayed in tandem with his fashion contributions are portraits and nudes, frequently showcasing the same models already captured in full attire. These images are candid, typically frontal, and remarkably gentle, echoing Julia Margaret Cameron’s delicate, sepia-hued portrayals of acquaintances and kin from the Victorian epoch. Roversi’s oeuvre possesses a level of intimacy and perceptiveness that never veers into exploitation. The physique invariably functions as an extension of the portrayal, rather than a detached sculptural form.

Sasha Robertson for Yohji Yamamoto, Autumn-Winter 1985-1986, Paris, 1985.

Sasha Robertson for Yohji Yamamoto, Autumn-Winter 1985-1986, Paris, 1985. Tami Williams, dress by Christian Dior, Autumn-Winter 1949-1950, Paris, 2016.

Tami Williams, dress by Christian Dior, Autumn-Winter 1949-1950, Paris, 2016. Molly Bair, Chanel dress from the Spring-Summer 2015 haute-couture collection, Paris, 2015 (Vogue Italia, March 2015).

Molly Bair, Chanel dress from the Spring-Summer 2015 haute-couture collection, Paris, 2015 (Vogue Italia, March 2015). Kirsten Owen for Romeo Gigli, Summer 1988, London, 1987. Original Polaroid.

Kirsten Owen for Romeo Gigli, Summer 1988, London, 1987. Original Polaroid.

Roversi readily acknowledges Man Ray and Erwin Blumenfeld as significant forebears, both of whom were active within the domain of mid-century fashion publications and distinguished themselves through their manipulation of imagery within the darkroom. Their methods—encompassing adjustments to tonality and hues, as well as the superimposition, extension, or solarization of images—bestowed their photographs with a striking, frequently startling intensity. Roversi operates almost exclusively using Polaroid film, in both chromatic and achromatic formats, and his particular intensity tends to manifest more subtly, characterized by the soft radiance evocative of an Impressionist canvas. The Polaroid medium fosters a spirit of experimentation concerning both the tangible components and the resultant visual. Mirroring the approach found in William Klein’s photographs, Roversi’s works incorporate chance occurrences, light bursts, blurring, and even imperfections. Irrespective of how two-dimensional the outcomes might appear when reproduced, they possess a substance that defies encapsulation within a singular plane. Roversi’s most accomplished fashion images convey a feeling of incompletion, of animation—as though they are still coalescing before the observer’s gaze.

Luca Biggs for Alexander McQueen, Autumn-Winter 2021-2022, Paris, 2021.

Luca Biggs for Alexander McQueen, Autumn-Winter 2021-2022, Paris, 2021.

Roversi anchors his perpetually evolving methodologies in photographic convention by primarily utilizing a studio situated in Paris, which has served as his workspace for the majority of his professional life. For a fashion pictorial captured in a Parisian park in 1995, he transported a textile backdrop, fashioning an open-air enclosure reminiscent of the mobile studios that Penn conceived for his “Worlds in a Small Room” sequence of ethnographic likenesses from Dahomey, Nepal, Morocco, and other remote destinations. Like Penn, however, Roversi generally favors working within a more comfortable and established setting. Within the exhibition catalogue, which comprises a succession of dialogues with the Paris exhibition’s curator, Sylvie Lécallier, Roversi states, “I need to be kind of shut away in a room. I need to be hemmed in.” A number of the book’s most compelling photographs depict the studio itself, appearing bare save for a pair of stilettos reflected across a wall of looking glasses or a disarranged military-issue blanket, a favored background, fastened to an unadorned partition.

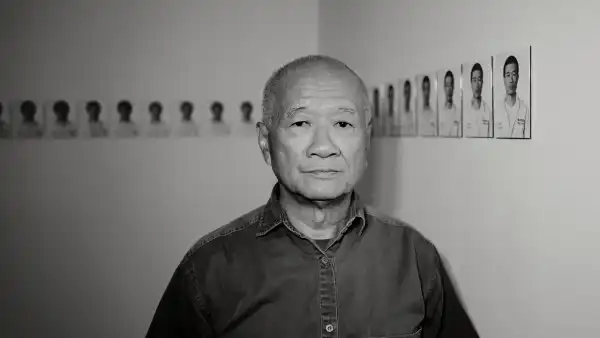

Jerome Clark, Paris, 2005 (Uomo Vogue, February 2006).

Jerome Clark, Paris, 2005 (Uomo Vogue, February 2006). Light, Paris, 2002.

Light, Paris, 2002.

For Roversi, the studio represents “like an empty stage, a space waiting to be filled, a time yet to be invented, where neither seasons, nor days, nor hours exist.” He is discernibly engrossed in the allure of photography, from the astonishment and revelation of its initial epochs to the most demanding endeavors of his fellow artists, and his body of work conveys a profound consciousness of both the present juncture and the days, years, and decades that preceded it. He expands the capabilities of the Polaroid technique to manifest the visuals that remain solely within his imagination until they surge into existence within his processing chamber. “Every step forward, every evolution of my work, was the result of an accident,” Roversi communicated to Lécall

Sourse: newyorker.com