On March 18, an email went out from the World Health Organization soliciting donations for its Covid-19 Solidarity Response Fund, to support WHO’s work tracking and treating the novel coronavirus. The sender address was “[email protected],” and who.int is the real domain name of the organization.

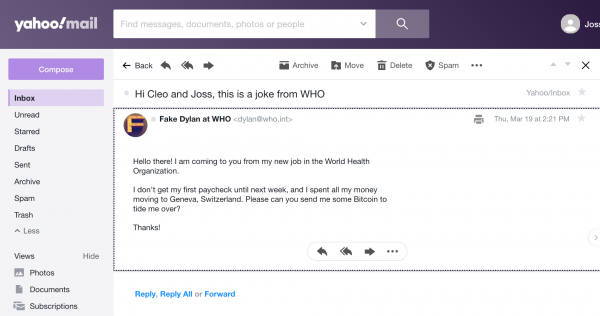

But the email is a scam. It was not sent from the WHO, but from an impersonator looking to profit off our tendency toward generosity during a global crisis. Fortunately, the attacker revealed themselves by asking for donations in bitcoin.

This is just one of many fake emails that have spoofed the WHO’s domain name during the coronavirus pandemic. Some are addressed from Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the director-general of the WHO, and carry attachments that can install malware on the victim’s device. Others announce a coronavirus cure that you can read all about in the attachment. They each appear to be sent from a who.int email address.

If it seems like it shouldn’t be this easy to impersonate a leading global health institution, you’re right. As we outline in the video at the top of this post, there is a way for organizations and companies to prevent spoofing of their domain, but the WHO hasn’t done it.

“One of the things that a lot of NGOs and nonprofits don’t necessarily understand is that email is a very open protocol by design,” said Ryan Kalember, who leads cybersecurity strategy at Proofpoint.

That “open protocol” means that the email transmission system itself doesn’t verify the identity of senders. Instead, senders and receivers have had to organize voluntary authentication methods: Domain owners can adopt an ID system, and email providers can check for for those IDs. But participation has not been universal on both sides.

“There are just so many organizations that don’t authenticate their mail. So if you are interested in tricking someone, that becomes an incredibly useful vector to do so,” said Kalember.

There are three main pieces of jargon to learn when it comes to email authentication systems. There’s SPF (Sender Policy Framework), through which a domain owner can specify that legitimate emails always come from a certain set of IP addresses. There’s DKIM (Domain Keys Identified Mail), which relies on a unique signature to verify senders.

And then there’s DMARC, which builds on SPF and DKIM by specifying how the receiving email service should treat messages that fail those tests (do nothing, send to spam, or reject the message altogether). It also provides a feedback system so that domain-owners can learn about messages passing or failing checks from their domain.

Setting a strong DMARC policy is the surest way to prevent domain spoofing, and all major email providers like Gmail, Outlook, and Yahoo, will check incoming emails against a DMARC record.

The WHO has enabled SPF but there is no DMARC record for who.int as of April 1, 2020. “The SPF record is a good thing to have, but without a corresponding DMARC policy, it won’t unfortunately result in spoofed messages being blocked,” Kalember said.

Sure enough, we ran some experiments with help from Dylan Tweney at Valimail, an email cybersecurity company, and easily placed a spoofed who.int email into our Yahoo inbox. Outlook and Gmail caught it in their spam filters, the last line of defense. We also tried spoofing voxmedia.com and cdc.gov, and neither reached an inbox. Both have strong DMARC policies in place.

A study conducted in 2018 by researchers at Virginia Tech similarly found that their experimental phishing email “penetrated email providers that perform full authentications when spoofing sender domains that do not have a strict reject DMARC policy.”

Unfortunately, it’s extremely common for domains to lack a strict reject DMARC policy. WHO is joined by whitehouse.gov, defense.gov, redcross.org, unicef.org, and the health agencies of Washington, California, Italy, South Korea, and Spain, among many others.

According to a recent report by Valimail, more and more domains are setting DMARC records, but less than 15 percent of those with a DMARC record actually have a “reject” policy to prevent spoofed emails from being delivered.

“The current situation is that not everybody is doing it. So essentially the problem is that you cannot punish other people for not doing it. You cannot just block their emails automatically because you will not receive legitimate emails from them,” said Gang Wang, professor of computer science at University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign.

Wang and his colleagues interviewed email administrators in 2018 to investigate the low adoption rates of the authentication systems and found that “email administrators believe the current protocol adoption lacks the crucial mass due to the protocol defects, weak incentives, and practical deployment challenges.”

The authentication systems can be difficult to configure for organizations that allow many third-party vendors to send emails, or that use forwarding and email lists. If DMARC is not set up carefully, legitimate emails might not get through, which may weigh heavily in the cost-benefit calculation for organizations. According to one of Wang’s survey respondents:

The benefit of protecting unknown victims from potential fake emails marked with your domain name may be less obvious than the costs, in everyday contexts. But right now, as cyber criminals deploy coronavirus lures en masse and we’re all desperate for information from authorities, the benefits seem much more clear.

The WHO did not respond to our request for comment.

You can find this video and all of Vox’s videos on YouTube. And join the Open Sourced Reporting Network to help us report on the real consequences of data, privacy, algorithms, and AI.

Open Sourced is made possible by the Omidyar Network. All Open Sourced content is editorially independent and produced by our journalists.

Sourse: vox.com