President Donald Trump will nominate William Barr as his next attorney general — and criminal justice reformers are very worried.

The news means Barr, who formerly served as President George H.W. Bush’s attorney general, will replace former Attorney General Jeff Sessions if the Republican-controlled Senate approves Trump’s nomination. (Matthew Whitaker is currently serving as acting attorney general.)

Much of the attention is focused on what Barr’s nomination may mean for the Russia investigation, given his previous remarks that he thought it was okay for Trump to fire FBI Director James Comey and that Hillary Clinton should be investigated.

But as head of the US Department of Justice, Barr would also have a lot of control over the federal criminal justice system more broadly. Ames Grawert, senior counsel at the Brennan Center, which supports criminal justice reform, tweeted, “Barr is one of the few people left in policy circles who could reasonably be called as bad as, or worse than, Jeff Sessions on criminal justice reform.” And make no mistake: Sessions had a very bad record on criminal justice reform.

In fact, Barr praised Sessions’s record at the Justice Department, including some of his work dismantling criminal justice efforts by President Barack Obama’s administration.

In short: If you were hoping that Sessions’s replacement would be better on criminal justice reform, Barr’s nomination should be of great concern.

Bill Barr’s punitive record on criminal justice issues

Barr doesn’t just have a record of supporting the war on drugs and mass incarceration. As attorney general for George H.W. Bush, he was one of the architects for federal policies that supported both.

Here are some examples, noted in part by Grawert, of Brennan, and civil rights lawyer Sasha Samberg-Champion:

- As deputy attorney general from 1990 to 1991 and attorney general from 1991 to 1993, Barr pushed for and helped implement more punitive criminal justice policies, including a 1990 crime law that, among other things, escalated the war on drugs.

- In 1992, Barr signed off on a book by the Department of Justice titled The Case for More Incarceration. In a letter of support, Barr argued that “there is no better way to reduce crime than to identify, target, and incapacitate those hardened criminals who commit staggering numbers of violent crimes whenever they are on the streets.” He also called on the country to build more jails and prisons. (Although he specified violent criminals, the federal system, unlike the much larger state systems, locks up mostly drug offenders.)

- In 1992, asked about racial disparities in prisons by Los Angeles Times reporter Ronald Ostrow, Barr argued that “our system is fair and does not treat people differently.” He went on to defend laws that made prison sentences for crack cocaine much harsher than prison sentences for powder cocaine. The disparity between the two was reduced by the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, in part because there’s little justification for it based on the drugs’ effects, but the higher sentence for crack has a disproportionate racial impact since crack was more commonly used in black communities and powder cocaine was more commonly used in white communities.

- In 1994, Barr co-chaired a commission for Virginia’s governor that released a plan to abolish parole (which allows certain inmates to go free before the completion of their sentences) in the state, increase prison sentences, and build more prisons.

- Barr also once said that it was “simply a myth” that there were “sympathetic people” and “hapless victims of the criminal justice system” in prisons, according to David Krajicek at Salon.

It’s possible that Barr’s views have evolved since then, just as many people’s views have toward the drug war and mass incarceration, particularly as crime has plummeted in the past two decades.

But that doesn’t seem to be the case. Just last month, Barr and two other former attorneys general wrote an op-ed for the Washington Post in which they defended Sessions’s “tough on crime” record. They criticized the Obama administration for investigating police abuses and discouraging more aggressive policing practices. They also praised Sessions for his memo encouraging federal prosecutors to pursue harsher prison sentences against drug offenders.

The research doesn’t support mass incarceration

Barr’s support for more punitive criminal justice policies goes against the research, which has found that more incarceration and longer prison sentences do little to combat crime.

A 2015 review of the research by the Brennan Center for Justice estimated that more incarceration — and its abilities to incapacitate or deter criminals — explained about 0 to 7 percent of the crime drop since the 1990s, though other researchers estimate it drove 10 to 25 percent of the crime drop since the ’90s.

Another huge review of the research, released last year by David Roodman of the Open Philanthropy Project, found that releasing people from prison earlier doesn’t lead to more crime, and that holding people in prison longer may actually increase crime.

That conclusion matches what other researchers have found in this area. As the National Institute of Justice concluded in 2016, “Research has found evidence that prison can exacerbate, not reduce, recidivism. Prisons themselves may be schools for learning to commit crimes.”

In fact, Trump seemed to acknowledge this research when he came out in support of the First Step Act, which would, among other reforms, ease some federal prison sentences. Sessions was reportedly opposed to the bill — and based on Barr’s record, he might be too.

The silver lining: the federal criminal justice system isn’t that big

If there is any sign of optimism for criminal justice reformers here, it’s that the federal criminal justice system is a relatively small part of the national criminal justice system.

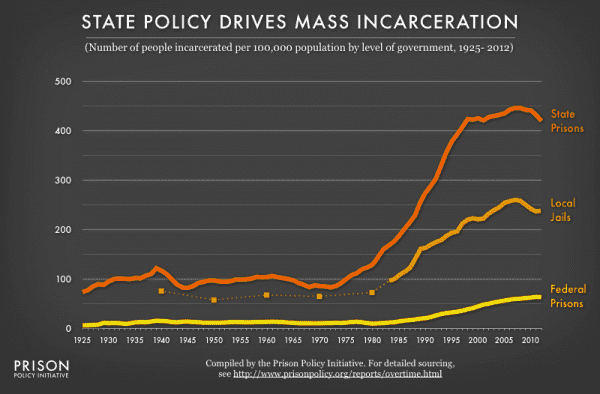

Consider the numbers: According to the US Bureau of Justice Statistics, 87 percent of US prison inmates are held in state facilities (and most state inmates are in for violent, not drug, crimes). That doesn’t even account for local jails, where hundreds of thousands of people are held on a typical day in America. Just look at this chart from the Prison Policy Initiative, which shows both local jails and state prisons far outpacing the number of people incarcerated in federal prisons:

One way to think about this is what would happen if President Donald Trump used his pardon powers to their maximum potential — meaning he pardoned every single person in federal prison right now. That would push down America’s overall incarcerated population from about 2.1 million to about 1.9 million.

That would be a hefty reduction. But it also wouldn’t undo mass incarceration, as the US would still lead all but one country in incarceration: With an incarceration rate of around 593 per 100,000 people, only the small nation of El Salvador would come out ahead — and America would still dwarf the incarceration rates of other developed nations like Canada (114 per 100,000), Germany (75 per 100,000), and Japan (41 per 100,000).

Similarly, almost all police work is done at the local and state level. There are about 18,000 law enforcement agencies in America, only a dozen or so of which are federal agencies.

While the federal government can incentivize states to adopt specific criminal justice policies, studies show that previous efforts, such as the 1994 federal crime law, had little to no impact. By and large, it seems local municipalities and states will only embrace federal incentives on criminal justice issues if they actually want to adopt the policies being encouraged.

Criminal justice reform, then, is going to fall largely to municipalities and states. To this end, many local and state governments are actually way ahead of the federal government when it comes to criminal justice reform, enacting changes like reduced prison sentences across the board, the defelonization of drug offenses, and marijuana legalization in recent years.

So Barr may represent another grim few years for criminal justice reformers at the federal level. But they’ll still have plenty of opportunities in cities, counties, and states, which hold way more sway in the overall justice system.

Sourse: vox.com