Finding the best ways to do good. Made possible by The Rockefeller Foundation.

President Donald Trump and Congress may be on the verge of passing actual bipartisan legislation that would ever so slightly ease mass incarceration — after Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell on Tuesday announced that he will allow a vote on the measure this month.

The bill, known as the First Step Act, would take modest steps to reform the criminal justice system and ease very punitive prison sentences at the federal level. It would affect only the federal system — which, with about 181,000 imprisoned people, holds a small but significant fraction of the US jail and prison population of 2.1 million.

The bill has come a long way since it was introduced earlier this year, when it passed the Republican-controlled House of Representatives. Back then, the bill made no effort to cut the length of prison sentences on the front end, although it did take some steps to encourage rehabilitation in prison that inmates could use, in effect, to reduce how long they’re in prison. But Senate Democrats and other reformers took issue with the bill’s limited scope, and eventually managed to add changes that will ease, albeit fairly mildly, prison sentences.

So although the bill would have already allowed thousands of people to earn an earlier release from prison, it would now let thousands more out of prison early, and could cut many more prison sentences in the future.

Even though Trump ran on a “tough on crime” platform in which he promised to support harsh prison sentences, the president has come to support the legislation — in large part thanks to the backing of key advisers, including son-in-law Jared Kushner. And the bill now has support from a wide array of groups, including the American Civil Liberties Union, the Koch brothers–backed Right on Crime, and other organizations on both the left and right.

That doesn’t mean the bill has skated by without opposition. Some Senate Republicans, led particularly by Sen. Tom Cotton of Arkansas, have taken issue with the mild reforms in the First Step Act, even as Republican senators like Chuck Grassley (IA) and Lindsey Graham (SC) have come on board.

That opposition seriously endangered the bill: With Congress in the last few days of its current session, and with other legislative priorities on the calendar, McConnell had indicated that he may not allow the bill to come up for a vote — because he feared that lawmakers just wouldn’t have enough time to work out their differences without causing serious rifts within the Republican caucus.

But McConnell, on Tuesday, said that the legislation will move forward.

What comes next remains to be seen. But at this point, the First Step Act is the closest Congress has gotten to passing significant criminal justice reform in years.

What the First Step Act does

Here are the major provisions of the First Step Act, as it stands now:

- The bill would make retroactive the reforms enacted by the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, which reduced the disparity between crack and powder cocaine sentences at the federal level. This could affect nearly 2,600 federal inmates, according to the Marshall Project.

- The bill would take several steps to ease mandatory minimum sentences under federal law. It would expand the “safety valve” that judges can use to avoid handing down mandatory minimum sentences. It would ease a “three strikes” rule so people with three or more convictions, including for drug offenses, automatically get 25 years instead of life, among other changes. It would restrict the current practice of stacking gun charges against drug offenders to add possibly decades to prison sentences. All of these changes would lead to shorter prison sentences in the future.

- The bill would increase “good time credits” that inmates can earn. Inmates who avoid a disciplinary record can currently get credits of up to 47 days per year incarcerated. The bill increases the cap to 54, allowing well-behaved inmates to cut their prison sentence by an additional week for each year they’re incarcerated. The change applies retroactively, which could allow some prisoners — as many as 4,000 — to qualify for release the day that the bill goes into effect.

- The bill would allow inmates to get “earned time credits” by participating in more vocational and rehabilitative programs. Those credits would allow them to be released early to halfway houses or home confinement. Not only could this mitigate prison overcrowding, but the hope is that the education programs will reduce the likelihood that an inmate will commit another crime once released and, as a result, reduce both crime and incarceration in the long term. (There’s research showing that education programs do reduce recidivism.)

Not every inmate would benefit from the changes. The system would use an algorithm to initially determine who can cash in earned time credits, with inmates deemed higher risk excluded from cashing in, although not from earning the credits (which they could then cash in if their risk level is reduced).

But algorithms can perpetuate racial and class discrimination; for instance, an algorithm that excludes someone from earning credits due to previous criminal history may overlook that black and poor people are more likely to be incarcerated for crimes even when they’re not more likely to actually commit those crimes. So although the bill would put checks on the algorithm, it’s turned into a controversial portion of the bill even among criminal justice reformers.

The bill would also exclude certain inmates from earning credits, such as undocumented immigrants and people who are convicted of high-level offenses.

And it would make other changes aimed at improving conditions in prisons, including banning the shackling of women during childbirth and requiring that inmates are placed closer to their families.

All of this is subject to change, however, as Congress continues to debate the bill.

Nothing in the legislation is that groundbreaking, particularly compared to the state-level reforms that have passed in recent years, from reduced prison sentences across the board to the defelonization of drug offenses to marijuana legalization. That’s one reason the bill is dubbed a “first step.” Still, it would be a step — the kind that Congress hasn’t taken in years, as it’s debated criminal justice reform but ultimately failed to do it.

Some Senate Republicans threatened the bill

Supporters of the First Step Act claim that the bill would get at least 70 votes, out of 100, in the Senate if it were put up to a vote today.

But the bill has been mired by vocal opposition from some Senate Republicans. For a while, it looked like that opposition might win — until McConnell agreed to bring the legislation to a vote.

The opposition to the bill comes primarily from Sen. Cotton. In tweets and articles about the legislation, Cotton has said that he has several concerns about the bill, arguing that it would allow violent and high-level drug offenders out of prison early and make it far too easy to earn an early release from prison.

The bill’s supporters argue that Cotton is either misunderstanding the bill or misleading the public about it.

For example, Cotton claimed that “productive activities” are defined so vaguely in the bill that federal inmates could earn early release by watching TV or doing other leisurely activities. But Sen. Mike Lee (R-UT), one of the legislation’s supporters, countered that the early release programs “are designed by federal prison wardens, not prisoners. Federal prison wardens simply do not award time credits for watching TV. Furthermore, the bill mandates data analysis on the effectiveness of each recidivism-reduction program. If the program is not proven effective, wardens will not award time for participating in it.”

Cotton has also claimed that some high-level offenders would be eligible for early release under the bill, because it doesn’t exclude, for example, someone convicted of threatening to assault, kidnap, or murder a judge from earning time credits. But Jessica Jackson Sloan, the national director and co-founder of the criminal justice reform group #Cut50, argued that this misunderstands how the law is applied in reality: Someone convicted of threatening to kidnap a judge would also be convicted on kidnapping charges more generally — and those general charges would lead to exclusion under the First Step Act.

Cotton “should know better than a lot of the arguments he’s putting out there,” Sloan told me.

In reality, Cotton is simply opposed to criminal justice reform. He has argued that America actually has an “under-incarceration problem” — even though the US has by far the highest incarceration rate in the world. From his perspective, stiffer prison penalties deter crime, keeping Americans safe.

This goes against the empirical evidence on the topic, which has consistently found that more incarceration and longer prison sentences do little to combat crime. A 2015 review of the research by the Brennan Center for Justice estimated that more incarceration — and its abilities to incapacitate or deter criminals — explained about 0 to 7 percent of the crime drop since the 1990s, though other researchers estimate it drove 10 to 25 percent of the crime drop since the ’90s.

Another huge review of the research, released last year by David Roodman of the Open Philanthropy Project, found that releasing people from prison earlier doesn’t lead to more crime, and that holding people in prison longer may actually increase crime.

That conclusion matches what other researchers have found in this area. As the National Institute of Justice concluded in 2016, “Research has found evidence that prison can exacerbate, not reduce, recidivism. Prisons themselves may be schools for learning to commit crimes.”

The First Step Act starts to chip away at this problem at the federal level, although its overall impact is unlikely to be very large.

Even if the bill passes, its effect on mass incarceration will be relatively small

The bill still faces an uncertain road through Congress. But assuming it passes, even its most ardent supporters acknowledge that it will have a fairly small impact on the size of the federal prison system and particularly the national landscape. The bill may let thousands of federal inmates out early, but, as Stanford drug policy expert Keith Humphreys noted in the Washington Post, more than 1,700 people are released from prison every day already — so the bill in one sense only equates to adding a few more days of typical releases to the year.

One major reason for the bill’s limited scope: It deals only with the federal system, which is a fairly small part of the overall criminal justice system in America.

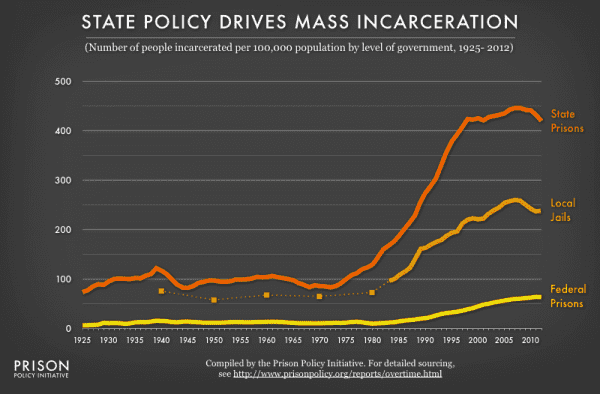

Consider the numbers: According to the US Bureau of Justice Statistics, 87 percent of US prison inmates are held in state facilities (and most state inmates are in for violent, not drug, crimes). That doesn’t even account for local jails, where hundreds of thousands of people are held on a typical day in America. Just look at this chart from the Prison Policy Initiative, which shows both local jails and state prisons far outpacing the number of people incarcerated in federal prisons:

One way to think about this is what would happen if President Donald Trump used his pardon powers to their maximum potential — meaning he pardoned every single person in federal prison right now. That would push down America’s overall incarcerated population from about 2.1 million to about 1.9 million.

That would be a hefty reduction. But it also wouldn’t undo mass incarceration, as the US would still lead all but one country in incarceration: With an incarceration rate of around 593 per 100,000 people, only the small nation of El Salvador would come out ahead — and America would still dwarf the incarceration rates of other developed nations like Canada (114 per 100,000), Germany (75 per 100,000), and Japan (41 per 100,000).

Similarly, almost all police work is done at the local and state level. There are about 18,000 law enforcement agencies in America, only a dozen or so of which are federal agencies.

While the federal government can incentivize states to adopt specific criminal justice policies, studies show that previous efforts, such as the 1994 federal crime law, had little to no impact. By and large, it seems local municipalities and states will only embrace federal incentives on criminal justice issues if they actually want to adopt the policies being encouraged.

Criminal justice reform, then, is going to fall largely to municipalities and states, and a bill that might slightly cut incarceration on the federal level isn’t going to have a very big effect. (To this end, many cities and states are actually way ahead of the federal government when it comes to criminal justice reform, with many passing the kinds of sentencing reforms that the federal system has struggled to enact.)

That’s not to downplay the work of criminal justice reformers who are trying to reduce the size and burden of what amounts to a fairly large prison system at the federal level. But to understand the bill, it’s important to put its full impact on mass incarceration in the broader national context.

For more on mass incarceration, read Vox’s explainer.

Sign up for the Future Perfect newsletter. Twice a week, you’ll get a roundup of ideas and solutions for tackling our biggest challenges: improving public health, decreasing human and animal suffering, easing catastrophic risks, and — to put it simply — getting better at doing good.

Sourse: vox.com