Today, humans inhabit almost every corner of the earth. But why?

Our dispersal can be traced back to a group of humans who left Africa sometime around 50,000 years ago. Anyone not purely of African ancestry is related to these people.

These humans, however, were not the first to venture outside of Africa. They’re just the only ones we know of who survived and produced offspring.

The slow, gradual migration of humans across the world wasn’t easy, and wasn’t necessarily inevitable. For tens of thousands of years, people ventured out of Africa, lived for a while, and then, mysteriously, disappeared.

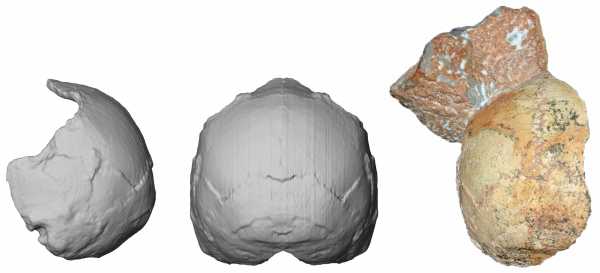

Paleoanthropologists now claim to have found the oldest fossil specimen belonging to one of these groups of early explorers. In a new study in Nature, researchers in Europe and Australia report that an analysis of a skull fragment — called Apidima 1 — found in a Greek cave in the 1970s belongs to a Homo sapiens living around 210,000 years ago, as measured by radioactive dating. The next-oldest fossil from a Homo sapiens, some teeth and a piece of jaw, is 177,000 to 194,000 years old and was found in Israel, so this one is considerably older.

If the authors of the new Nature paper are correct, it could potentially push back the timeline of when humans first left Africa, as Greece is farther away from Africa by foot than Israel. It’s also possible this group and the one found in Israel all came from the same common ancestor. Exciting new findings in anthropology often open up more questions than they answer.

But the fossil described in the new paper may not be enough to persuade everyone of this hypothesis. It’s a single piece of skull, which the researchers then digitally reconstructed into a full skull. “The fossil at issue is very incomplete, and I suspect that many will not consider it entirely diagnostic of Homo sapiens,” says Ian Tattersall, a paleoanthropologist and an emeritus curator with the American Museum of Natural History in New York who was not involved with the new research.

So some paleoanthropologists may be skeptical about whether this fossil truly did come from Homo sapiens (the fossil has a distinct roundness that is only found in Homo sapiens, the study authors find). But if it did, the finding invites us to wonder about what unfolded in the early years of our species’ time on earth.

Related

The story of human evolution in Africa is undergoing a major rewrite

Also in this Nature paper, the authors report that another specimen found in the same cave, called Apidima 2, belonged to a Neanderthal, but one who lived 170,000 years ago. It’s possible that both groups — Neanderthals and early humans — lived in this region during an overlapping period of time. (And we know, at least later on, that humans and Neanderthals mated. These groups could have as well.)

“This finding reveals that at least two species of hominin (humans and human relatives from the branch of the family tree after our split from chimpanzees) inhabited southeastern Europe approximately 200,000 years ago,” Eric Delson, a paleoanthropologist at Lehman College, writes in a commentary, also published in Nature Wednesday. It used to be more commonly thought that Neanderthals had settled in Europe, died out, and then were replaced by humans. Now it appears there was a lot more overlap in the two species on the continent. (It’s believed the ancestors of the Neanderthals entered Europe around 500,000 years ago.)

Related

Humans and Neanderthals had sex. But was it for love?

And the questions generated from that idea are fascinating. For instance: Why did some of these early modern humans die out in Europe? Did Neanderthals push them out? Was there fighting? Were they not well enough adapted to the colder climate during the ice age that covered much of Europe in glaciers? And then why wasn’t it until 50,000 years ago that humans really flourished outside of Africa?

“We don’t have the answers to these questions, and we don’t have the evidence to answer them,” Katerina Harvati, the University of Tübingen anthropologist who led the study, says.

It’s all in service of the basic question: Why are we here? And why has human history unfolded in the way it has?

Perhaps the findings speak to a deeper piece of human nature: The instinct to explore new lands, not knowing the risk or if it will be successful, goes back a very long way.

Sourse: vox.com