This story is part of a group of stories called

Evidence-based explanations of the Covid-19 pandemic, including how it started, how it might end, and how to protect yourself and others.

The omicron variant has helped drive the United States into uncharted territory for the pandemic. The country was reporting an average of more than 400,000 new Covid-19 cases every day as of January 3, easily eclipsing last winter’s record of 250,000. And infections are still spiking, with the number of newly reported cases quadrupling since the beginning of December.

There is still a lot of uncertainty with the omicron variant: We’re still learning exactly how transmissible it is, how likely it is to cause severe disease and for whom. But we know more now than we did when it first began spreading in the US.

All the early indications were that omicron was even more transmissible than its predecessors, at least in part because of its ability to partially evade preexisting immunity, and that has proven to be true. While earlier CDC estimates that the variant took over in the US in mid-December turned out to be overstated, omicron now appears to have surpassed the previously dominant delta variant in its share of new US cases.

With cases rising, so is the number of patients in the hospital with Covid-19. But, at least so far, hospitalizations are not rising as rapidly as infections, lending credence to the theory that omicron leads to less severe disease, particularly for vaccinated people. Deaths have barely budged over the last month, with about 1,250 new deaths being reported every day as of January 3, essentially unchanged from the 1,125 daily average on December 3. While there is always a time lag between new reported cases and the data showing more serious illness, the evidence, including biological research findings, that omicron poses less of a threat to each individual patient is only growing.

But even if individuals face less risk from omicron, the variant still poses a danger and threatens to seriously disrupt daily life and the economy in the coming weeks.

The US could soon be averaging as many as 1 million cases every day. Workers and students will have to stay home when they test positive. The sheer speed of omicron’s spread is imperiling hospitals, already straining after two difficult years. Even if the proportion of omicron cases that turn serious is lower, some states are still seeing new highs in the number of patients in the ICU with Covid-19 because of how widespread omicron (and delta) cases are right now.

“The current omicron surge represents one of the greatest public health challenges not only of the pandemic but also of our lifetime,” Michael Osterholm and Ezekiel Emanuel, preeminent public health experts and two members of the Biden transition team, wrote in the Washington Post.

The two most important features of the omicron wave

Omicron’s extraordinary transmissibility has been evident since it was first detected in South Africa. But it had been an open question whether it would also be more dangerous to patients.

At this point, the evidence that omicron leads to milder illness, particularly for people with prior immunity, is solidifying. A lot of people are getting infected with the omicron variant right now, but at least so far, not as many of them are getting so sick that they end up in the hospital. The current US trends pointing toward less severe disease would align with how omicron has behaved in South Africa and the United Kingdom.

New York, one of the first omicron hot spots in the US, reflects the patterns nationwide and around the world: New cases have risen by nearly 300 percent over the last two weeks, but hospitalizations (up by 75 percent) and deaths (a 61 percent increase) have not seen the same exponential growth, though they are trending upward. California, likewise, has seen 400 percent growth in cases over two weeks, but less movement with hospitalizations (up 51 percent) and deaths (down 16 percent) over the same period. The share of their ICU beds occupied by Covid-19 patients has grown (up to 26 percent in New York and to 14 percent in California), but the percentage is still much lower than it was during the spring and summer waves of 2020, according to the University of Minnesota’s hospitalization tracker.

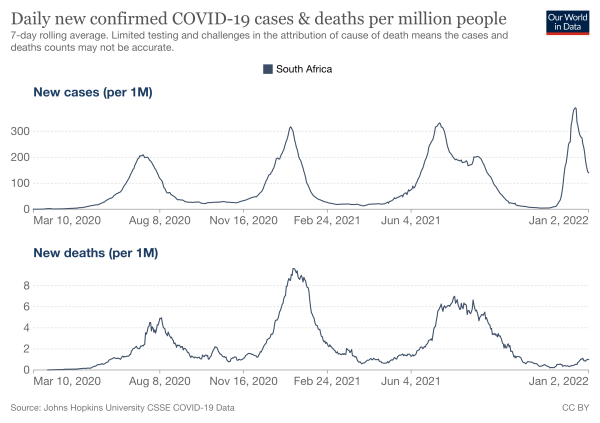

South Africa experienced rapid growth in new cases as omicron took hold, setting a new record of 23,300 every day by mid-December. But cases are now declining, and deaths have not come close to the highs seen over the summer and last winter.

The UK hasn’t seen a dramatic increase in deaths either, even as cases and hospitalizations are rising at a significant rate. Preliminary research from England and Scotland found that omicron was sending fewer people to the hospital than the delta variant did.

Early animal research points to why. In addition to the protection conferred by either vaccination or prior infection, omicron may not be as likely to cause severe symptoms that require hospital treatment. One study involving mice suggested that the variant does not penetrate as deeply into a person’s respiratory system. It is when an infection reaches the lungs that pneumonia can develop, and that’s what actually kills most people who die from Covid-19. Less penetration should lead to milder illness.

“These animal model data suggest the clinical consequences of infection with the Omicron variant may be less severe,” the authors wrote, “but the higher transmissibility could still place huge burden upon healthcare systems even if a lower proportion of infected patients are hospitalised.”

That is the Catch-22 of omicron: It is less likely to severely afflict people but spreads so rapidly that it will still endanger lives and seriously disrupt society and the economy.

Omicron still poses a serious threat to the US health system and economy

It’s a matter of math: The more people who get infected, the more likely it is the virus will spread to someone (whether unvaccinated or elderly or immunocompromised) who is more vulnerable to developing severe symptoms that require hospitalization.

Even if a smaller share of those people will die, thanks to vaccination or omicron being inherently less severe or new antivirals, hospitals may still become so full with Covid-19 patients that they don’t have enough staff or beds (or both) to care for everyone who needs that level of treatment.

Hospitals across the country report being overwhelmed, some reaching the crisis point where they don’t have the staff or physical capacity to treat every patient to the best of their ability, forcing difficult decisions about which patients they should prioritize. Even simply trying to distinguish omicron from the more severe delta variant in patients could become an obstacle to effective treatment. The conditions are only going to get worse if the number of hospitalizations keeps rising.

Already, some of the states experiencing the worst Covid-19 surges right now are seeing the outbreaks strain their hospitals as badly as ever. More than 35 percent of Ohio’s ICU beds are currently filled with Covid-19 patients, according to the University of Minnesota’s tracking project, matching the previous high seen in December 2020. Illinois and Pennsylvania also appear on pace to set new records in Covid-19 ICU patients. All three states are at or near their previous highs for all current Covid-19 hospitalizations.

What’s more, people who get infected are supposed to isolate for at least five days under the new CDC guidelines. That is shorter than the earlier 10-day recommendation, but could make staffing problems at hospitals even worse, further limiting their ability to care for all patients. In their Washington Post op-ed, Osterholm and Emanuel urged state and local governments to prepare for their health care workforces to be reduced by as much as 20 percent because infected doctors and nurses are isolating. (Recommended isolation times for health care workers who are infected were reduced, too, to seven days, or even fewer in emergencies.)

Other essential services outside the health system, such as police and fire, could also become understaffed because workers test positive and must isolate. Some schools are shifting to remote learning because of local Covid-19 surges.

The effect on the US economy with such widespread illness remains to be seen. Airlines canceled thousands of flights over the holidays because too many workers tested positive for Covid-19. Some economic analysts are speculating the US economy could contract in the first quarter of 2022 because of a depleted workforce and with many people exercising more caution to avoid omicron.

Osterholm and Emanuel proselytized a familiar playbook for reducing omicron’s spread and lightening the load, as much as possible, on the health system and other important services in the short term: masks, tests, and vaccines.

Vaccines can only do so much good now, with omicron already spreading rapidly and immunity taking several weeks to fully kick in. But wearing high-quality masks can still help prevent transmission. Testing if you think you’ve been exposed can help catch infections early and let you know to isolate to avoid spreading it to others. Experts have also urged people to continue testing after they get sick, only returning to normal activities once they test negative.

None of these interventions are going to stop omicron on their own; the variant is too contagious to be fully stopped. But they can still help, at a time when the stakes of slowing down Covid-19’s spread remain extremely high.

Will you support Vox’s explanatory journalism?

Millions turn to Vox to understand what’s happening in the news. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower through understanding. Financial contributions from our readers are a critical part of supporting our resource-intensive work and help us keep our journalism free for all. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today to help us keep our work free for all.

Sourse: vox.com