Warning: This story may be upsetting to children who believe in Santa Claus.

Reindeer are perhaps best recognized by their magnificent antlers, the largest of any deer species in proportion to their bodies. They’re also notable for their epic thousand-mile journeys every year in search of food, in herds of 100,000 or more.

And they’re supremely important to the Arctic ecosystem as a source of food and livelihood for local people, and because of their power to reshape vegetation by grazing.

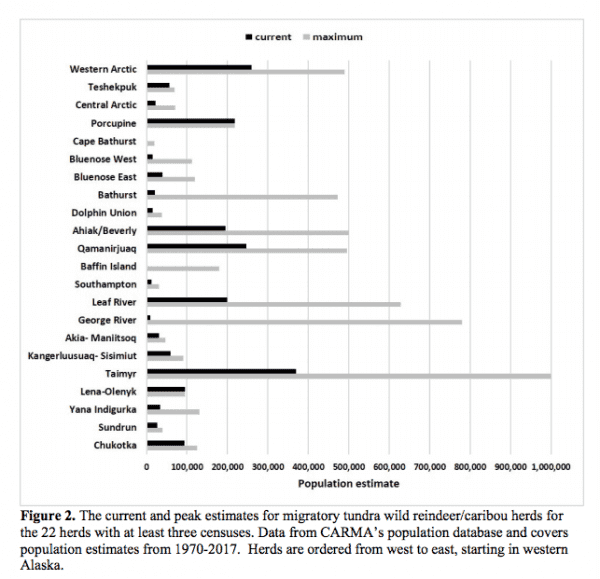

But the populations of reindeer, a.k.a. caribou, near the North Pole have been declining dramatically in recent years. Since the mid-1990s, the size of reindeer and caribou herds has declined by 56 percent.

That’s a drop from an estimated 4.7 million animals to 2.1 million, a loss of 2.6 million.

“Five herds,” out of 22 monitored “in the Alaska-Canada region, have declined more than 90 percent and show no sign of recovery,” according to the latest Arctic Report Card from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, out Tuesday. “Some herds have all-time record low populations since reliable record keeping began.”

Herds have lost hundreds of thousands of individuals, as measured by aerial photography of herds and counts in areas where caribou give birth. And their declines affect not just the landscape but the people who depend on it. The report explains that the declining number of animals are “a threat to the food security and culture of indigenous people who have depended on the herds.“

Big swings in population size aren’t a shock

Reindeer and caribou are the same animal. They are members of the species Rangifer tarandus. The Rangifer tarandus that live in North America are called caribou, and the ones in Europe and Siberia are called reindeer. Mostly they are wild creatures, but sometimes they are domesticated to pull sleds and carriages.

Ecologist Don Russell, the lead author of the report subsection on caribou, says it’s normal for herd sizes to fluctuate greatly. It’s part of a natural cycle: Herds can go from numbers in the hundreds of thousands to the tens of thousands in just a few decades, and then rebound.

“The fact that these herds are declining shouldn’t be a shock — they do it all the time,” Russell said by phone from the Yukon territory in Canada. “But they’re at such low levels, you start to be concerned. … If we return in 10 years and [their numbers] have gone down further, that would be unprecedented.”

The question now, he says, is “are their numbers so low they can’t recover?”

Climate change means the future of caribou, like that of so many other creatures, is uncertain

The herds have been declining in recent decades due to a complicated mix of factors including hunting, disease, diminished food availability, and climate change, the report explains.

On one hand, you’d think that with climate change, the Arctic would become a more favorable environment for these grazing animals. Longer, warmer summers mean more vegetation for them to nosh on. And according to the Arctic Report Card, the Arctic did grow greener between 1982 and 2017.

But it seems the warmer Arctic summers are also taking a toll on the reindeer. “Warmer summers also have adverse effects through increased drought, flies and parasites, and perhaps heat stress leading to increased susceptibility to pathogens and other stressors,” the report notes. Higher summer temperatures and wintertime freezing rain (as opposed to snow) seem to be correlated with adult caribou morality.

Warmer summers have also meant that diseases, long locked in the Arctic permafrost, may thaw and spread among herds, though scientists aren’t completely sure how much of an impact this is having.

And warmer winters can hurt them too. When it rains in the Arctic, as opposed to snow, it can freeze over into ice. That makes it harder for the caribou to walk, and to eat. In 2013, 61,000 (61,000!) reindeer died of starvation in Russia due to excess ice. Currently, a lack of snow in Sweden is impeding reindeer migrations there.

As the climate warms, and as freezing rain replaces snow in the far north, this threat may increase.

Animal populations are shrinking worldwide

The change in caribou numbers also looks concerning when you factor in what’s happening to wildlife around the world.

In October, WWF, the international wildlife conservation nonprofit, released its biennial Living Planet Report, a global assessment of the health of animal populations all over the world. The topline finding: The average vertebrate (birds, fish, mammals, amphibians) population has declined 60 percent since 1970.

That eye-popping figure — a 60 percent decline in average populations — is not the same as saying the world has lost 60 percent of its animals. But most populations of animals, like particular herds, or schools of fish, have seen declining numbers.

There’s a bigger global story here that we must reckon with: Humans are a small part of the living world, yet we have an outsize impact on it. The WWF report stresses that wildlife faces multiple threats — climate change, habitat loss, pollution, hunting, and invasive species — which all trace back to us and our insatiable consumption patterns.

What we lose if we lose the caribou

Caribou don’t have the ability to fly. (Sorry, kids. Though, if you’re reading a science news article, you probably know this by now.) But they’re hugely important to the Arctic ecosystem as a source of food for predators like wolves and biting flies. “A lot of the ecosystem components are riding on their backs,” Russell says.

Moreover, they’re central to the traditions of indigenous people in the Arctic, like the Sami, as a source of food and clothing. “If you look at the [top] Northern resources, that shape the culture of northern communities and aboriginal people, what they have in common is caribou and or wild reindeer, no matter where they are in the circumpolar North,” he says.

The takeaway is that the Arctic landscape is changing — and it’s changing more dramatically than anywhere on the Earth. The temperature increase in the Arctic just since 2014, the report card also finds, “is unlike any other period on record.” And it’s not yet clear if the caribou can change and adapt with it.

Sourse: vox.com