Wouldn’t it be better if self-checkout just died?

Yes! Because you won’t like what it spawns next.

By

Kaitlyn Tiffany@kait_tiffany

Oct 2, 2018, 7:00am EDT

Presented by

Share

Tweet

Share

Share

Wouldn’t it be better if self-checkout just died?

tweet

share

Rochester, New York, is a notorious model of terrible urban planning and idiotic corporate sponsorship. On the underdeveloped side of the Genesee River, next to the bus station, sits the “National Museum of Play,” an odd institution founded by Margaret Woodbury Strong — a Rochester native who inherited millions of dollars and used it to collect thousands of dolls.

The museum has rotating exhibits, but its centerpiece is an elaborate model of a Wegmans grocery store, sponsored by Wegmans, which is owned by the Wegmans family, which is the area’s sole billion-dollar dynasty.

In the mini Wegmans “Super Kids Market,” children select groceries (plastic produce, but real cereal boxes and genuine Chef Boyardee cans) from real grocery shelves, put them in real (miniaturized) Wegmans shopping carts, ring them up on functioning cash registers with real grocery scanners, and print themselves real receipts with a real Wegmans logo at the top.

It’s so fun. Pretend to work in a grocery store? Pretend to have money? Pretend you alone are in charge of what you eat and all you are going to eat forever is Cinnamon Toast Crunch and alphabet soup? Amazing.

But (for me, at least) that was the late ’90s. Far from novelty or spon-con child’s game, self-checkouts pop up everywhere now: at the new Target in Barclays Center where I buy my useless seasonal objects and knockoff Urban Outfitters clothes; at the CVS where I buy my disgusting seasonal candy; at the Panera Bread where I buy a seasonal autumn squash soup and half a grilled cheese. I’ve heard they are in grocery stores throughout the city, but I refuse to look.

I saw a self-checkout in the Urban Outfitters in Herald Square and almost called the ACLU: Some lucky employee sits on a stool near the self-checkout stations and does nothing but remove ink tags from things before you buy them? Sure. What is a person if not just a slightly more dexterous arm than the ones that robots so far have?

Blessedly, I am not alone in fearing self-checkout. John Karolefski, a self-proclaimed undercover grocery shopping analyst who runs the blog Grocery Stories and contributes to the site Progressive Grocer, tells me, “I’m in a lot of supermarkets around the country. I watch people. I can tell you that I’ve been in stores where the lines that have cashiers are very, very long, and people are a little upset, and there are three or four self-checkout units open and nobody is using them.

“Wouldn’t the shopper be better served, customer service improved, if those weren’t there?” he asks. I’m not arguing. “Why do I want to scan my own groceries?” he asks. I have no idea! “Why do I want to bag my own groceries?” he asks. An equally reasonable question with no reasonable answer. The simple solution, he points out, would be to hire enough cashiers to serve the number of customers that typically shop at the store. I agree, and this seems very obvious.

But before we get ahead of ourselves, let’s go back. To 1917, when Clarence Saunders opened the first grocery store — a Piggly Wiggly in Memphis, Tennessee — where customers were permitted to remove items from shelves and put them into a hand basket without the assistance of a clerk. He successfully patented this idea, called the “Self-Serving Store,” which is ridiculous. It took 60 years for the idea to move forward in a meaningful way, which it did when Florida business executive David R. Humble created (and patented) a self-service register and founded a company called CheckRobot in 1984.

Because it was a bad idea, it did not do very well. CheckRobot hemorrhaged money, then merged with a similarly flailing Jacksonville, Florida, software company in 1991. Kmart was the first big-box American retailer to add the company’s self-checkouts to its stores in 2001, and in 2003, it took them out.

K-Mart adopted self-checkouts in 2001, and in 2003, it took them out

A few more rounds of acquisitions and asset relocations brought Humble’s original idea into IBM’s hands in 2003, where it still didn’t find mass adoption. IBM is not even currently the major player in the self-checkout game — that designation goes to Atlanta-based National Cash Register Corporation, which survived a few juicy bribery scandals and one brush with violating US sanctions in Syria, and today boasts that it produces nine out of every 10 self-checkouts in the UK. (Its FastLane system is probably most familiar to Americans as the go-to at Walmart and Home Depot.)

Fujitsu, a Japanese tech company acquired by Montreal-based Optimal Robotics in 2004, supplies the systems you’ll see in major grocery store chains like Kroger (the largest grocer in the US), Harris Teeter (a popular Kroger sub-brand in the South), and, before its demise in 2015, the major Northeastern chain Pathmark (formerly part of ShopRite).

Each time a projection for future adoption rates of self-checkouts is made, it is wrong. In 2006, the same year Target was telling press that it had no plans to experiment with self-checkouts, IHL Consulting Group predicted there would be 200,000 self-checkout lanes in operation by 2007. There were only 191,000 by 2013. Experts then predicted that number would rise to 325,000 by 2019, but by 2016 there were only 240,000 and numbers were revised again. Most recently, the BBC has predicted there will be 468,000 by 2021. We’ll see, but there are still less than 300,000 worldwide right now, and seemingly everyone hates them.

That hatred can be explained in one phrase.

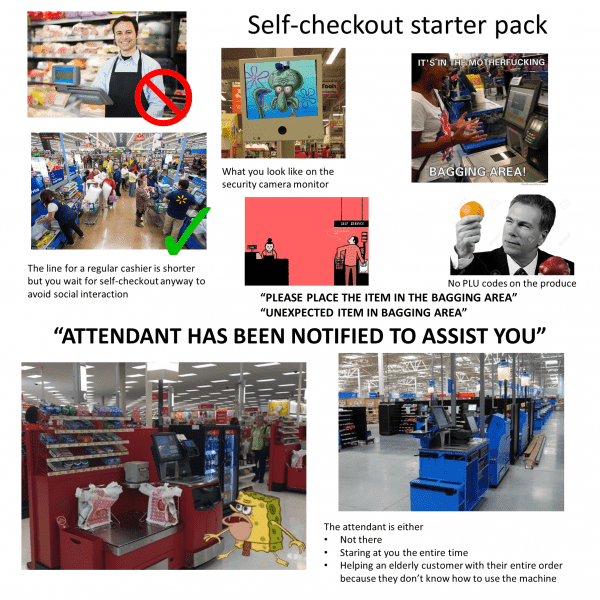

“Unexpected item in the baggage area” is a shared cultural reference like no other. It is recognizable by demographics so broad, the only thing that connects them is that they have at one point attempted to buy something at one of the nation’s largest grocery stores, pharmacies, or fast-food restaurants. It is fuel for memes, and tweets, and Reddit threads. It is the worst phrase known to retail. “Unexpected item in the baggage area” seems to be passive-aggressive code for “are you a shoplifter or just stupid?” and it haunts dreams. One Twitter user suggested that a good idea for a haunted house would just be a series of fake ghosts saying over and over, “Unexpected item in the baggage area.”

Anyone who has used a self-checkout has accidentally put something unexpected in the baggage area and been admonished. They’ve also forgotten to put something in the baggage area and been admonished. They’ve also done seemingly exactly what they were supposed to do and been admonished by some terrible robot nonetheless.

There have been attempts to make this serial berating more pleasant, such as when the UK supermarket chain Morrisons hired Wallace and Gromit actor Ben Whitehead to voice all of its commands, or when another UK supermarket giant, Tesco, decided that its machines should shout, “Ho, ho, ho, Merry Christmas!” in between each action, or when another British chain, Poundland, replaced all of its voice commands with instructions from an Elvis impersonator.

Stateside, we have made few vocal improvements, but Target did just replace all of its fruit and vegetable menus with emoji, so you can tap on a crying face to indicate that you would like to weigh and pay for an onion.

This constant frustration and humiliation is a contributing factor to the absolute stupidest thing about self-checkout, which is that a full 4 percent of the would-be sales that pass through them are not actually paid for.

Grocery stores have extremely tight profit margins, so that’s a big deal. (Again: We don’t have to do this!) People steal and steal and steal from self-checkout. They type in the price look-up code for bananas (#4011, for your reference) while far more expensive fruits or vegetables or even meat are on the scale. They pull stickers off cheap stuff and put them on expensive stuff. They are ingenious, as humans are when they want to do something that is against the rules. One Australian woman photocopied the barcodes from packets of instant noodles and printed them on sticky labels, which she then brought to the store with her every time she went shopping.

They are modern-day pirates without the violence; Walmart is their East India Trading Company.

Not everyone is trying to be a criminal mastermind. Anecdotally, a lot of people steal from self-checkouts simply because they get angry that an item won’t scan and figure it’s not their job to try that hard. Others steal small things here and there because the absence of a human cashier and the presence of only an obnoxious machine owned by a giant corporation turns it into a crime in name and not in spirit. University of Manchester criminology professor Shadd Maruna told the Guardian earlier this year:

The most comprehensive studies on stealing at self-checkouts have been published by Adrian Beck and his colleagues in the department of criminology at the University of Leicester, mostly in the past year. So I asked him, why so much stealing?

For one, he said, it’s easy to get away with and nearly impossible for police to get involved in.

“For retailers, this is a legal minefield — can they prove, beyond all reasonable doubt that you intended to permanently deprive them of the unscanned product?” he asked me in an email. I imagine not. “For the [self-checkout] user, they have what I call the ‘self-scan defense,’” he continued. “You simply apologize and say that you thought you had scanned the item. It is hard for the retailer to prove otherwise.”

And Beck echoes Maruna, saying self-checkout thieves can justify stealing by denying responsibility for the failure of the machines, and by telling themselves what they’re doing is not wrong: “The retailer is forcing me to scan my own items, something which used to be done by a paid employee, and therefore I deserve to be paid by taking some items for free.”

This guess is correct, at least in the words of some frequenters of the now-banned subreddit for shoplifting, which is preserved insofar as it has been quoted in news posts and other subreddits: “If you can’t afford to pay cashiers, I can’t afford to pay for my groceries.”

Self-checkout is frustrating in ways too diverse to name — the scanning mistakes, the messed-up barcodes, the odd rules. California state law changed in 2013, forbidding the sale of alcohol at self-checkouts, even those that stop the transaction and prompt an ID check by a store employee.

So, for the record: I would steal beer, in California.

As of 2016, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, more than 3.5 million Americans were employed as cashiers. The bureau’s 10-year forecast shows only a 1 percent reduction of these positions (just under 31,000 jobs), but this decrease has to be understood in the context of another trend: the rise of retail. The National Retail Federation says the sector grew nearly 4 percent last year and predicts it will do so again this year.

Beck tells Vox, “There are a number of reasons why retailers have invested in self-scan technologies. The first and most important is that it enables them to reduce their costs considerably. The largest proportion of a retailer’s cost is their wage bill.”

In one store, he added, he saw one supervisor tasked with overseeing 23 self-checkouts at once.

“The largest proportion of a retailer’s cost is their wage bill”

Walmart is the largest employer in the United States, and therefore defines what it means to be an American service worker. The company has a storied tradition of labor law violations, and a list of settlements longer than even a world-champion shoplifter’s haul diary, stemming from massive groups of workers alleging that they’ve been denied lunch breaks and overtime pay, illegally fired for participating in union activities, punished for taking medical leave, and held below the poverty line by an hourly wage rate that has barely budged since the 1980s. Now, Walmart will define what it means to be an American self-checkout supervisor.

“We look at what options can we provide for the customer,” Walmart director of corporate communications Ragan Dickens tells Vox. “What do they like? What are they responsive to? That’s where we begin the journey. We tested self-checkout in the early 2000s. They responded greatly, we piloted it in the early part of the decade, and now it’s in all of our stores.”

Dickens says that Walmart is piloting “large basket” self-checkout at one store somewhere on the East Coast, which will make it easier for customers to ring themselves up even when they’re buying a lot of items — even a cartful. It’s structured in a semicircle leading around the register, letting customers bag up their own purchases and load them back into their cart on the other side.

(The company recently discontinued its handheld self-checkout system, which was a success at Sam’s Club but a complete flop with Walmart customers.)

When I ask Dickens how Walmart will deter shoplifting at these huge new self-checkouts, he says the company has “some really neat technologies in place,” as well as cameras that reflect your face back to you, signs that warn people they’re under surveillance, and Walmart employees positioned within view. The neat technologies themselves are “not visible to the naked eye” and not up for discussion: “It’s not technology that we’re interested in going deeper on because bad guys watch the news too.”

Until self-checkout improves, surveillance like this is the solution. NCR, the biggest supplier of self-checkout technology, has said it is working on computer vision and facial recognition. In the meantime, Walmart and others are increasingly asking underpaid employees to spy extensively on the middle-class people they serve, with the goal of easing the way for the technology that will take their jobs.

Beck calls the elaborate system of cameras and designation of self-checkout “supervisors” and implementation of all these new, secret tracking measures “a surveillance web,” and he recommends it in a report he co-authored for the nonprofit consumer research group ECR Europe.

“Retailers should create ‘zones of control’ within which self-scan checkouts operate to ensure that potential thieves perceive it to be both difficult to steal and highly likely that if they did offend, they would be caught.” he wrote. This amounted to identifiable boundaries, a sense of order through “customer channeling,” locating self-checkouts away from exits, giving them single entry and exits points, and making special self-checkout supervisors — whose jobs are already terrible — wear “high visibility” outfits.

“Training of self-scan supervisors is critical,” Beck concluded. “They need to be aware of the importance of maintaining vigilance and keeping in close proximity to customers.”

Again, I have to ask — beg, really — why all this trouble? Why contort to shuck jobs and replace them with technology (which currently costs $30,000 to $60,000 per station to install) if nobody likes them, the security measures are another source of confusion and expense, and they’re eroding the relationship between retailer and consumer to the point where people feel they are morally obligated to steal?

Andrew Murphy, a managing partner at the venture capital firm Loup Ventures, thinks he has the answer for me.

“My quick take to answer your question directly is that self-checkout is a stepping-stone technology to true automated retail that will quickly get passed by.” He pauses. “Quickly may be the wrong word.”

Customers don’t want to do retailers’ jobs, he agrees. They’re smart enough to know that retailers are simply replacing cashiers with the customers themselves, training them to use simplified cash registers and eliminating cashier positions. He’s not saying this in any kind of moral outrage; he’s just stating the facts as someone who sometimes considers investing in new retail technology. (And he has recently, with Skupos, a data analytics firm that helps convenience stores more accurately stock their shelves and track inventory.)

“On a macro level, I just don’t love the space,” he says. The future is Amazon Go’s cashierless stores, which use cameras and machine learning and facial recognition and elaborate sensors to allow customers to simply pick up what they want and walk out. That kind of thing is “eventually going to win out over any kind of self-checkout that puts the onus on the customer.”

But what if Amazon keeps that technology to itself? Murphy says his firm believes the retail giant will license it out, in part to recoup the costs of developing it — and the reported $1 million a pop required to build the tech for the first test stores in Seattle, Chicago, and, soon, New York — but he admits they’re in the minority with that belief. “The obvious pushback is that retailers would never want Amazon to be their system of record for their inventory. They wouldn’t want Amazon cameras in their stores. But Amazon already is in tons of retailers, [through] Fulfillment by Amazon and Amazon Web Services.”

Anyway, if Amazon doesn’t sell its tech, that doesn’t even really matter. “I could list six Amazon Go competitors that are using similar camera vision or computer vision with cameras,” Murphy says. “Weight sensors, facial recognition, some combinations of those things.”

“I could list six Amazon Go competitors that are using similar camera vision or computer vision with cameras”

Murphy has heard startups claim that they can make setups similar to Amazon’s for as low as $10,000, which he thinks is probably off, but not by much. “Sometimes things are more complicated than an early-stage startup might try to convince you of, but it’s not going to cost $1 million like it did Amazon for long. Sometime in the next few years, it’ll really be 10,000 bucks for a retail store to implement some kind of automated solution. Which will be worth it, given the labor saving.”

He doesn’t think the extreme level of surveillance we’re talking about will be much of a problem either. We’re already surveilled. There will be pushback, but it will be from “a vocal minority,” and the proof of the technology’s success will be in its broad adoption.

“I tried Amazon Go in Seattle a few months ago,” Murphy says. “It’s awesome. Given the choice between that and a self-checkout kiosk, I think 99 customers out of 100 would prefer Amazon Go.”

In other words: Self-checkout isn’t an end in itself. It’s simply making us so frustrated with what we have that we’ll actually welcome the totally frictionless future of facial recognition and motion detection when it arrives.

The Strong National Museum of Play’s Wegmans Super Kids Market, obviously, is ridiculous, and I know that now. There is no need to teach children how to shop and buy things, as it is the one skill set we all pick up as naturally as we pick up breathing. Turning “play” into a giant advertisement (and, excuse me, covered in germs!) was deeply necessary and extremely creepy. Obviously!

(But also, as I said, the time of my life.)

Today, if you ask me to ring up my own groceries, I’ll tell you I’d rather have a Halloween-eve attic slumber party with 30,000 antique dolls.

Dystopian possibilities aside, what really stings about self-checkout is that right now it is not even automation, which has been so obviously deleterious to the job market but has also been, for the most part, successfully framed as progress. Self-checkout is sold to us as a high-tech upgrade, but that’s just adding insult to injury — eliminating jobs by making people who have jobs do more jobs. When Walmart installs a new self-checkout, it’s not “automating” the process of checkout; it’s simply turning the register around, giving it a friendlier interface, and having the shopper do the work themselves.

In a Reddit thread about a Wegmans in downtown Rochester adding self-checkout stations, one user commented, “As a customer, what a privilege it will be to work at, even for the briefest moments, the Fortune 100 2nd-best company to work for!”

Wegmans Super Kids Market was delightful because I, like every child, enjoyed a good game of make-believe; the self-checkout lanes at the new, real Wegmans in downtown Rochester will be delightful because Wegmans will tell us they are. Capitalism loves to cast things as play that are not play. It is wildly talented at making us think things are getting easier, and that we’re all having just the best time. Really, we’re just waiting in line to fuck it up and fuck each other over.

Want more stories from The Goods by Vox? Sign up for our newsletter here.

Sourse: vox.com