This story is part of a group of stories called

Finding the best ways to do good. Made possible by The Rockefeller Foundation.

If any one image helped illustrate the unique nature of the humanitarian crisis in Venezuela, it was a photograph taken in February, showing two shipping containers and a fuel tanker blocking a bridge to Colombia. The purpose of the barricade was to keep out a convoy of US-donated aid making its way to Venezuela from Bogota.

The attempted aid initiative took place in a particularly tense political context. Weeks earlier, the US had officially recognized opposition leader Juan Guaidó as Venezuela’s interim president, but the government of Nicolás Maduro — which brought about the country’s economic collapse through mismanagement and corruption — clung to power.

For the Maduro regime, squashing what it saw as a politically motivated relief effort was a way to keep US and opposition influence at bay. It was also a move that tracked with Maduro’s long history of turning down humanitarian help — he often notes his is not a nation of beggars and blames economic woes on US sanctions — even as there were signs of increasingly alarming conditions inside Venezuela. As Vox’s Alex Ward reported earlier this year:

The once-rich oil country is facing malnutrition; four out of five households live in food insecurity; and more than one in 10 Venezuelans are undernourished. And it’s grappling with the comeback of nearly eradicated tropical diseases, as well as a reduced life expectancy.

The immensity of the need in Venezuela meant that the government, in an about-face, has started allowing some streams of aid in recent months, including shipments of medical supplies and power generators from the Red Cross.

But Maduro’s refusal to formally declare a humanitarian emergency makes it impossible for many other international agencies, including UNICEF and the World Food Programme, to get involved. And the humanitarian supplies that do make it to Venezuela can’t be easily distributed where they need to get to, since basic transportation infrastructure in the country has crumbled, and soldiers often steal provisions at military checkpoints. Meanwhile, the small local aid groups that do their best to feed the hungry in the absence of significant foreign assistance are accused by officials of anti-government activism.

In that intractable landscape, Venezuelans in need have increasingly turned to a new tool to receive aid, one that facilitates the delivery of both charitable donations and remittances: cryptocurrency. As Venezuela continues sinking into the worst economic crisis in its history, it is also emerging as a unique case study for the potential of digital money to make aid possible and decrease suffering in distressed countries.

Cryptocurrency-powered aid is making a difference in Venezuela

Imagine you’re a Venezuelan living in the US. You have family members back home in Caracas, the capital, who you know are hanging in there, but desperately need some help.

But there are very few avenues at your disposal. You could try shipping packages filled with necessities, like shampoo or clothes or canned food, but there’s no guarantee that those would make it to their intended recipients. You could wire your relatives, or local nonprofits, some money, but bank transfers can take a long time, and the Venezuelan government would slap heavy fines. So, you grab your smartphone and turn to a last resort: bitcoin. That allows you to tap into a new and growing ecosystem of aid delivery in Venezuela, one that’s built entirely around direct, intermediary-free cryptocurrency transactions.

Take local charities like the Bitcoin for Venezuela Initiative or EatBCH. They receive cryptocurrency donations from around the world — incurring almost no cost or fees from intermediaries along the way — to purchase food for the needy in Venezuela. Reaching people at soup kitchens and distribution centers across the country, those two operations serve thousands of meals a day. It’s a model that is now being replicated in places like Nicaragua or South Sudan.

There’s also been experimentation with direct cryptocurrency transfers. Earlier this year, GiveCrypto, a San Francisco charity, provided temporary assistance to hundreds of vulnerable families in Venezuela through weekly crypto deposits worth around $7. Every week from February to April, families received the deposits through a smartphone app, which they were then able to trade for local currency through online transfers. As CNBC reported, that weekly infusion of digital money — equal to the monthly minimum wage in Venezuela — helped participating families stop having to skip meals.

Another initiative, spearheaded by online currency exchange platform AirTM, will “airdrop” a one-time crypto payment of $10 to 100,000 individuals in Venezuela this coming August. So far, the company has raised about $300,000 from donations toward its $1 million goal.

Cryptocurrency has also paved the way for fast, cost-effective remittances — money transfers from friends and family abroad — that elude government restrictions.

As Moises Rendon, an associate director at the Center for Strategic & International Studies, told me, remittance flows have become the second-largest source of income in Venezuela, after oil production, with about $300 million dollars coming in to the country every month from abroad. That’s made the government eager to take a cut. As Alex Gladstein writes in Time:

Cryptocurrency-based remittances, though, can circumvent those controls. Sending bitcoin to family members back home in Venezuela, for instance, takes moments and only incurs a small fee. Since that asset is sent directly to the recipient’s phone — as opposed to being routed through a bank or another financial institution — it is safe from government interference and can be easily liquidated through local exchanges.

Looking forward, innovation in the crypto space in Venezuela will likely only accelerate as hyperinflation remains on track to surpass 10 million percent by the end of the year, according to the IMF. After all, the dramatic collapse of the bolivar means that the logistics of making conventional payments are becoming more and more difficult; cash is scarce and traditional payment networks are overloaded. And it means that saving money is nearly impossible, because its value drops so quickly if left unused. Their own volatility notwithstanding, cryptocurrencies could help on both those fronts, especially as a growing number of merchants in the country start accepting a number of different digital currencies as payment.

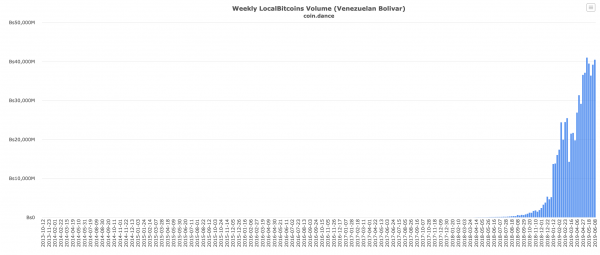

As a result of all this, Venezuela already finds itself ranked as the fourth country in the world in bitcoin trade, with the average daily volume of the cryptocurrency traded on LocalBitcoins — just one of several online marketplaces where people can exchange bitcoin for local currency — reaching 5.2 billion bolivares.

As Joe Waltman, the executive director of GiveCrypto, told CNBC: “Crypto has the highest likelihood of being helpful to people in places where money is broken … and there’s probably no better example of broken money right now than Venezuela.”

Cryptocurrency and the future of humanitarian aid

When it comes to the potential of blockchain and digital currencies to help revolutionize humanitarian aid systems, excitement abounds.

With international relief organizations losing up to 3.5 percent of every aid transaction to different costs and fees — and with 30 percent of all development funds being lost to corruption, according to former UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon — advocates say that intermediary-free cryptocurrency transactions are a less expensive way of doing business.

In addition, as direct cash interventions continue to gain traction in development circles, the kind of direct, peer-to-peer giving that blockchain technology makes so easy — and which is evident in Venezuela — can also come off as especially effective.

With nonprofits leveraging digital currency platforms to help vulnerable people in other countries as well, a growing number of donors are sitting up and taking notice.

But just as Venezuela is shining a spotlight on the humanitarian potential of cryptocurrency, it is also underlining how far away that technology still is from being able to truly revolutionize current aid systems. For one, cryptocurrency transactions depend on a functioning electricity grid and stable internet service, both of which have been far from guaranteed in blackout-ravaged Venezuela.

More operational challenges in that country — which are also present in many others in the developing world — include limited smartphone penetration and less-than-widespread computer and financial literacy. That means the humanitarian benefits of crypto are difficult to scale up.

“Basic services are not working. Many cities don’t have electricity for 10 to 12 hours every day,” Rendon says. “So yes, crypto has potential to help but the situation is so extreme that it’s hard to see the crypto benefits scaling to the level that is needed.”

Another stumbling block is that, when it comes to crypto-giving, concerns around accountability and transparency have yet to be resolved, in part because the parties involved in a transaction can largely remain anonymous.

“Anyone who tells you that they can track inside Venezuela with 100 percent accuracy and prove that a donation has been spent in two bags of food, that’s not true,” said Randy Brito, the founder of the Bitcoin for Venezuela Initiative, which uses cryptocurrency donations to buy and distribute food inside the country.

EatBCH runs a very similar operation to the Bitcoin for Venezuela Initiative. Their accountability system is to upload photos on Twitter that show folks eating donated food and a handwritten sign with the code of the transaction that helped pay for it. As Rendon notes, “That’s good enough for a few thousand dollars [in donations]. But not for like half a million dollars.”

Another obstacle that might stand in the way of cryptocurrencies’ adoption among the donor community is their somewhat dubious reputation and connection to illicit activities like money laundering. That narrative is one that recent developments in Venezuela helped perpetuate: Last year, the government tried (and failed) to launch a state-sanctioned digital currency — the petro — in large part to circumvent international sanctions.

So cryptocurrency will not be the silver bullet that resolves the humanitarian crisis in Venezuela. The dimension of the hardship faced by the population is too big, and the streams of aid crypto makes possible are too new, and too difficult to expand.

That said, crypto’s ability to help put food on the table for some people — and the bigger-picture role it plays helping reestablish free market mechanisms in a damagingly repressive economic context — shows the technology’s philanthropic potential. As Rendon summed up: “It’s taking control away from the regime and empowering the people.”

If Venezuela teaches us anything, it’s that, for those living under authoritarianism or suffering from hyperinflation, bitcoin, Ethereum, and other cryptocurrencies can be useful financial tools. That’s something that the development community should keep in mind, especially when seeking to distribute aid to crisis areas in a more efficient, faster way.

Sign up for the Future Perfect newsletter. Twice a week, you’ll get a roundup of ideas and solutions for tackling our biggest challenges: improving public health, decreasing human and animal suffering, easing catastrophic risks, and — to put it simply — getting better at doing good.

Sourse: vox.com