“Your baby is going to die. You’re putting your baby at risk.”

This is what Jill Arnold remembers her doctor telling her over and over, while she was in labor in August 2005.

Around 7 pm, Arnold started having regular contractions and was admitted to Kaiser Permanente in San Diego. A few weeks earlier, her doctor had recommended a planned cesarean section, which Arnold declined because she wasn’t convinced by her doctors’ reasoning. “I kept asking questions,” Arnold says, “and didn’t really think what they had to say” merited a C-section.

But a doctor insisted and, at one point during the labor, even asked Arnold’s husband to sign forms saying he consented to the risk of losing his child if his wife refused a C-section.

Help our reporting on pregnancy

Are you pregnant? Have you ever been pregnant? Or do you work with pregnant women? We’re reporting on pregnancy for a series here at Vox and we’d love to hear from you. Please check out this survey for Vox.

She did refuse, and less than five hours into her (unremarkable, uncomplicated) labor, with her husband and doula at her side, she delivered her healthy baby girl. The only scar that lingered from that day is the “unnecessary stress” of repeatedly being told her daughter could die.

We’ve long known that many C-sections — like the one Arnold’s doctor tried to pressure her into getting — are unnecessary, and that the unnecessary ones have become a problem in the US. The C-section rate in the US shot up by 60 percent between 1996 to 2011. Though it’s declined slightly in recent years, a third of all births in the country still involve the operation.

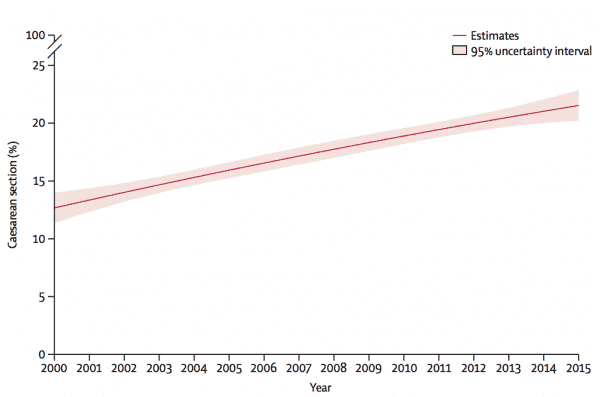

A new series on the procedure, published in the Lancet, suggests the US is by no means an outlier: The global C-section rate has doubled in less than a generation, from 12 percent of all births in 2000 to 21 percent in 2015.

While women in some areas still die during childbirth from conditions that could be addressed with C-sections they couldn’t access, “overuse and its implications are now of growing concern,” a Lancet editorial says.

In Latin America, C-section rates are 44 percent, compared with only 4.1 percent in Western and Central Africa. Optimal rates are generally considered to be between 10 and 15 percent of births, and the World Health Organization just put out new guidance on how to bring the global C-section rate down.

“There’s certain cases where everybody would agree a cesarean is appropriate,” says Gene Declercq, a professor of community health sciences at Boston University. “And there are cases where only a few fanatics would say a C-section should be done. But there’s this large number of cases in a gray area.”

Understanding that gray area is crucial to understanding how cesarean sections became a global epidemic, and what patients and health care providers — who usually make the decisions about when to do a C-section — should be doing about their overuse.

C-sections, explained

Over the last century, medical advances have transformed childbirth from the most common cause of death for young women and infants into a much more survivable one. And the C-section has been an important tool in an ob-gyn’s arsenal.

“It’s the most common major surgery that’s performed in humans,” Neel Shah, an assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School who was not involved with the Lancet series, tells Vox.

No one is more eloquent on what a C-section involves than surgeon and New Yorker staff writer Atul Gawande, who described the procedure in extraordinarily vivid detail in a 2006 article about childbirth:

Another uterine contraction, and doctors deliver the placenta through the cut. The mom is sewn up, and the procedure is over.

When a mother has placenta previa (when a baby’s placenta covers the mother’s cervix), when a baby is in a breech (upside-down) position, when labor isn’t progressing at all, or when the umbilical cord may get pinched or compressed — C-sections, without a doubt, save lives. That’s why it’s a tragedy of maternal health that in certain areas of the world, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, C-sections are still out of reach.

The risks of an unnecessary C-sections

But according to Lancet, in cases where cesarean sections aren’t truly medically necessary, there are no health benefits for moms and only potential harms. The risk of maternal death and disability is higher after the procedure, recovery tends to be longer, and there’s a greater chance of complications in future births.

A woman’s bowels can get lacerated accidentally — and so can her child. Infections in the wound are a regular occurrence. And while vaginal birth is no cakewalk, it’s associated with “reductions in length of hospital stay, the risk of hysterectomy for postpartum hemorrhage, and the risk of cardiac arrest compared with planned [c-section],” according to the Lancet.

After a cesarean section, a woman is also at a greater risk of complications in future births — and with every C-section, these risks increase. For example, the rates of placenta accreta, a dangerous condition that can cause the placenta to grow out of control like a cancer, have exploded — because more women are getting the procedure.

The condition was exceedingly rare in the 1950s, occurring in only one in 30,000 deliveries in the US. Today, it shows up in about one in 500 births. One in 14 American women with accreta die, usually from excessive bleeding.

So if C-sections are an immensely serious surgery, with potential risks and complications for mom and baby, why do doctors do them so often?

Some people blame mothers (some of whom may be considered too old and too overweight to have normal births); others blame doctors, who might prefer to get out of the hospital before 5 pm instead of working through weekends and who receive higher reimbursements with C-sections.

But the story of the rise in C-section is a lot more complicated than that. As researchers pointed out in the Lancet, their explosion has “virtually nothing to do with evidence-based medicine.”

Why the C-section rate rose dramatically

There were 141 million babies born around the world in 2015, and 29 million of them — or 21 percent — started life with a C-section, according to the Lancet. Rates of the procedure have also skyrocketed in the last two generations of moms.

As for why, “some people argue moms looked different in the 70s than they do today,” Harvard’s Shah says. “There’s more obesity, moms are older, more hypertension and diabetes.”

But Shah has parsed the data, and found “this explosion” of C-section rates occurring in every demographic category. “They’ve gone up in young, healthy 18-year olds and in 35-year-olds,” he adds. “When you only look at only low-risk women, you see 15-fold variation” in rates of the procedure.

It’s also not that women are requesting more C-sections. According to a nationally representative survey, Listening to Mothers, only 3 percent of women elect to have the procedure because they are afraid of vaginal birth. “And there’s no health care service in the US that varies as much as this one: Cesarean rates by hospital go from 7 percent to 70 percent,” says Shah.

So after investigating the rise, he’s boiled the cause down to one thing: Over time, the cost for health care providers of waiting for a woman in labor has increased.

“If you are a clinician, you face the dichotomous choice — persist with a woman in labor whose labor has lasted longer than average, whose fetal heart monitoring is giving you an ambiguous reading,” he says, “or you can pull the rip cord.” Performing a C-section can offer a certain outcome through an uncertain process.

When it comes to cost, on average C-sections are reimbursed at 50 percent more than vaginal deliveries in the US, Shah says. Eighty percent of the cost of labor and delivery is staffing, and C-sections generally require a much small staff working for fewer hours. “So it’s not the additional money doctor makes. A vaginal delivery, from a resource point of view, just costs more.” These lower costs, and better reimbursements, are also found in other middle- and high-income countries.

Together, those two benefits of the surgery have far outweighed even the wishes of moms, though unlike Arnold, many moms don’t fight back. And they help explain why researchers have found that while C-sections driven by more objective criteria — like a baby being in a breech position — have been pretty stable over time, C-sections driven by less objective criteria — like a slow labor — have risen sharply.

How to stop the epidemic of unnecessary C-sections

Doctors are well aware of the unnecessary cesareans problem, and they’ve been studying ways to reduce them. Several approaches are described in the new Lancet series, including in a paper from the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics, as well as by the WHO:

- Hospitals need to address perverse incentives: If being reimbursed more favorably than vaginal births is driving the rise in C-sections, The Lancet argues “delivery fees for physicians for undertaking [the procedure] and attending vaginal delivery should be the same, using a mean fee.”

- Doctors need clear, evidence-based standards — and feedback: Since more subjective criteria — like a labor that’s going too long — are driving the rise in C-sections, the Lancet series also suggests standardizing exactly when C-sections should happen, and making sure physicians adhere to those standards and even seek out a second opinion before performing the surgery. The WHO recommends Cesarean audits — looking at doctors’ and nurses’ C-section rates, and why they decided to opt for the procedure — including giving feedback on those decisions.

- Hospitals should be transparent about C-section rates: The Lancet again: “Hospitals should be obliged to publish annual rates [of the procedure], and financing of hospitals should be partly based on c-section rates.”

- Midwives can help: They are trained to view birth as a normal process, and seek out ways to limit unnecessary medical interventions. And researchers have found the presence of more midwives and midwife-led units in hospitals correlates with fewer C-sections.

What women can do

If your doctor recommends a C-section, don’t panic; it may be completely appropriate. But unnecessary cesareans are a widespread problem, and there are some things women can do to reduce their chances of an unneeded procedure.

1) Ask what your provider and hospital are doing to promote vaginal birth. Christian Pettker, an associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at Yale School of Medicine, suggests asking questions like: Do you have criteria for admission to make sure a woman isn’t admitted too early? Do you do external cephalic versions to try and turn a breech baby around? Do you do vaginal births after C-sections? What criteria do you use for performing a cesarean if a woman’s labor is stalling? Hospitals that are addressing these issues — and have clear standards in place — are promoting vaginal births, he said.

2) Show up at the hospital as late as possible. “In movies, the depiction of labor is somebody breaks water, jumps into a car, runs red lights, and [the baby arrives],” Shah says. “Real labor takes hours. If you show up in active labor, you’re much less likely to get a Cesarean.”

3) Consider a midwife or supportive partner such as a doula who is experienced at serving as a coach during labor. “Places that rely more heavily on midwifes have fewer cesareans,” Declercq says. “They are trained not to intervene until it’s necessary.”

4) Research your hospital’s C-section rate: “The biggest risk factor [for a C-section] is not a woman’s personal risks — it’s what door you walk through,” Shah said. While a higher rate can mean the hospital is dealing with more complicated births, it might also be an indication of too many unnecessary surgeries.

There are also several sources that compare state- and hospital-level C-section rates. Jill Arnold was inspired to launch Cesareanrates.org, a website that tracks state-level data for women, after being pressured to have the procedure. The Leapfrog Group, a national non-profit focused on health care quality, has C-section rates for many hospitals across the US. Simply Googling and asking around at your local hospital might yield additional information.

“I didn’t anticipate that the need for CesareanRates.org would still exist in 2018. I was really banking on its eventual obsolescence,” Arnold said. For now, she wants to remind women that they can question a C-section recommendation. “It’s okay to say no and to ask what their doctor, midwife, or nurse thinks will happen if they wait and watch.”

Sourse: vox.com