Paul Bartels gets a rush every time he discovers a new species of tardigrade, the phylum of microscopic animals best known for being both strangely cute and able to survive the vacuum of space.

”The first paper I wrote describing a new species, there was a maternal-paternal feeling — like I just gave birth to this new thing,” he said in 2016.

The rush comes, in part, because tardigrades are the most fascinating animals known to science, able to survive in just about every environment imaginable. ”There are some ecosystems in the Antarctic called nunataks where the wind blows away snow and ice, exposing outcroppings of rocks, and the only things that live on them are lichens and tardigrades,” says Bartels, an invertebrate zoologist at Warren Wilson College in North Carolina.

Pick up a piece of moss, and you’ll find tardigrades. In the soil: tardigrades. The ocean: You get it. They live on every continent, in every climate, and in every latitude. Their extreme resilience has allowed them to conquer the entire planet.

And though biologists have known about tardigrades since the dawn of the microscope, they’re only just beginning to understand how these remarkable organisms are able to survive anywhere. Biologists like Bartels have been studying more than 1,000 species of tardigrade worldwide, trying to reverse-engineer their remarkable ability to survive. Here’s what they’ve learned so far.

1) First things first: Tardigrades are uncannily cute

Tardigrades seem like the type of animal Pixar would feature in a life-affirming yet heart-wrenching children’s movie. “They’re very charismatic,” Bartels says.

Just look at one and you’ll see why.

Tardigrades — which grow up to a millimeter in length — swim with four sets of stubby legs that appear much too small for their bodies. At the end of each leg is a set of stubby little claws. Tardigrades lumber around in the water, like a bear might when crossing a river. Hence their nickname, “water bears.”

Tardigrades can move their heads independent of their bodies, and some species have eyes. When you look at them under the microscope, they stare straight back, unfazed by humans.

2) Tardigrades can transform into tuns — allowing them to survive just about anywhere

Most microscopic animals need water to survive — otherwise, they can evaporate away if taken out of the water.

But not tardigrades.

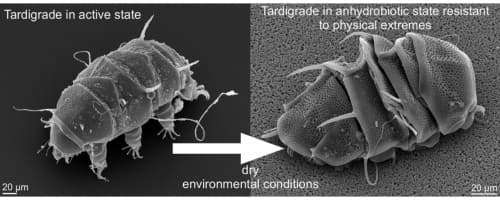

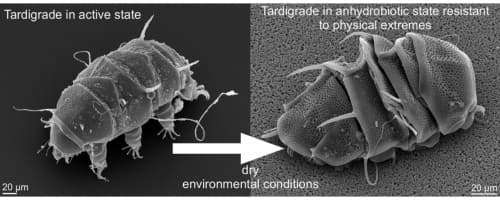

When removed from water and dried out, tardigrades can transform into a cellular fortress, tucking in their legs and head, forming a compact pill shape called a “tun.”

In this tun state, the tardigrades produce glycerol (antifreeze), and also secrete trehalose, a simple sugar with remarkable preservation properties. “Trehalose is viewed as a cocoon that traps the biomolecule inside a glassy matrix, like amber-encasing insects,” explains a 2009 paper in Protein Science. When the trehalose crystalizes, the tardigrade becomes mummified in a glass suit of armor.

This process is called vitrification, and scientists have been trying to replicate it for use in protecting other delicate cellular tissues like sperm and eggs.

In this state of hibernation, the tuns can withstand just about any assault. Boiling water and temperatures near absolute zero (i.e., as cold as cold gets) don’t faze them.

In 2007, the European Space Agency launched a satellite carrying (among other things), a payload of tardigrades in tun form, and selectively exposed them to the vacuum of space and cosmic radiation. Ten days later, the tardigrades were returned to Earth and rehydrated. Remarkably, a handful of them survived both the radiation and the vacuum, making them the first animals on record to survive complete space exposure.

Research has also shown the tuns can survive pressures up to 87,022.6 pounds per square inch — six times what you’d find in the deepest part of the ocean. (Around 43,00 PSI, “most bacteria and multicellular organisms die,” Nature reported.)

As a tun, the tardigrade reduces its metabolism by 99.99 percent as it waits for a more suitable environment. There have even been reports of tuns surviving more than 100 years before rehydrating.

In 1983, a team of Japanese scientists on a journey through Antarctica collected some tardigrades and put them in a deep freeze for thirty years. When the tardigrades unfroze in May 2014, they did not seek vengeance upon humanity for their imprisonment. Instead, they moseyed around on a plate of agar gel like nothing had happened. And then they reproduced.

Watch them reawaken below:

Tardigrades have different adaptations for a wide variety of environmental threats. In hot conditions, they release heat-shock proteins, which prevent other proteins from warping. Some tardigrades can form bubbly cysts around their bodies. Like puffer jackets, the cysts allow them to survive in harsh climates without having to revert into full tun mode.

And scientists are hoping to learn how to mimic these remarkable adaptations for other organisms. (There’s some small evidence that inserting a tardigrade protein into human cells helps protect the human cells from radiation.)

Tardigrades are sometimes referred to as ”extremophiles,” a term used to describe super-hardy bacteria that can live on ocean vents and other extremely inhospitable environments. Bartels clarifies that they are not extremophiles, as they don’t really “live” and move around in tun mode. “It’s very easy to kill them when they are out and about in their normal environment,” Bartels says.

But in their tun form, they are extremely difficult to kill. And, in the aftermath of a cataclysm like an asteroid impact, they’d likely be the last living things on Earth. To kill all the tardigrades on Earth, the authors of a 2017 Nature’s Scientific Reports paper argued, it would take an event with enough power to vaporize all of the oceans. So expect tardigrades to survive to the bitter end of the Earth.

3) They have sex for an hour

If we know all that about how tardigrades protect themselves from threats, we ought to know how they mate, right? Right?

“Although tardigrades have been studied for almost 245 years and by now more than 1200 species have been described, there are only a few publications concerning the life-history or mating behavior of tardigrades,” researchers at Germany’s Museum of Natural History Görlitz explain in the Journal of Zoological Systems and Evolutionary Research wrote in 2016.

So the researchers set out to correct the gap in the science, filming 30 tardigrade couples copulating for a first-of-its-kind study.

The result: For the first time published in a scientific journal, here’s a video of two tardigrades getting it on.

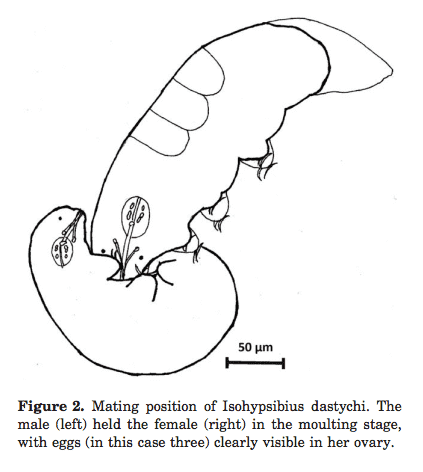

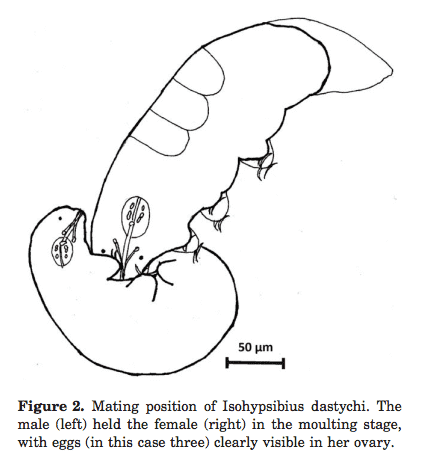

Yeah, it’s a little hard to see what’s happening. Luckily, the scientists drew a cartoon diagram to help. Basically, the male (at the bottom of the diagram and on the right-hand side of the GIF) curls up around the female’s head and holds himself there with his front legs. The female then stimulates the male “by moving her stylets [mouth-like openings] and contracting the sucking pharynx [the throat],” according to the study authors.

The scientists note the whole process takes about an hour, during which “semen [is] ejaculated several times.” Now we can add marathon copulation to the list of this animal’s impressive abilities.

4) Tardigrades are often the first to pioneer new ecosystems

Byron Adams, a Brigham Young University biologist, explains that tardigrades often are the first to colonize new, harsh environments. They act as the founding links in food chains.

An example: “When a volcano erupts, and molten lava pours over everything in the ecosystem, everything in that ecosystem is dead,” he writes in an email. “Tardigrades are among the very first multicellular animals to colonize. The tardigrades feed on the microbes that live in this environment.” The tardigrades, in turn, accumulate the essential elements for life — such as nitrogen, carbon, and phosphorus — that then allow plants and other life forms to move in.

Adams has conducted fieldwork in Antarctica, studying how melting permafrost will impact the microscopic ecosystem there. Because tardigrades are ubiquitous, they’re likely to play a role in how the Antarctic continent changes with a warming climate.

”They set the stage for other organisms,” Adams said in 2016. “They created the niches in which other more complex organisms evolved. And I think that’s totally cool.”

5) Just about anyone can discover new tardigrade species

Because tardigrades can survive any environment, they have proliferated across the globe. If you pick up a rock in you backyard, there are probably some tardigrades living underneath it. Though more than 1,000 species have already been identified, more are being discovered every year.

One of Bartels’s undergraduate classes discovered a new species on the coast of South Carolina. The class voted to name the species after spaghetti — just because they could. “They got real excited,” Bartels said.

Carleton College has a handy field guide to find tardigrades . Just five easy steps! You can purchase a super-cheap pocket microscope that attaches to a cellphone camera to view them.

6) Did we mention they’re oddly cute?

Sourse: vox.com