2020 Democrats’ campaign finance pledges, explained

Democratic presidential candidates are rejecting special interest campaign donations. But there is usually a catch.

By

Dylan Scott@dylanlscott

Updated

Jun 24, 2019, 4:20pm EDT

Graphics by Javier Zarracina/Vox

Share

Tweet

Share

Share

2020 Democrats’ campaign finance pledges, explained

tweet

share

Democrats running for president in 2020 are making a big show of turning away top-dollar donors. Most of these campaign finance pledges sound good, and they are certainly better than not making such a promise. But these are not necessarily airtight safeguards against money buying influence with presidential candidates.

“For years, candidates for both parties publicly declared support for limiting money’s influence on politics but then privately exploited every campaign finance loophole they could find,” Brendan Fischer, director of federal reform at the Campaign Legal Center, says. “We’re in an entirely different environment this cycle, and I think that’s a good thing.”

Corporate PACs, something every Democrat running for president has sworn off, tend to provide a relatively small chunk of the money, Fischer told me. So turning down their support probably isn’t going to hurt a candidate’s bottom line too much. Rejecting PAC money also isn’t the same as rejecting support from high-level executives.

“The no-corporate-PAC pledge is popular. It’s a symbolic expression of a candidate’s commitment to reform,” Fischer says. “But it may not make a huge dent in their fundraising.”

Turning down support from federal lobbyists also isn’t as simple as it sounds. Many people in Washington who try to influence lawmakers and policy are not actually registered as lobbyists with the government. Influential people can still give to candidates without the campaigns having violated that pledge. Fischer gave the example of former Vice President Joe Biden attending a fundraiser with Comcast’s David Cohen, who oversees the telecom giant’s lobbying shop but isn’t registered as a lobbyist himself.

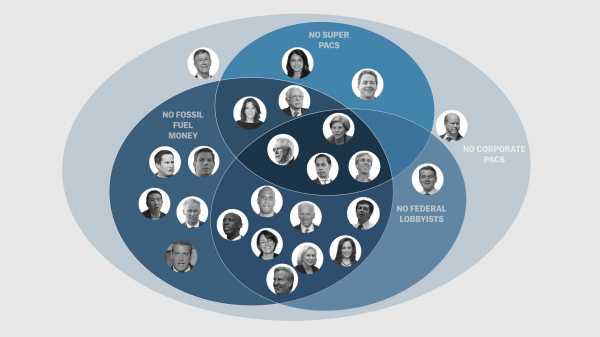

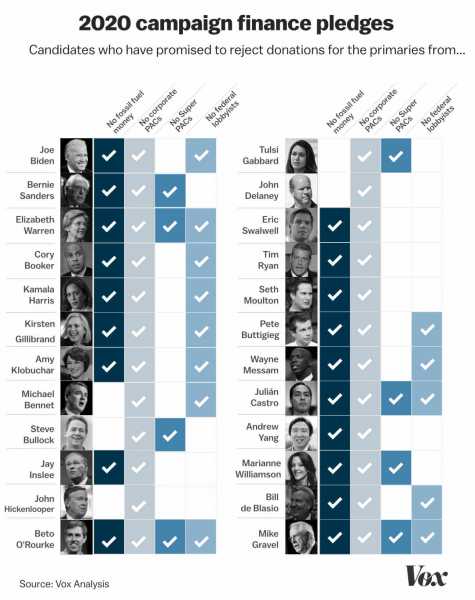

Still, the very fact that candidates feel they need to make these pledges is real change. Vox surveyed all 24 Democratic presidential campaigns and received responses from all 24 of them. Every campaign that responded to us said it was refusing donations from corporate PACs. Most also said they were rejecting support from the fossil fuel industry and from registered federal lobbyists. A handful of them are forgoing support from Super PACs of any kind. Two candidates — Sens. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren — have sworn off high-dollar private fundraisers.

“The pledge that seems the most meaningful is the one that eschews closed-door big-money fundraisers and donor perks,” Fischer says. “One way wealthy donors can have a broader influence on politics and politicians is at fundraisers. We kind of take it for granted wealthy donors can buy access.”

The loopholes in these pledges — and the willingness of many Democratic candidates to solicit donations from elite, wealthy donors — is a reminder of how difficult the problem of money in politics will be to fix. But the Democratic field’s renunciation of certain streams of major campaign donations is still a sign of progress.

What the 2020 Democratic campaigns have actually promised on donations

Vox asked every Democratic campaign to provide the promises they had made regarding which industries, groups, and people they would not accept financial support from. The inquiry was intentionally open-ended. Every campaign provided a response.

The promises generally covered four kinds of donations: from the fossil fuel industry, from corporate PACs, from all Super PACS, and from federal lobbyists.

Note: Cory Booker’s campaign followed up after this story was published and said he also doesn’t accept support from Super PACs. The graphics will be updated soon.

Here are the raw tallies:

- 24 campaigns are rejecting donations from corporate PACs

- 19 campaigns are rejecting donations from the fossil fuel industry

- 13 campaigns are rejecting donations from federal lobbyists

- 9 campaigns are rejecting donations from all Super PACs

Some of the campaigns added other entities to their blacklist. Biden isn’t accepting money from “unions, federal contractors, national banks or foreign nationals.” South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg also rejects donations from the pharmaceutical industry. California Rep. Eric Swalwell doesn’t want support from “the NRA or tobacco industry.” New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio specified any lobbyists or businesses that do business with New York City in his response.

The official No Fossil Fuel Money pledge pushed by anti-climate change grassroots organizers, signed by 16 candidates (Biden’s campaign said he would not accept support from the industry but he is not listed as a signatory of the pledge), is self-explanatory. With climate change as the greatest threat to humanity’s future, Democratic candidates are shunning the industry that voters hold responsible for it. Rejecting corporate and federal lobbyist money is a signal of a candidate’s willingness to ignore the traditionally influential interests in Washington.

But the reality, of course, is a little more complicated.

The potential loopholes in these 2020 campaign finance pledges

Some of these pledges can still be subverted. Disavowing corporate (fossil fuel or otherwise) PAC money does not mean disavowing support from individual CEOs and executives, though some campaigns added them to their pledge. There are plenty of people in Washington who still wield influence and persuade officials without actually being registered as lobbyists.

Closed-door, high-dollar fundraisers remain perhaps the most pernicious means of influence in modern-day politics, and most of the Democratic candidates have still been participating in those, as the Washington Post’s Michelle Ye Hee Lee recently documented.

But even there, a few candidates stand out: Warren has promised she will not attend any exclusive gatherings like that as part of her platform to weed out corporate influence in US politics. Sanders has also disavowed any high-dollar private events and any donor perks.

“I’m not taking a dime of PAC money in this campaign. I’m not taking a single check from a federal lobbyist. I’m not taking applications from billionaires who want to run a Super PAC on my behalf. And I challenge every other candidate who asks for your vote in this primary to say exactly the same thing,” Warren said when announcing her candidacy.

Even the no-Super PAC promise isn’t perfect; Cory Booker said he didn’t want Super PAC support, but a wealthy Democratic donor started one backing his candidacy anyway. And because of the rules prohibiting coordination between campaigns and Super PACs, there technically wasn’t much Booker could do about it.

Those soft spots are why Fischer regards the rejection of closed-door, high-dollar fundraisers as the gold standard for campaign finance pledges. Even if we were to give candidates the benefit of the doubt, their attendance at those private events where participants had to spend thousands of dollars to join is going to skew — intentionally or not — their views on what issues are important and what should be done about them.

“The only people inside can write a $2,800 check. They get face time with the candidates. The candidate spends an inordinate amount of time with donors, hearing about their concerns and pitching themselves as someone who is going to be responsive to those concerns,” Fischer says. “Even the best-intentioned candidate is going to be affected by that.”

Joe Biden’s recent comments reassuring donors that “nothing will fundamentally change” for wealthy people under a Biden presidency were made at a fundraiser; his campaign does allow press to cover those events, however.

Warren and Sanders were the only candidates to swear off such events in their response to Vox. The one private event that the Vermont senator held had tickets available for $27, the Washington Post reported, not a huge barrier for middle- or working-class voters who want to attend.

The evidence shows that campaign donations buy access and policy outcomes

These days, “quid pro quo” corruption is pretty rare, Fischer emphasized. Politicians and moneyed interests are simply too savvy to get caught making a specific offer of money for a specific deed.

But campaign contributions can still buy big donors access to elected officials. It’s not just common sense and anecdotal evidence that prove it, either. Empirical research has shown what some well-placed donations can get you.

A 2016 paper from two University of California Berkeley researchers, published in the American Journal of Political Science, ran a remarkable experiment. A political organization tried to schedule meetings with 191 congressional offices between lawmakers and their campaign donors. For some of the requests, the group disclosed that the donor had given money to the campaign; for other requests, they withheld that crucial information.

It was a truly randomized experiment. This is what it yielded (emphasis mine):

Other studies have found a similar connection. Researchers from Stanford and the University of Wisconsin examined campaign donations from corporations to members of congressional committees that affect their business. They found industries would drop donations to members who were leaving an influential committee and instead direct their money to incoming members, even those of the opposite party.

“We provide evidence that corporations and business PACs use donations to acquire immediate access and favor,” the authors wrote, “suggesting they at least anticipate that the donations will influence policy.”

The Roosevelt Institute ran its own data, examining the behavior of lawmakers who initially voted in favor of the Dodd-Frank financial reform bill and then took later votes to weaken the bill’s provisions, and found that “for every $100,000 that Democratic representatives received from finance, the odds they would break with their party’s majority support for the Dodd-Frank legislation increased by 13.9 percent.”

Sometimes, it doesn’t require any academic rigor at all to see how money influences policy. Rep. Chris Collins (R-NY) said before the Republican tax bill passed in 2017 that his donors had told him to pass the bill, legislation that would hit his home state harder than most, “or don’t ever call me again.”

The pressure on Democratic campaigns: ideals versus practical needs

Ever since Citizens United allowed corporations and rich donors to write blank checks to support their chosen political activities and candidates, Democrats have sworn that they will do whatever they can to put a check on money buying access in politics. The pledges the 2020 candidates have made demonstrate commitment to that goal.

But Democrats often find these promises hard to keep. In prior elections, presidential and otherwise, Democrats accepted Super PAC support while decrying its influence. They defended that compromise by arguing Republicans had no such qualms about allowing big donors to boost their campaigns. Indeed, defeating President Donald Trump remains at the top of Democrats’ agendas — and they may care a lot less about how such a campaign is funded. They don’t want to fall behind in an arms race; Trump has already raised more than $150 million for his 2020 reelection campaign.

The expansive nature of the 2020 Democratic primary field has put new pressure on these pledges. The Washington Post reported recently that Beto O’Rourke, who previously swore off any private fundraisers, had held an exclusive event with maxed-out donors. Buttigieg, Gillibrand, Klobuchar, O’Rourke, and Bennet might disavow corporate PAC money but they have still attended closed-door events with donors in Manhattan or the San Francisco Bay Area in recent weeks, according to the Post.

Some of these candidates are finding there simply isn’t enough grassroots support to fuel their presidential campaigns. As the Post’s Michelle Ye Hee Lee summarized her findings:

It’s easy to promise you’ll turn off the spigot of big money — until you find yourself choosing between an underfunded campaign and compromising on your ideals. This is the same dilemma Democrats always find themselves in on large campaign donors: They don’t want them, but they think they need them.

Money has a way of grinding down even the best intentions. While 2020 has been an improvement on past election cycles, it still might end up another chapter in that age-old tale for many of its campaigns.

Sourse: vox.com