On Friday, the Supreme Court announced that it will hear a lawsuit challenging the leadership structure of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB).

This announcement came after the Trump administration essentially threw in the towel in this challenge to the consumer protection agency started by senator and presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren. As a general rule, the Justice Department has a duty to defend federal laws challenged in court. The administration, however, decided not to defend the law at issue in this case.

The policy implications of this suit, Seila Law v. CFPB, are unclear. In the narrowest sense, Seila Law is a case about whether a federal agency can be led by a single director that the president cannot remove at will. More broadly, however, the case is the most recent skirmish in a war over what kind of government our Constitution permits.

Most likely, the Supreme Court will hold that the president may remove the CFPB director. In the short term, that could give a big boost to a future Democratic president — potentially allowing a President Warren to replace Trump’s CFPB director with her own on the first day of her presidency.

But the Court could also go much further. There is a chance — albeit a very small one — that the Supreme Court could strike down the CFPB in its entirety. There’s a somewhat greater chance that the Supreme Court could disallow “independent” agencies in which the leaders of those agencies are protected against removal by the president.

President Trump, in other words, could gain the power to fire members of the Federal Reserve board who refuse to inject steroids into the economy while Trump is running for reelection.

Looming over all of this is an ideological battle over the “unitary executive,” the theory that all executive power in the United States government must be vested in the president, and over the legacy of the late Justice Antonin Scalia.

The fight over who can fire the CFPB director

Most federal agencies are led by a Cabinet secretary or some other senior official who can be fired by the president. By contrast, independent agencies such as the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) or the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) are often led by bipartisan boards whose members serve staggered terms. Often, the members of such boards can only be fired by the president “for cause,” which typically prevents a president from removing a board member simply because they disagree with that board member’s policy views.

The CFPB is unusual. It is led by a single director, not by a board. But that director also is protected from a president who wants to fire them. By law, the president may only remove the CFPB Director “for inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office.”

This unusual arrangement enrages many conservatives. Indeed, one particularly conservative federal judge claimed that “consent of the governed is a sham” if the CFPB’s structure is allowed to stand.

To understand why this case inspires such intense feelings, turn back the clock about three decades to the Supreme Court’s 1988 decision in Morrison v. Olson. Morrison involved a federal law, which expired in 1999, that provided for “independent counsels” — a form of special prosecutor that could only be fired by the president for cause.

The Supreme Court upheld the independent prosecutor statute by a lopsided 7 to 1 vote, with Justice Antonin Scalia providing the sole dissenting vote.

The thrust of Scalia’s opinion: The Constitution provides that “the executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States.” For Scalia, “this does not mean some of the executive power, but all of the executive power.” And because the power to bring prosecutions is invested in the executive branch of government, there cannot be a prosecutor who is neither answerable to the president or answerable to some lower official who is answerable to the president.

This is the theory of the unitary executive. The executive branch has a single org chart. And the president must be above everyone else in that chart.

Scalia’s dissent is quite broad. It does not simply attack the independent counsel statute. It also mocks the Court’s 1935 opinion in Humphrey’s Executor v. United States, which permitted the creation of independent agencies led by multimember boards.

If a majority of the Court embraced the full implications of Scalia’s dissent, the president could potentially gain the power to fire FCC Commissioners or destroy the independence of the Federal Reserve.

At the very least, however, the CFPB’s structure — with a single director who can’t be removed by the president — is anathema to proponents of the unitary executive. Like the statute at issue in Morrison, the statute challenged in Seila Law vests the kind of power traditionally held by the Executive Branch in a single person. Indeed, it does even more than that, giving that single individual command over an entire federal agency.

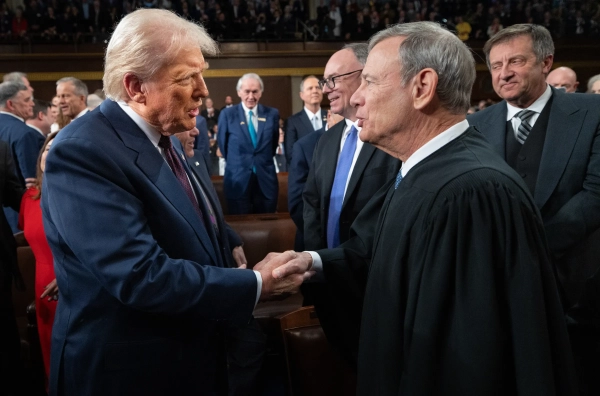

Many powerful conservatives now revere Scalia’s dissenting opinion the same reverence commonly associated with a religious text. One of them is Justice Brett Kavanaugh, who said in 2016 that he wanted to “put the final nail” in the Morrison majority opinion’s coffin.

How far is the Supreme Court likely to go?

A handful of judges have claimed that the entire CFPB must be eliminated because of this alleged constitutional defect in leadership structure. That’s unlikely to happen. As a lower court judge, Kavanaugh heard a very similar lawsuit that presented the same question of whether the CFPB could have a single director who cannot easily be fired by the president. Though Kavanaugh agreed that the director must be accountable to the president, he wrote that the CFPB may continue to operate with the president able “to remove the Director at will at any time.”

And without Kavanaugh’s vote, it’s hard to see how litigants who want the CFPB to die can find five votes on this Supreme Court.

At least in the short term, a decision embracing Kavanaugh’s view could potentially be a boon to Democrats, as it would allow a Democratic president to replace the CFPB director on the first day of their presidency. Kavanaugh’s position, which the Trump administration shares, would effectively transform the CFPB into an ordinary agency whose leadership changes whenever partisan control of the White House flips.

A more uncertain question is whether there are five votes to go “full Scalia,” and potentially eliminate independent agencies led by multimember boards.

Thus far, the Roberts Court has taken incremental steps towards a unitary executive, but it’s largely left Humphrey’s Executor in place. In its 2010 decision in Free Enterprise Fund v. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, for example, the Supreme Court struck down a scheme that gave members of a particular government board “double for-cause” protection.

Members of the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board could be removed by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), but only “for good cause shown.” Meanwhile, the SEC commissioners themselves could only be removed by the president for “inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office.” This double layer of insulation from the president was one layer too much for a majority of the Supreme Court.

Yet Roberts’s majority opinion in Free Enterprise Fund was careful not to go much further than that. “The point is not to take issue with for-cause limitations in general,” he wrote, emphasizing that “we do not do that.”

But the Supreme Court is now significantly more conservative than it was in 2010, and it is an open question whether Roberts will be willing to consider a broader holding in Seila Law. If he is, Trump could suddenly become much more powerful.

Sourse: vox.com