California’s newly elected governor Gavin Newsom kicked off his campaign in 2017 with a bold promise to tackle the state’s housing supply crisis by creating 3.5 million new housing units by 2025. That would mean nearly quadrupling the pace at which the state issues permits for new housing units. The goal should be achievable considering the market price of California houses, but would require very ambitious changes to the way housing permitting works in the state.

As a candidate, Newsom did not embrace a specific framework to achieve the promise. But State Sen. Scott Wiener (D) from Newsom’s home city of San Francisco is out with a new version of sweeping housing legislation that failed last year as SB-827 but has now been reformulated (and renamed SB-50) in ways that should address some of critics’ concerns about displacement of existing renters. It also appears to have broadened the political coalition behind the bill.

During Jerry Brown’s last couple of years in office, California already took significant steps to start addressing the state’s housing crisis — steps that on their own could be game-changers for several American states. But California’s housing shortfall has become so entrenched that it’s going to take bigger changes to fundamentally move the needle on the state’s housing market. If Newsom wants to deliver on his pledge he’s going to need to endorse Wiener’s bill or something comparably ambitious.

The basic plan: upzoning near transit and jobs

Wiener’s bill, described by Politico as a plan to “spur housing development near transit, job centers” and the LA Times as a “bill to boost apartment complexes near transit,” does not directly require anyone to build any apartment complexes anywhere.

What it does is prevent cities and towns from banning apartment construction, at least in certain specified areas. Towns would be required to allow apartment buildings in any place that is either:

- within a half-mile of a rail transit station;

- within a quarter-mile of a high-frequency bus stop; or

- within a “job-rich” neighborhood.

In the new special zones, regulatory parking minimums would be sharply reduced and zoning codes would have to allow buildings to be either 45 or 55 feet tall depending on local factors.

The biggest short-term impact of these zoning changes would probably be felt in neighborhoods that are already gentrifying and have a significant amount of housing turnover. Single-family homes that today are sold to flippers or to yuppies looking to undertake a gut renovation project would instead tend to get sold to small-scale apartment developers who would refashion them as denser structures.

The demand for density, however, is highest in rich neighborhoods where the price of land is highest. Units in these neighborhoods turn over more slowly, but the market demand for more housing is essentially infinite so over time it’s easy to imagine whole swathes of single family dwellings in Silicon Valley, Westside Los Angeles, Western San Francisco, etc. being converted to apartments.

One of several political challenges for SB-827 is that public conversation around the bill was dominated by the short-term impact on gentrifying neighborhoods even though the long-term impact on affluent neighborhoods is more important to Wiener’s long-term policy goals. So some of the key changes Wiener has made to the legislation aim to shift that conversation.

How the plan has changed: broader scope, more protections

Reformulated as SB-50, the bill addresses gentrification concerns in two ways.

- It creates an exception to the exception, saying that developers may not use their new apartment-constructing authority to demolish buildings that currently house renters.

- It allows economically vulnerable communities to obtain a five-year delay in implementing the zoning changes.

Under the new plan, low-income neighborhoods won’t see any change at all in the short term. And even over the longer term, today’s California renters won’t see any new financial incentives for landlords to sell to developers.

Instead, new apartments will be built on land that is currently used for owner-occupied housing and for five years that will only happen in richer neighborhoods.

Offsetting those two limitations is an expansion of the up-zoning Wiener has in mind. The original legislation mandated zoning changes in “transit rich” areas, but the new legislation adds the concept of “jobs rich” neighborhoods.

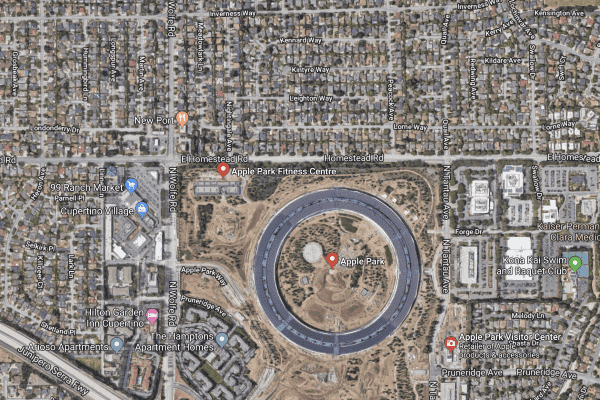

This concept is not precisely defined in the legislation, but the intention is pretty clearly to target suburban jurisdictions that like playing host to corporate office parks (and the property tax revenue they deliver) while excluding any new residents. The sea of single-family homes in Sunnyvale and Cupertino within convenient walking distance of Apple’s corporate campus, for example, seems ripe for some new homebuilding.

This “jobs rich” area happens to be some of the priciest land in America, full of modest-sized single-family detached homes that sell for more than $1.5 million. Replacing such dwellings with mid-rise apartments would be highly profitable and could over time drastically increase California’s supply of homes.

Such moves would not, of course, address the housing needs of the truly disadvantaged — low-income families need subsidies — but market rate building in in-demand areas would greatly reduce the price pressure on older housing stock in poorer neighborhoods, while also increasing the state tax base and making subsidies easier to offer.

Thus modified, SB-50 answers the main official political objection that was leveled against its predecessor, leaving us to see how much of a difference that really makes.

Housing vs. the interests of the privileged

In a liberal state like California, it’s natural for opponents of land reform to couch their objections in the rhetoric of affordable housing, gentrification worries, and anti-displacement. But the reality is that low-income renters’ interests rarely if ever carry the day in politics, as seen in the landslide defeat of a stringent rent control referendum at the ballot box in 2018.

SB-827 failed because anti-gentrification activists joined forces with comfortable homeowners in affluent neighborhoods to kill reform.

Some of the most strident anti-reform rhetoric came from places like Beverly Hills and the rich suburbs of Silicon Valley. After all, exclusionary suburbs didn’t get to be exclusionary because their residents were deeply worried about the possible displacement of working class people of color from poor urban neighborhoods. Their residents want to live in exclusive neighborhoods. That’s why they moved where they moved, that’s why their towns adopted exclusionary zoning codes, and that’s why they opposed changes that would force them to stop.

Wiener’s decisive move to address the gentrification worries while actually expanding the bill’s footprint into more suburban areas is a strong effort to broaden his coalition and cut the opposition off at the pass.

The problem with aligning your policies to squarely cut against the preferences of the powerful and privileged is that they have a lot of power and tend to win political fights. Wiener now has the framing as a progressive reformer that he wants, but that won’t necessarily translate into votes in the legislature.

This is where the governor-elect’s strong-but-vague commitments on the housing issue come into play. He says he wants a drastic increase in the pace of construction to add millions of new units. This is a proposal that would unleash a drastic increase in the pace of construction and add millions of new units. And if the governor is able to get behind something like this proposal and deliver, he’ll have a chance to leave his mark on the state and create a legacy of accomplishment to fuel his national ambitions.

* Correction: An earlier version of this article referred to SB-287 when it should have said SB-827 and was imprecise about the geography of the Apple Park corporate campus.

Sourse: vox.com