We know the US economy is bad right now. Millions of people have lost their jobs, and millions more will. Estimates for how much unemployment is expected to spike and GDP will fall are staggering. Production and spending across much of the country have been brought to an abrupt halt.

It’s natural to want to see a light at the end of the tunnel, obviously in terms of the health crisis caused by coronavirus but also for the economy. And there will be one — eventually.

“The very best case scenario is we rapidly bounce back and we get close to something where we were before. Personally, I think that’s highly unlikely. The shock from the virus is going to trigger a broader economy-wide recession,” said Jesse Edgerton, an economist at JPMorgan. “That’s a really harsh reality.”

Related

Coronavirus could lead to the highest unemployment levels since the Great Depression

The question of when and how the economy gets better largely hinges on our ability to get the virus itself under control. Despite calls from some Republican lawmakers to get back to business before that happens and even some speculation about reopening the economy early from the president, it’s not a realistic scenario — people aren’t going to be falling over themselves to go out to restaurants and pack into movie theaters as a deadly virus spreads, or as they or their loved ones get sick.

At some point — and we don’t know exactly when — the economy will bounce back, at least partially. When it does, that new normal will be different. Many Americans may be worse off than they were before, some people may still be afraid to resume their lives as they once lived them, and many businesses may have permanently closed.

“There will likely be some permanent damage inflicted on the economy,” says Greg Daco, chief US economist at Oxford Economics. “What this shock is doing is exacerbating preexisting inequality issues across the country. The individuals who have been hit the hardest are the individuals who were in the most precarious position to start with.”

Economists say it could be anywhere from 2021 to 2031 before the economy returns to something like the pre-coronavirus “normal.” But it will never be entirely the same.

“We’ve never seen anything like this before, so we’re speculating along with everyone else,” Edgerton said.

What the economic recovery will look like: contraction, a partial bounceback, and the long slog

The first prerequisite for economic recovery will be a public health solution: widespread testing, tracing of possible infections, antibody testing for immunity, adequate supplies for the health care system, and so on. The coronavirus outbreak will need to be firmly under control before the economy can resume anything approaching normalcy, and we just don’t know yet when the public health breakthrough will happen. Consumers need confidence participating in the economy won’t get them or their loved ones sick before they will revert to their typical economic activity.

Related

Social distancing can’t last forever. Here’s what should come next.

“The longer these issues linger in the form of people not having confidence in returning to their daily activities,” Daco said, “the more severe these dislocations will be.”

But once that has been achieved, the problems and solutions we are dealing with will become more recognizably economic. Jason Furman, a former top economist for President Barack Obama who is now at Harvard, told Vox the economic fallout and recovery will likely have three stages:

The timeline for the second and third steps is difficult to know. The recovery is likely to look robust at first; Furman suggested we could see some of the most impressive job gains (one million or more in a month) and GDP growth numbers ever. Parts of the economy should be able to snap back to something approximating their pre-crisis state.

And such a quick recovery could be self-reinforcing, at least up to a point.

“If the economy starts surging back then some businesses will suddenly face insufficient capacity. Those businesses will have to double-down on hiring, ordering supplies and investment in new equipment, capital, etc.,” Karl Smith, vice president of federal tax and economic policy at the Tax Foundation, says. “That then provides an extra boost of demand for the rest of the economy that produces a secondary wave of investment.”

While it’s impossible to rule out a rapid and complete return to normalcy — a V-shaped recovery, in the economists’ lingo — most experts we spoke to consider it unlikely. Too much structural damage has been done, jobs and businesses lost that will never come back. Supply chains have been broken and need to be rebuilt.

Americans are more likely to find themselves in something like the 2011 or 2012 environment after the Great Recession: The economy is no longer the biggest story in the world, but the unemployment rate will be high and wages will still be depressed. It’s helpful to remember how the economic recovery began last time around in June 2009, when the national unemployment rate was at 9.5 percent. A year later in 2010, it was stuck at 9.4 percent. In 2011, it was 8.2 percent. Unemployment didn’t fall below 5 percent until early 2016. And in this crisis, the unemployment rate is expected to have an even higher peak.

“The shock from the virus there is going to be enough to tip off at least a normal recession in the rest of the economy beyond these direct effects of the sectors that we have had to shut down. … We should expect the next nine months or a year to look like a recession, to continue to see high levels of unemployment and depressed levels of output,” Edgerton said. He predicted that “it will be at least a few years before we feel as good as we did in January.”

How long this lasts, and what the recovery looks like, depends on actions while the health crisis is still underway. The government has passed a $2.2 trillion stimulus package to try to prop up the economy in the meantime, and more federal spending will be needed. But transitioning from stimulus provisions to a normal economy can be tricky.

Smith pointed out the enhanced unemployment aid will be a boon to consumer demand in the short term while depressing labor supply, but as soon as it’s cut off, demand could drop because people have less money to spend and not everyone will get a new job immediately. (One way to avoid that: a phase-out of some kind.)

“It really depends, to my mind, on just how much damage is done during the time that the economy is shut down in the way it is now,” said former Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen in a recent interview with CNBC. The more workers are laid off, the more households that run down their savings, the more people who fall behind on their bills, the longer the slog of recovery.

The recovery can take many shapes if you think of it as a line graph: a V, a U or, worst of all, an L (sharp sudden drop and long gradual climb). Yellen said, “The more damage of that sort is done, the more likely we are to see a U, and there are worse letters, too, like L, and I hope we don’t see something like that.”

Inequality could get worse because low-wage workers getting hit the hardest

Just as we saw after prior economic crises, not everybody will experience the same recovery. For the wealthy and higher-income people, those who didn’t lose their jobs and whose financial well-being was more marginally affected, they may bounce back to normal quickly once they go back to work full-time and the stock market starts to improve.

“There will be some individuals who have V-shaped recovery,” Claudia Sahm, who worked a the Federal Reserve through the 2008 recession and is now director of macroeconomic policy at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, says. “The people who came into this with a good financial position… they’re gonna be fine.”

But the job market for low-wage workers is probably going to look a lot worse, even as the broader economy starts to pull out of the coronavirus recession.

At the beginning of this year, the unemployment rate was down around 3 percent and wages were ticking up. That’s basic supply-and-demand: there weren’t a lot of workers out there looking for a job, so firms had to raise wages to be competitive. But that new reality, which took years to reach after the Great Recession, has been completely dismantled.

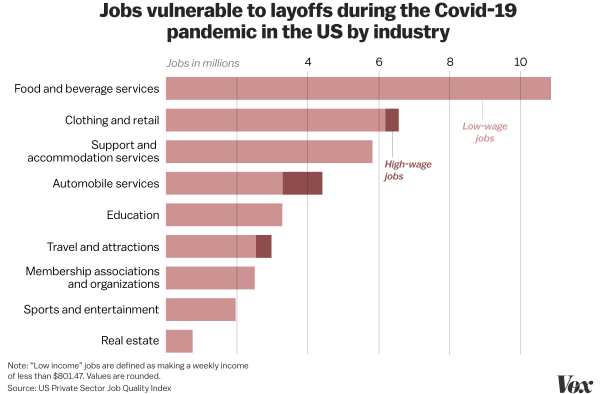

We already know that low-wage service sector jobs were the most vulnerable to being cut because of the Covid-19 pandemic.

And when the public health crisis is over and life starts to return to normal, unemployment could be 15 or even 20 percent. There are going to be a lot of workers looking to fill those open slots, especially as the emergency unemployment benefits in the stimulus bill start to expire.

“Wages are going to come out of the recovery worse than they were,” Sahm says. “Everything is going to be worse for workers who went into the recession in the most fragile position and there are a lot of them.”

The horizon for workers may shake out differently depending on geography. University of California Berkeley economist Danny Yagan found that after the Great Recession, workers who lived in places that were hard hit by the recession were less likely to be employed at all in 2015, even if the local unemployment rate had recovered. It appears that years later, some people in the most affected areas had just given up looking for work altogether.

The economic crisis may exacerbate racial income inequality as well. In 2015, a report from the ACLU estimated that by 2031, wealth for white households would be 31 percent less than it would have been had the Great Recession never happened. For black households, it would be down nearly 40 percent. And the coronavirus crisis is already hitting black communities especially hard. Early numbers suggest black people are at higher risk for contracting and dying from coronavirus, and a smaller proportion of black and Hispanic workers are able to work from home compared to Asian Americans and whites.

“We know that blacks, Latinx, and native people, in terms of race and ethnicity, they have lower levels of reserves, and we also know that their employment is more precarious than that of white people,” Darrick Hamilton, the executive director of the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at Ohio State University, recently told Vox.

Some parts of the economy will never be the same

Maybe the hardest truth to accept, however, is that some things will never go back to the way they were.

The travel and hospitality industries could be in for a long depression of their own, depending on how quickly people are to trust the safety of international travel or venturing far from their own homes. This is where the public health response comes back into play: the sooner people feel confident about testing and infection tracing, confident enough to book a flight and a hotel room in some far-flung destination, the sooner those industries will be back to normal.

“Where I do see the potential for change, and I don’t know if it’s permanent or long-lasting, is travel,” Daco says. “There may be an environment of caution going forward in terms of travel. You’ll likely see a normalization in local services first, before you see a normalization in travel-related activity. People are still going to be cautious when it comes to boarding a plane and going on a vacation. The same may be true for business travel.”

The same goes for bars and restaurants, at least in the short term — it might be some time before people are comfortable crowding into such establishments, and many may not survive the crisis at all. As much as you may be trying to order delivery to keep your local favorites afloat, you cannot order enough pad thais to pay their rent. But, presumably, at some point, people will start going out to eat again like they once did.

It may take some time for live events to enjoy the audiences they once did, too, though Furman said he expects that at some point, the live entertainment industry will look pretty much the same as it did before the crisis.

And broadly speaking, we may see greater market concentration in sectors where many small businesses were lost. Congress has tried to prop up small businesses through loans approved in the stimulus package, but there are already reports of problems with the actual administration of those benefits. The more small businesses that close because of either the initial economic shock or a problem accessing federal benefits, or both, the more the markets they leave behind will be concentrated in a handful of dominant players.

It’s certainly worth asking if Americans want the economy to go back exactly to the same way it was. The coronavirus crisis has exposed and exacerbated deep flaws in the US system, including the economy. Corporations that just got a massive tax cut may now not have many resources to weather the downturn. Why were large businesses able to spend much of that tax windfall on stock buybacks and executive compensation? Why haven’t workers been paid enough to build up savings to get by when they lose their jobs by not fault of their own? Where is the social safety net?

“In the United States, economic inequality has been on the steep incline for a long time, and there were many people already on the verge before this happened, systems already failing,” said Jamila Michener, an assistant professor of government at Cornell University. “It just highlights all the cracks and the flaws and faults that already existed.”

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Sourse: vox.com