On Wednesday, January 31, the full moon will pass through the shadow of the Earth. For 77 minutes, the usually silvery moon will be covered with a blood-red/ochre shadow.

Even more notable: This total lunar eclipse will happen during the second full moon this month — a bonus event known as a “blue moon.” Such a coincidence (and it is nothing more than a coincidence) has not occurred in 150 years. Topping things off, this moon will be a “supermoon,” meaning it will appear slightly bigger and brighter than average.

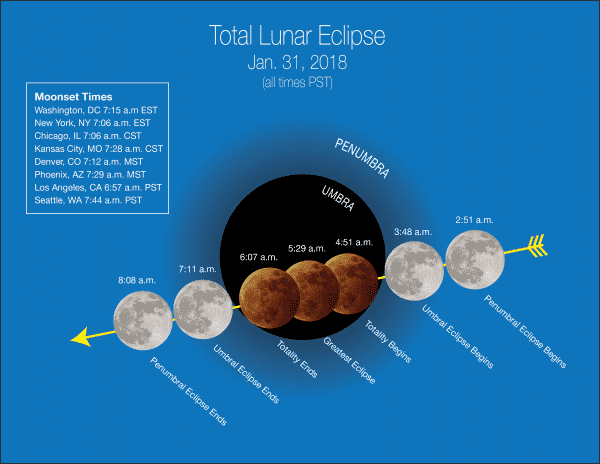

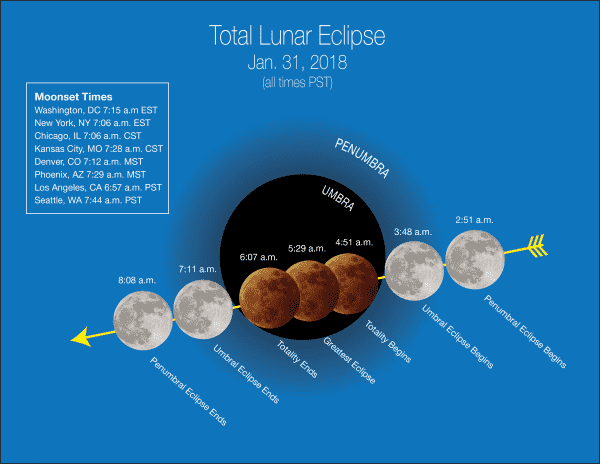

It’s an impressive trifecta — but not everyone will be able to see the full show. Much of the East Coast of the United States will only see a partial lunar eclipse of the blue moon just before and during dawn. The best time to look for it is at 6:48 am ET (sunrise is at 7:15 am). Worse is that just before dawn, the moon will be near the horizon in the western sky. If you live in a wooded area, in a city, or anywhere with an obstructed view of the horizon, it will be hard to spot.

West Coasters will be able to see the full eclipse but will have to be up at 4:51 am PT to catch it. The Midwest has a shot too. In St. Louis, Missouri, people can check out the total eclipse just before sunrise, at 6:51 am CT. Alaska and Hawaii will have the best view in the United States. In Honolulu, the total eclipse begins at 2:51 am local time; in Anchorage, it begins at 3:51 am. (Check out TimeandDate.com to see when you might be able to catch a glimpse of the eclipse in your area.)

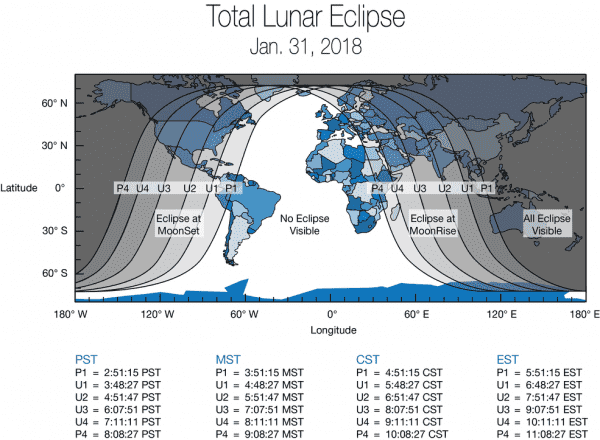

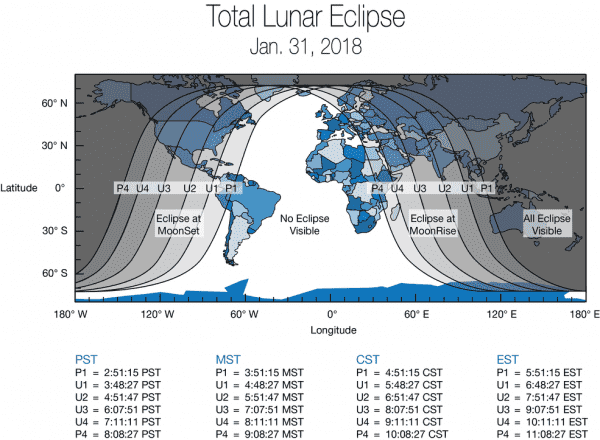

Much of South America, Africa, and Europe will, alas, be out of luck; the moon will have already set for the evening by the time it passes through the Earth’s shadow. (During a full moon, the moon sets when the sun rises, and vice versa.)

Here’s a map of all the places in the world that should be able to see the eclipse (if it’s not too cloudy out).

Why do we have lunar eclipses?

The simple answer is “because the moon sometimes passes through the shadow of the Earth.” But there’s more to it than that.

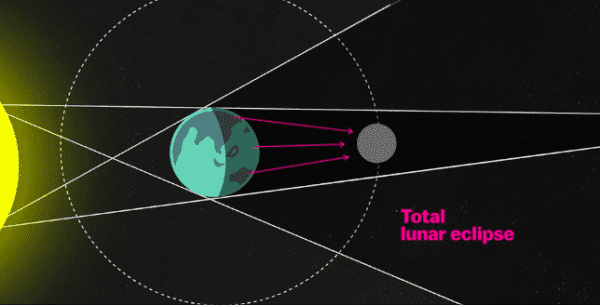

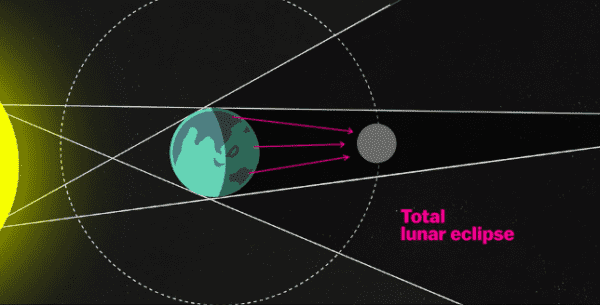

For one, it has to be a full moon. When the moon is full, it means the sun, Earth, and moon are in alignment, like so:

Now, you might be thinking: “Why don’t we have lunar eclipses every full moon?”

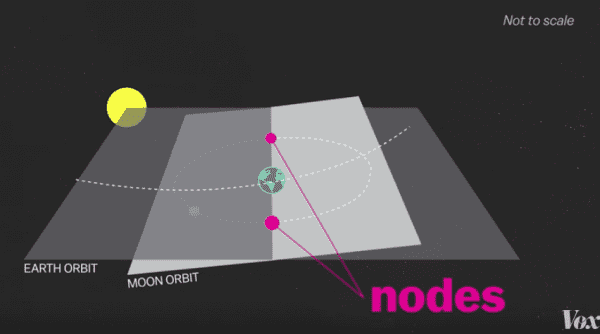

The moon’s orbit isn’t perfectly matched up with Earth’s. It’s tilted 5 degrees:

No one is completely sure why — but it might have to do with how the moon was likely formed: from a massive object smashing into Earth.

This means during most full moons, the shadow misses the moon, as you can see in the diagram above.

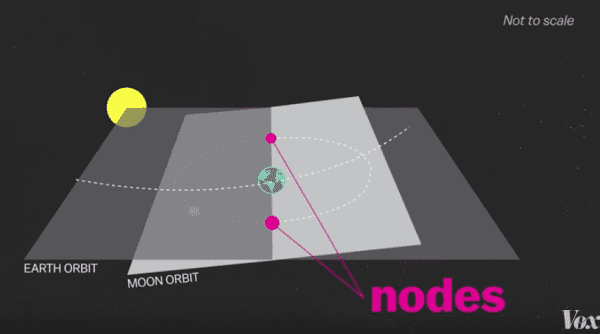

There are two points in the moon’s orbit where the shadow can fall on the Earth. These are called nodes.

For a total eclipse to occur, the moon needs to be at or very close to one of the nodes.

When the sun, Earth, and moon are aligned at a node, voila! The moon falls into the path of the Earth’s shadow.

There are usually two or three lunar eclipses in given year (the next one is July 27, but North America will not see it.)

Everyone lucky enough to be on the night side of the Earth during a lunar eclipse is able to witness it. You don’t need any special equipment or protective glasses to view it (unlike the total solar eclipse). But a pair of binoculars will give you a better, more detailed view of the moon’s geography as it darkens in shadow.

What’s a “blue moon”?

Confusingly, “blue moon” has two definitions. It can mean:

- A second full moon within a calendar month. This happens once every two or three years.

- The third of four full moons during a particular season (fall, winter, spring, or summer). Usually, there are only three full moons in a particular season. This happens once every 2.5 years.

In either case, “blue moon” means “extra moon.” It does not mean the moon appears to be blue (which can happen, but the atmosphere needs to be loaded with a lot of volcano dust and debris).

It’s the result of the lunar calendar and our earthbound calendar being slightly out of phase. A lunar month, as measured by the time it takes to go from one full moon to another — a “synodic month” — is 29.5 days long, while most calendar months are 30 or 31 days long. As a result, the lunar year is only 354 days. The solar year is 365.25 days long.

What does this mean for my horoscope?

Nothing. Astrology isn’t real. It is a pseudoscience bent on making big to-dos out of insignificant coincidences.

What’s a supermoon?

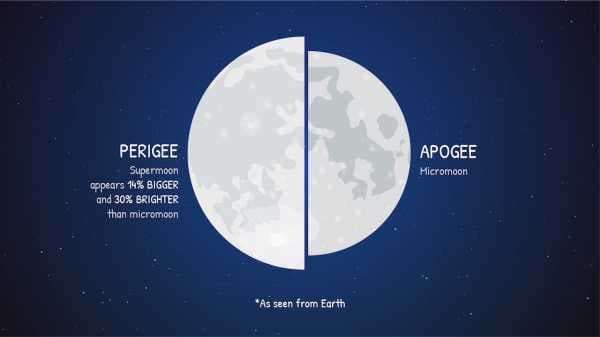

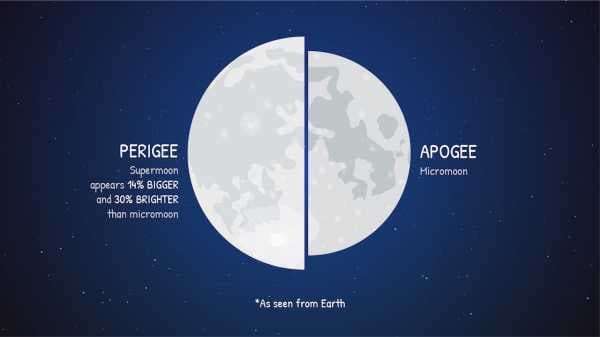

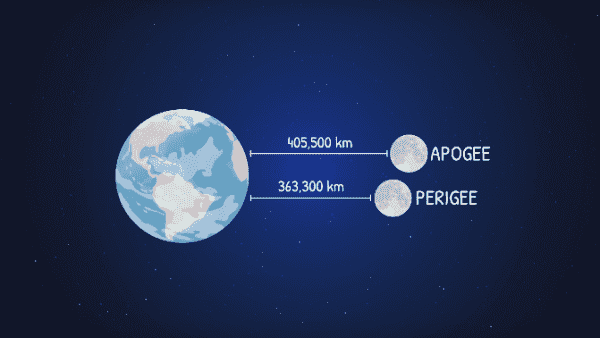

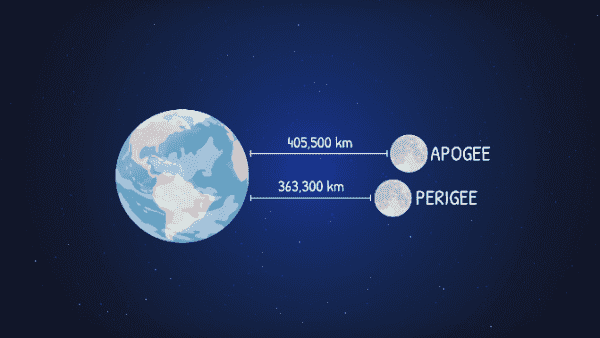

The moon’s orbit around Earth is not a perfect circle. It’s an ellipse, a saucer shape that’s longer than it is wide. As the moon follows this orbit, it’s sometimes closer to the Earth and sometimes farther away. At perigee, the closest spot in its orbit to the Earth, it’s around 31,068 miles closer to Earth than at apogee, when it’s farthest away.

Meanwhile, we see different phases of the moon — full, crescent, waxing, and waning gibbous — depending on if the sun-facing side of the moon is facing the Earth.

A supermoon is when these two cycles match up and we have a full moon that’s near its perigee. The result is that the full “super” moon appears slightly larger and slightly brighter to us in the sky. This occurs about one in every 14 full moons, Jim Lattis, an astronomer at the University of Wisconsin Madison, notes.

The difference between a normal full moon and a supermoon isn’t all that much. Neil deGrasse Tyson has called the frenzy around supermoons overblown. “If you have a 16-inch pizza, would you call that a super pizza compared with a 15-inch pizza?” he said on the StarTalk radio show. For the most part, NASA explains, the differences between a normal full moon and a supermoon “are indistinguishable” to the human eye.

The supermoon doesn’t have any astronomical significance other than making for a slightly larger target for backyard astronomers to look at.

Why does the moon turn red during a lunar eclipse?

During a total solar eclipse — like the one North America saw last summer — the entire brighter-than-bright disc of the sun turns black, revealing the sun’s atmosphere.

What happens during a total lunar eclipse is a bit less dramatic, but beautiful nonetheless.

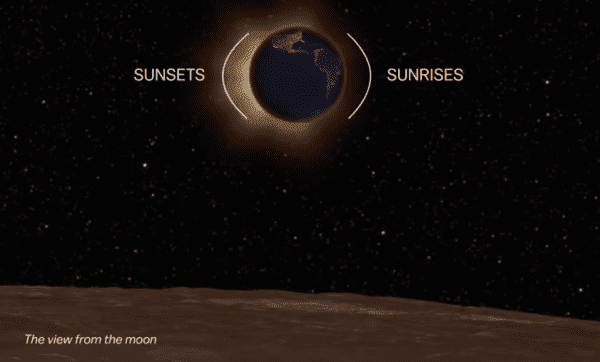

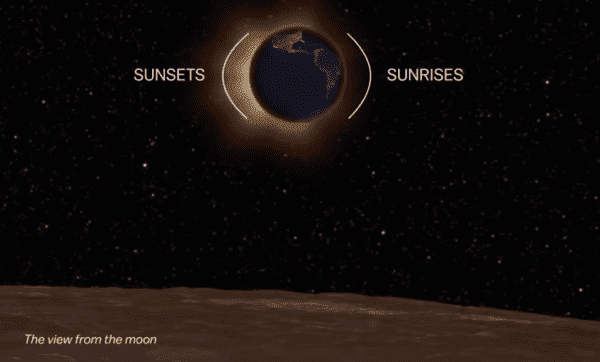

When sunlight passes through the atmosphere, the gases therein trap and scatter the blue light in the spectrum. (This is why the sky appears blue.) The red, orange, and yellow wavelengths pass through into Earth’s shadow and get projected onto the moon.

Basically, as Vox’s Joss Fong has explained, a total lunar eclipse is like projecting all the sunsets and sunrises onto the moon.

Is that something worth waiting up until 4:51 am on the West Coast for? Arguably, yes.

The best view, however, might be from the moon itself (good luck getting there). The moon around you would go dark. Look up toward the Earth and you’d see a smoldering ring of sunlight form a halo around our home world, illuminating the atmosphere in warm sepia. Here, NASA illustrates what it might look like.

Watch: Eclipses, explained

Sourse: vox.com