From a policy standpoint, the single most important thing about former Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort’s sentencing on Wednesday in federal court is an observation from his lawyers: He never even would have ended up charged under normal circumstances.

If Manafort had not gotten caught up in special counsel Robert Mueller’s Russia investigation, his lawyers argued to two different judges, he’d never have been arrested or charged for his myriad white-collar crimes.

From a legal standpoint, the argument “and I would have gotten away with it, too, if it weren’t for you meddling special counsels” isn’t especially strong.

Judge Amy Berman in Washington, DC, rejected it and seemed to suggest that it was a play for sympathy from the president or the media rather than legally relevant to the court.

However, it seemed compelling to Judge T.S. Ellis in Virginia, who imposed a very lenient sentence on Manafort.

Even if Berman is correct (which she is), the argument does happen to be true. Manafort got up in Mueller’s dragnet, and Mueller’s motive for prosecuting the case was an effort to secure cooperation from Manafort. Manafort backed out of his agreement, which is why he ended up back in court facing a potentially harsh sentence.

If Trump had lost the 2016 election, he never would have been in a position to fire FBI Director James Comey in 2017, no special prosecutor would have been appointed, and Manafort’s various tax evasions and other frauds would have gone undetected.

But the problem isn’t the federal government punishing Manafort, it’s how rarely the perpetrators of Manafort-style crimes get punished at all.

White-collar sentencing is relatively lenient

The extent to which Manafort’s prison sentence seems light compared to the harsh justice the United States routinely hands down to drug offenders and violent criminals was immediately striking to progressives.

This disparity, however, naturally raises the difficult question of whether white-collar sentences are too short or other sentences are too long.

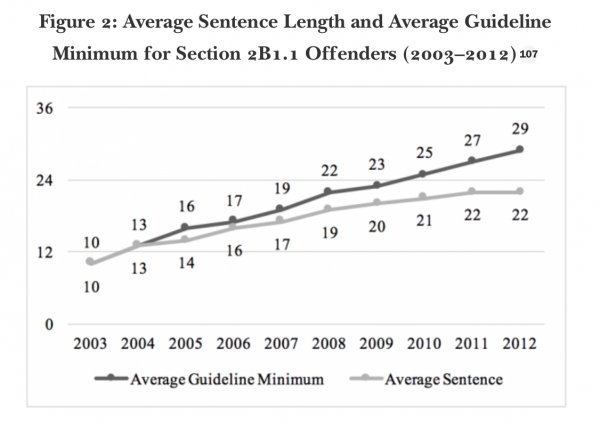

Research by Mark Bennett, Justin Levinson, and Koichi Hioki shows that the leniency Manafort received is fairly typical for white-collar defendants. Judges routinely depart from sentencing guidelines in these cases, almost always to impose a sentence that is lower than what is recommended by the guidelines.

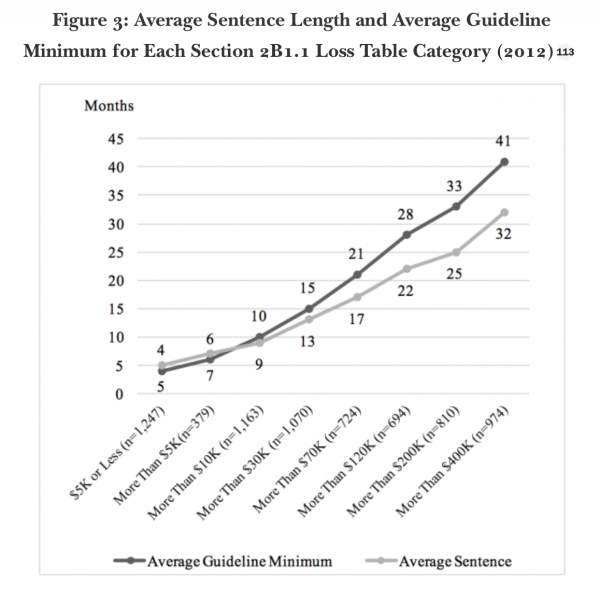

This is especially true for white-collar cases that involve larger amounts of money. Bigger frauds do attract longer sentences, but in practice, judges raise the punishment level by less than the guidelines recommend.

Over time, the scale of the frauds that actually make it to court has gotten bigger, so there is a growing wedge between the recommended sentences and the ones that actually get imposed — even though sentence length has grown over time.

Tellingly, the authors of the study find that Democrat-appointed judges and Republican-appointed judges are equally likely to hand out merciful sentences in white-collar cases, even though Democrat-appointed judges are much more likely to give merciful answers to philosophical questions like “people who commit serious crimes sometimes deserve leniency.”

In other words, the Ellis-Manafort situation where a GOP-appointed judge not normally given to merciful sentencing happens to find a fellow affluent white professional to be more sympathetic than the normal criminal defendant appears to repeat itself across the system.

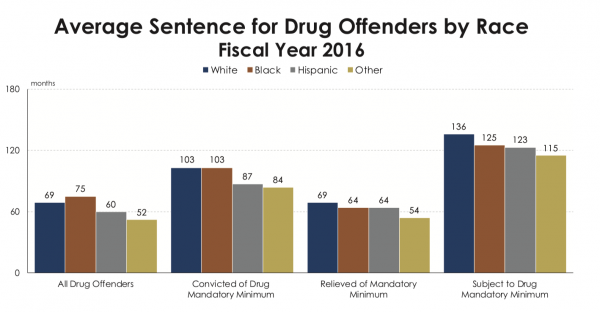

Drug offenders serve, according to US Sentencing Commission data, much more time on average that fraud offenders.

Criminal justice reformers annoyed by this disparity typically argue that it shows we need not tougher sentences in white-collar cases but rather more lenient sentences in other cases. As Shaila Dewan and Alan Blinder put it, “every defendant should be treated like a rich white man.”

But that only underscores the need to invest more in detecting and catching these crimes in the first place.

Detection is more important than punishment

The mass incarceration era of American criminal justice was inspired, at least on an intellectual level, largely by the thinking embodied in Gary Becker’s famous 1968 paper “Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach.”

Becker argued for treating criminals as rational actors, who weighed the benefits of crime against the cost — with the cost understood as the odds of detection versus the severity of punishment once caught. Logistically speaking, increasing sentence length was easier than figuring out ways to get better at solving crimes. What’s more, increasing severity also spoke to public interest in retribution. Consequently, the United States invested massively in increasing the severity of punishment without doing much to increase the odds that criminals would get caught.

Decades of experience have shown us this didn’t work out at all.

As fellow economist Alex Tabarrok put it in a retroactive assessment of Becker’s work on crime, “longer sentences didn’t reduce crime as much as expected because criminals aren’t good at thinking about the future; criminal types have problems forecasting and they have difficulty regulating their emotions and controlling their impulses.”

What does seem to work is taking steps to actually make it harder to get away with crime. Putting more police officers on the street has a large and consistent tendency to reduce crime, whereas locking away criminals for longer and longer sentences is mostly cruel and expensive.

That said, if the Becker-style rational agent approach were to work anywhere, it would be with sophisticated white-collar crimes. These are precisely the type of offenders who are most likely to be good at making long-range plans and doing elaborate cost-benefit reactions. Precisely because the typical perpetrator of a massive tax evasion or complicated fraud is someone the typical judge can recognize and empathize with, harsh punishment is more likely to work.

But attempting to brainwash judges into turning off their empathy is unlikely to work, and deliberately cultivating a culture of non-empathy is a generically bad idea. Congress actually tried in the past to force judges to impose harsher sentences in white-collar cases, but the Supreme Court has ruled this unconstitutional. The reformers’ view that we should try to spread the circle of empathy wider is much more appealing than the concept of making it more restrictive.

Yet that only underscores exactly how damaging it is to make it easy to get away with these crimes undetected. If sophisticated criminals know they are likely to be treated mercifully in court if caught, it is very important for them to think that they are fairly likely to be caught. The fact that a quality legal team can argue in open court — and be believed — that the only reason their extremely guilty client was detected is that he stumbled into a loosely related political scandal is a huge problem with the American system.

But Congress has elected to spend more than twice as much money on the two federal law enforcement agencies charged with stopping illegal immigrants, Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Customs and Border Protection, as they spend on the FBI. That’s even though the FBI’s mission includes counterterrorism and counterintelligence, organized crime, and a range of other responsibilities.

Obviously, it is well-understood that despite their fairly lavish budgets, ICE and CBP have not, in practice, succeeded in creating a situation where all unauthorized immigrants are caught, detained, and removed. That state of affairs is frequently portrayed as a kind of urgent national crisis requiring even harsher crackdowns, even more money, and all the rest.

Under the circumstances, it’s naturally the case that given the drastically smaller pool of resources dedicated to white-collar crime — especially in light of the greater complexity of the cases — a lot of crooks end up slipping through the cracks. Elevated interest in the criminality of Trump and his inner circle is, to an extent, changing that.

But if the Trump era ever comes to an end, America should consider taking a hard look at a more systemic change. After all, the very fact that we’ve found ourselves in this situation is a reminder that the Trump crew is but one symptom of a much larger illness.

Sourse: vox.com