This story is part of a group of stories called

Evidence-based explanations of the coronavirus crisis, from how it started to how it might end to how to protect yourself and others.

Five months ago, the US was outpacing almost every country, except Israel, in vaccinating its people against Covid-19. Nearly 1 in 5 Americans were already fully vaccinated; Hungary stood out as a success among European countries, but still only 1 in 10 people had received a full regiment of the vaccine by April 6. Most of Europe lagged in the single digits.

The speed of the rollout, combined with the United States’ role in developing and producing the vaccines, seemed to make vaccination a latter-day example of American exceptionalism, one that delivered a decisive blow against the virus that had upended life around the world for the past year.

But over the summer, America’s Covid-19 vaccine success story morphed into a tale of mediocrity and missed opportunities — while countries in Western Europe and Scandinavia caught up with, then surpassed, the United States in their vaccination campaigns.

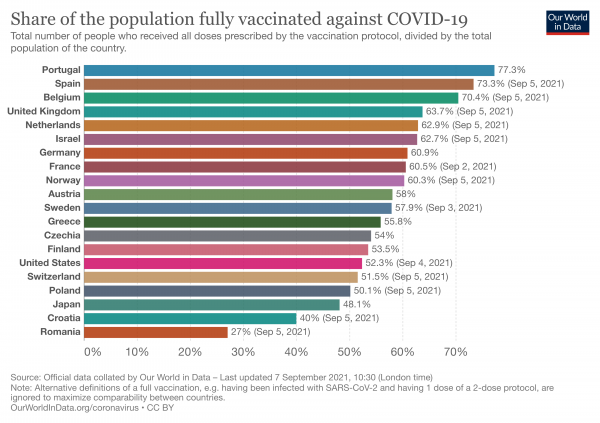

Portugal is currently setting the pace in Europe, with nearly 80 percent of its people fully vaccinated. Spain and Belgium have reached over 70 percent of their populations. France, Germany, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Norway are all above 60 percent.

Meanwhile, America now looks thoroughly mediocre among wealthy nations, with 52.3 percent of its total population vaccinated as of September 7. The US now ranks 57th in the world in the percentage of its population vaccinated, according to Bloomberg’s vaccine tracker.

Only a handful of Western European countries — Switzerland, in particular, stands out — currently rank behind the US in their vaccine drives. In poorer parts of the world, meanwhile, many people are still waiting to be vaccinated because of a lack of supply.

President Joe Biden is currently trying to push more Americans to get vaccinated, as the delta variant drives deaths to levels not seen since early February. The administration is reportedly announcing Thursday that the vast majority of federal workers and contractors will be required to receive the vaccine. Biden is also urging private companies and schools to impose their own vaccine requirements.

“We had the lead and then fell behind,” Céline Gounder, an infectious disease epidemiologist, said. “We were quick to vaccinate the half of the population that was eager to be vaccinated but then hit a plateau.”

Israel, once held up as model of efficient vaccinations, has also stagnated: Its vaccine coverage increased only marginally in the past few months, from 56 percent in April to 63 percent in early September.

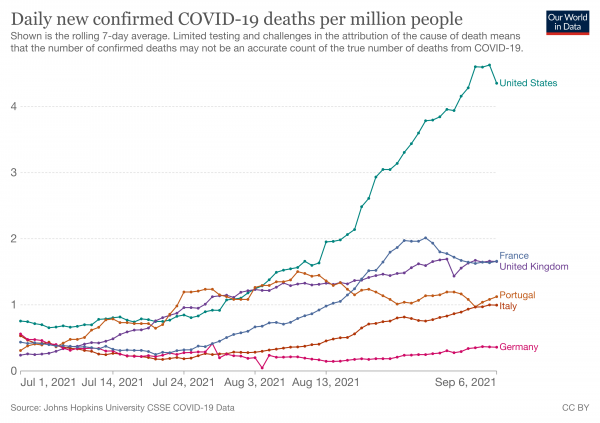

The US is paying a heavy price for the failure to maintain its strong start to vaccinating people against Covid-19. Cases have grown dramatically over the past two months, making this the second-worst wave of the pandemic. The average number of daily deaths in the US has increased from fewer than 200 in early July to about 1,500 now. Adjusting for population size, America is experiencing more than twice as many Covid-19 deaths every day as countries like France, Germany, and Italy that have been more successful at vaccinating people against the virus.

Why America’s Covid-19 vaccination campaign fell behind much of Europe

The United States started its vaccination drive with a structural advantage. It had the most generous supply of Covid vaccines, along with Israel, thanks to investments made to procure doses before the vaccines were approved for emergency use by the US Food and Drug Administration.

Europe, meanwhile, struggled to acquire and distribute vaccine doses out of the gate, as Politico Europe covered in a January investigation. That enabled the US and Israel to get off to their hot starts while the EU had to catch up as vaccine supply improved over the spring and summer. (That also meant the latter had more room to grow than the United States, which had already gotten shots in the arms of its most willing citizens.)

Demographics may also be holding the US back to a degree. America has more young people than most Western European countries: About 16 percent of Germany’s population is under 18 versus about 22 percent of the US’s, to give one example. Children under 12 are still not eligible for vaccines in the US (or anywhere else), which may be partly depressing its vaccination share.

But there is more to the story than supply quirks or demographic trends.

Compared to a country like Portugal, now a world leader in Covid vaccinations, the United States’ vaccination rates for its eligible population are not particularly strong either. In Portugal, 99 percent of people over age 65 are fully vaccinated; in the US, the share is closer to 80 percent. Those disparities persist in the younger age cohorts: 85 percent of Portuguese people ages 25 to 49 are fully vaccinated versus less than 70 percent of the Americans in the same age range.

Another big difference that explains that divergence is one of culture and politics. Covid vaccinations have become, like so much of America’s pandemic response, polarized along political lines. As of July, 86 percent of Democrats said they were vaccinated, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation survey while only 54 percent of Republicans said the same. One in 5 Republicans said they would “definitely not” get the vaccine.

“This political divide over vaccines has contributed to the US falling behind European countries when it comes to coverage levels,” Josh Michaud, associate director of global health policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation, told me.

There are pockets of vaccine hesitancy in Europe, especially in Germany and France, but nothing on the scale of what we have seen in the United States. In Portugal, as reflected in its exemplary vaccination rate, skeptics have a very low public profile.

“We don’t need to convince people to get vaccinated,” Gonçalo Figueiredo Augusto, who studies public health at NOVA University Lisbon, told me over Zoom. “People want to.”

How Portugal became a world leader in vaccinations

A difficult history may have, oddly enough, set Portugal up for success, Augusto said. The country lived under a dictatorship from 1933 to 1974, and public health efforts stagnated in that time. Driven by preventable deaths from infectious diseases, the child mortality rate in Portugal remained substantially higher than it was in wealthier European countries like France, Germany, and the UK. It was only in the final years of the regime in the early 1970s that an earnest vaccination campaign began.

“People were very willing to get the vaccines because infectious diseases were a huge problem,” Augusto told me. “We were a poor country then and we learned how important vaccines were.”

As Portugal’s democracy was reestablished and economic conditions improved, so did public health. Child mortality had fallen in line with those other countries by the 1990s.

But some of its citizens still carry memories of an era when routine vaccinations were not a given. More than 97 percent of Portuguese children are vaccinated against the measles these days, Augusto said. But in the US, the share is lower, closer to 90 percent, as a small but sizable portion of the population continues to resist that inoculation.

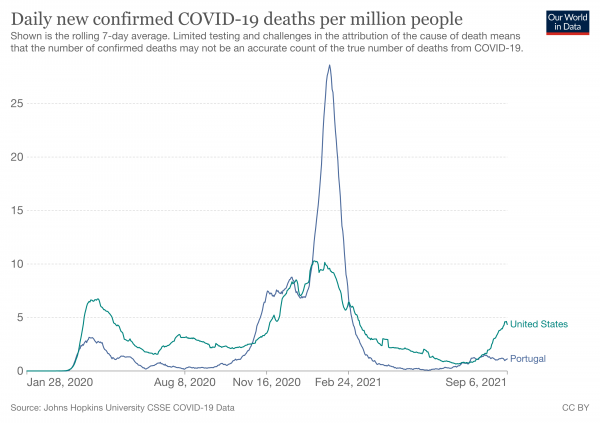

Portugal is also carrying the more recent memories of a devastating winter wave from Covid-19, like many countries, including the US. After largely dodging the worst surges of last spring and summer, social distancing restrictions were relaxed. The country’s leaders wanted to allow the Christmas holiday to unfold as normally as possible in 2020.

By early January, case numbers were rising rapidly and deaths soon followed. For a time, Portugal had the worst Covid death rate in the world. “The idea that the virus was very close was really felt in January,” Augusto said. “It was traumatizing for the country.”

In Portugal, vaccinations became regarded as the best way out of the crisis. Initially, the country was hobbled by the same supply shortfalls seen across Europe. But as more and more doses became available, vaccination rates picked up. As the elderly, people with compromised immune systems, and essential workers were vaccinated, death rates started to fall. That built more trust in the vaccines.

The US had its own deadly winter surge, and the recent delta wave seems to be coinciding with an uptick in vaccinations. But the share of Americans who are vaccinated still trails the Portuguese, even looking at only the eligible populations.

Portugal also adapted on the fly to a changing pandemic. When the delta variant arrived there in May, the national government decided to accelerate the dosing schedule for the vaccines. The interval between the first and second doses of the AstraZeneca, Pfizer, and Moderna vaccines was shortened by a week or more.

“The idea was to as quickly as possible vaccinate the population with two doses,” Augusto said. The country was aided by a highly centralized approach, with the national government taking responsibility for acquiring, distributing, and administering the vaccines. The military played a hands-on logistical role, too.

The aggressive rollout paid off. Portugal did see a small delta-driven wave of Covid cases and deaths in July and August, but it was much less severe than what the US is now enduring.

The country has also explicitly linked its vaccination rates to its reopening plans. Bars and nightclubs there have been closed for months, and the government has said they would be allowed to reopen once 85 percent of the population was vaccinated. It’s expected to reach that benchmark in a matter of weeks.

“You don’t want rules? Get the vaccine, help the country” is how Augusto described the message from government leaders to the Portuguese people.

Some US politicians and businesses are getting more comfortable with the same kind of idea, either mandating vaccinations outright or requiring them for certain activities. The Biden administration is now aggressively pushing vaccine requirements, with more to be announced by the president himself in a speech on Thursday. Democratic-led states and cities are taking similar steps. More private businesses are embracing vaccine requirements as well.

“In the US, we have come close to vaccinating everyone voluntarily willing to be vaccinated,” Michaud said. “So any further progress in getting lots of adults vaccinated is going to probably rely on vaccine requirements and mandates.”

But those efforts are meeting resistance from Republican politicians and voters, who portray them as un-American.

It is a microcosm of why the United States has fallen behind in its bid to vaccinate people against Covid-19 and get the pandemic under control. The toll of that failure keeps growing.

Will you support Vox’s explanatory journalism?

Millions turn to Vox to understand what’s happening in the news. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower through understanding. Financial contributions from our readers are a critical part of supporting our resource-intensive work and help us keep our journalism free for all. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today from as little as $3.

Sourse: vox.com