On Wednesday, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) and Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) announced a breakthrough budget deal. As Vox’s Tara Golshan explains, the plan will fund the Children’s Health Insurance Program for 10 years and community health centers for two years; increase disaster relief funding for Puerto Rico, Florida, and elsewhere by $80 billion; include $20 billion in infrastructure spending and $6 billion in opioid and mental health treatment; and increase defense spending next year by more than 14 percent relative to existing law.

The deal lasts for two years and costs roughly $300 billion. That’s caused panic among anti-deficit groups and archconservatives worried about growing the national debt. The conservative lobbying group Heritage Action announced its opposition, saying it would treat the deal as a “key vote” and shame Republicans who support it. FreedomWorks, another economic conservative group, called it a “fiscal abomination.”

Robert Greenstein, founder and president of the left-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, comes at the deal from a different perspective. His main priority is protecting and expanding safety net programs for the poor, like food stamps, Medicaid, and the earned income tax credit. But he also takes long-term deficits seriously and views excessively large ones as a threat to the safety net.

I talked to Greenstein on Thursday morning about the deal, what it means for America’s poor and middle class, and if the deficit situation it creates is sustainable. The transcript has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Dylan Matthews

I know we haven’t had much time to evaluate it yet, but what’s your initial takeaway about the deal?

Robert Greenstein

I’m not sure we know everything about the deal, and some details are still emerging. But we’re up on the lion’s share.

As is the case with all deals like this, there are positives and negatives. It’s a compromise in a situation where Republican conservatives control the House, Senate, and White House.

The best thing about the deal is funding coming back into non-defense discretionary spending. I’m worried that some people just hearing headlines will think there is a huge explosion of non-defense discretionary spending. Even with the increases, non-defense discretionary is still 5 percent below the 2010 level after adjusting for inflation, or 11 percent below if you adjust for inflation and population. We’re still well below average historical spending levels as a share of GDP.

The worst aspects of the deal are:

1) As a number of progressives are saying, it doesn’t address the DREAMers, though I think the cards have been on the table for some days that Republicans refuse to address that, and

2) I think it’s very unfortunate that we’re repealing the Independent Payment Advisory Board [IPAB, a board that would reduce Medicare costs by rejecting expensive treatments that aren’t evidence-based], which had the potential to enable cost control. But it’s not fair to blame the deal. Majorities of both parties on Hill want to repeal the IPAB, so it was a question of which vehicle was going to repeal the IPAB. But I think it’s quite unfortunate.

Most of the coverage expansions of the Affordable Care Act are staying, but two of the principal mechanisms for controlling costs, the Cadillac tax and the IPAB — we’re going to end up with neither of those. The parts of the Affordable Care Act that have turned out to be the most vulnerable are the cost-control measures, not the coverage expansions.

Dylan Matthews

Do the increases in defense spending seem reasonable to you? Was that a necessary trade to see spending on non-defense discretionary go up?

Robert Greenstein

That clearly was the cost of the non-defense discretionary spending increase.

One of the fears I also had was that there would be a deal that increased defense and non-defense discretionary spending, but then where would the non-defense discretionary increase go? With Republicans obviously in control of appropriations committees of the House and Senate, and with President Trump, would the increase overwhelmingly go to their priorities and would some areas in great need be shorted?

There’s still a risk of that. But I was surprised and heartened that the deal comes with bipartisan understandings on where a number of the non-defense discretionary increases go. There’s $5.8 billion for the Child Care and Development Block Grant, $20 billion for infrastructure, money for medical research, opioids, etc. I was pleased to see that there was an understanding upfront that in some very important areas, you were going to get non-defense discretionary funding. It wouldn’t have come without the defense increase.

On the defense increase itself, I’m not an expert on the defense budget, and it’s not an area that we have a lot of expertise on at the Center. I don’t have in-depth knowledge of what defense needs. The magnitude of the defense increases, as a layman, does strike me as quite large and likely more than is really needed, but I don’t have the detailed expertise to know that for certain.

Dylan Matthews

The Center, in particular Jacob Leibenluft, has expressed concern about Trump’s infrastructure plans. Trump has, in his budget, proposed cuts to the Highway Trust Fund, Amtrak, the Army Corps of Engineers, the TIGER program, and other infrastructure programs. Leibenluft was also worried that the Trump infrastructure plan’s focus on private sector collaborations would result in funding projects that companies would pay for anyway, and lead to neglect of less profitable projects, like bridge repair or improving public school buildings.

Do you worry about that in the context of the $20 billion in infrastructure spending in this deal? Or do you expect this to go to more conventional and reliable infrastructure programs?

Robert Greenstein

It’s only $10 billion a year for two years for infrastructure. I don’t have any more detailed knowledge. My assumption is that it’s likely to be the current kinds of infrastructure programs we have rather than the programs that Trump has proposed.

We are deeply skeptical of the merits of the Trump plan. My assumption and hope is that this $20 billion is not that. It could be, hopefully, needed infrastructure projects like mass transit and things of that sort. That will get thought out in the appropriations committees over the next few months. It will come to the floor in early or mid-March.

Dylan Matthews

So the bill isn’t giving specifics, it’s just punting most of the decisions to the appropriations committees in the House and Senate?

Robert Greenstein

What this deal does is that it gives the appropriators some markers. Some are very specific. The Child Care and Development Block Grant — that’s a specific program. I’m looking at a document that Schumer’s team put out. It says $20 billion on infrastructure such as wastewater, rural broadband, and energy. How that’s allocated, the details will be worked out in appropriations.

Dylan Matthews

The biggest single cost in the bill, on the non-defense side, is the $60 billion for disaster relief. Is that enough? Is it directed to the right places?

Robert Greenstein

It’s a mixed bag. The area we’ve been following most closely is Puerto Rico. We were pleased to see $5 billion in Medicaid funding for Puerto Rico with no matching requirement. If one had put in $5 billion but said Puerto Rico had to come up with matching funds, the commonwealth can’t do that now. They have no money, and there’s a raging health care crisis going on now in Puerto Rico, due in part to a lack of funding for the Medicaid program.

Puerto Rico is going to need significantly more than what is in this package. I think it’s important that the Puerto Rico provisions are included. I know less about the needs in Florida and Texas, but I assume members, including Republican members, were involved behind the scenes.

Dylan Matthews

What additional support does Puerto Rico need, which the bill doesn’t provide?

Robert Greenstein

Various kinds of investment. I think they need significantly more for rebuilding infrastructure. On health care, they’re going to need more over time. They need significant debt relief, debt forgiveness. The creditors are going to need to take more than a haircut, over a number of years.

But no one expected that in this bill.

Dylan Matthews

The biggest criticism of the bill that I’ve seen is on the deficit. This is another $300 billion added to the national debt, plus a bit more if you include interest payments. And we’re doing it at a time where, while the economy isn’t fully recovered yet, we’re getting close. Unemployment is below 5 percent, and wages are starting to rise a little bit faster. While spending $300 billion with no pay-fors was a very, very good thing to do in 2009 and 2010, it’s a bit different in 2018.

You’ve always been clear that you think long-run deficits are a threat to the safety net. Do you worry about the deal’s deficit impact? Is it fair to oppose it on those grounds?

Robert Greenstein

I largely agree with the things you just said, but I think critics are overstating the role of the deal in the deficit picture.

The nation, in my view, made a significant policy mistake by instituting the sequestration cuts as part of the 2011 Budget Control Act (BCA). They took non-defense discretionary spending down to a level that doesn’t meet national needs and doesn’t fund areas important for national growth, including education, research, and infrastructure. The non-defense discretionary spending increases in this deal still leave you, in real terms or a share of GDP, well below where we were in 2010.

There’s also a lot of funding for disaster relief, which traditionally is not offset. One does not want to deny disaster areas funds while policymakers haggle over offsets. It’s one-time money rather than a permanent part of the budget, and one hopes that 2017 was an unusual year. I do think it would behoove some deficit hawks who were concerned about the level of disaster spending here, if we want to avoid more frequent occurrences of equivalent or even greater levels of disaster spending for decades to come, to get serious about climate change.

Having said that, would I like to have seen a larger share of the package offset? Yes. However, most of the additional appropriate offsets were not acceptable to Republican leaders on the Hill. Clearly they took off the table, from the first second of negotiations, the idea of raising any revenue, closing any loophole, as part of the offsets. They’ve taken off the table savings in programs like Medicare Advantage, or larger savings in drug costs, particularly in Medicare for which there have been a number of credible proposals, many endorsed by MedPAC [the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, an advisory board recommending changes to Medicare to Congress].

My understanding is that Republicans put forward some additional offsets that Democrats rejected, I think appropriately. They were proposals to further unravel parts of the ACA and cause more people to lose health insurance. Those shouldn’t have been acceptable, and weren’t.

The Center’s Paul Van de Water wrote a paper in September looking at the deficit question, and in areas from infrastructure to housing to education and training, we’ve been underinvesting, not overinvesting. This bill is a step in the right direction, though I don’t think it’s close to meeting the unmet needs there. We have an aging population, which Congress can’t pass a law to change. We have accelerating medical costs, which are partly driven by medical innovations. If we have an aging population, expensive medical advances, and we want more investment, we need more revenue!

One of the messages that comes out of this bill is that starve the beast doesn’t work because the public won’t abide many years of underinvestment. At a certain point, we need more revenue, not less. This is a two-year bill; it doesn’t bind levels after two years. The disaster provisions aren’t permanent levels. But if you reduce revenue to 17 percent or below, you’re going to get real problems.

I wish more of it had been offset, but in terms of the fiscal concerns, I think this bill really pales in comparison to the tax cut. My biggest disappointment from a fiscal standpoint is the repeal of the IPAB. But, again, I think the IPAB was dead for some time. This was formally putting the nails in the coffin, but it was never going to be allowed to take effect.

Dylan Matthews

This deal gets us closer to the end of the spending caps imposed as part of the 2011 debt ceiling negotiations. What does the spending picture look like after those go away?

Robert Greenstein

The BCA caps, and the sequestration tied to them, go through fiscal year 2021. This deal covers fiscal year 2018 and fiscal year 2019.

My expectation is that at the end of the Budget Control Act era in 2021, either before it expires or a year or so after, there will be a new law that puts new caps on. I would be very surprised to see a return to the era of no caps. What we found in the 1990s is that caps can work reasonably if you set the caps at a reasonable level, not a wildly unreasonable level no one can live with. If you do that, they get blown away. That’s what happened here. The sequestration caps were devoid of reality on both the defense and non-defense side.

Dylan Matthews

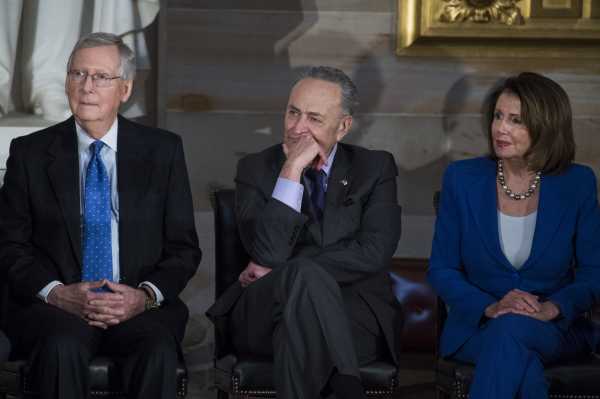

Nancy Pelosi has announced her opposition to this deal, not least because it fails to even ensure a vote on the DREAM Act or other legislation to protect unauthorized immigrants who arrived as children from deportation.

Is that a fair position? Should progressives support this bill?

Robert Greenstein

Immigration aside, I think the merits of the deal really significantly outweigh the demerits. The really hard part is the intersection with the DREAMers, and there are questions there that I don’t know the answers to.

If the deal goes down due to a combination of Democrats voting against and Republicans on the right going against it, the question is: What happens then? Does that lead us to a positive deal on the DREAMers? If there is a government shutdown, what happens then?

When we had a three-day shutdown I was struck by the viciousness with which the White House turned against proposals for DREAMer relief. If the public both supports the DREAMers and opposes the shutdown, does it build more public pressure on behalf of the DREAMers or move public sentiment against them?

I am struck by the fact that historically shutdowns have not succeeded in helping those on the Hill who want something they’re not getting from the president. In 1995-’96, Gingrich lost and Clinton won. The thing that is also striking me is that all Pelosi was asking was for Ryan to agree to what McConnell agreed to weeks ago, to at least have a debate and vote. It’s stunning that Ryan isn’t willing to agree to that.

There’s Republican control of the House, Senate, and White House, Ryan says he won’t do anything Trump doesn’t want, and Trump seemingly continues to act like an adolescent on these issues. He’s the one who started this by withdrawing DACA protection. Then he said he wanted to solve it, and said what he wanted. Sens. Durbin [D-IL] and Graham [R-SC] came up with a plan that did that, and he rejected that. He rejects every deal coming out of the Hill.

With the current lineup of forces, what is the strategy that would work with the DREAMers? It isn’t clear to me that there’s a strategy that Democrats and pro-DREAMer Republicans on the Hill could take that would make Ryan move. I hope that’s wrong. It’s possible that the only move here is through the ballot box in November. But I really expected movement on a bipartisan front well before this, and they just keep blocking it.

I think there are some who are rightly upset and outraged. There’s a search: If only Democrats adhere to strategy X, they will back down. The only strategy that will force a move is even stronger mobilization of public opinion across the country on behalf of the DREAMers and in opposition to the president’s stance. It’s not clear to me what’s the strategy that would work. I’m not sure what it is. That’s part of what makes this so difficult.

Dylan Matthews

How much of the problem is the “Hastert Rule” — the convention that bills that a majority of the House supports, but only a minority of Republicans support, can’t come to the floor for a vote?

Robert Greenstein

It clearly causes Ryan more problems in the House. But it’s possible you could get a majority of House Republicans for a reasonable compromise. Even if you couldn’t, it would be easier for Ryan to breach the Hastert Rule if Trump were supporting a plan.

At the end of the day, the core of the problem is the president. Elections have consequences. Obama used his executive authority for good, to help the DREAMers, and Trump is using it in the opposite way.

Sourse: vox.com