Two facts were evident at Wednesday morning’s Supreme Court hearing in Louisiana v. Callais, a legal challenge prompting the Court to eliminate enduring protections against legislative maps drawn to disadvantage racial groups.

Firstly, the Court will divide along partisan lines, with all six Republicans intending to abolish the federal Voting Rights Act’s (VRA) limitations on racial gerrymandering, and all three Democrats dissenting. Secondly, the Republicans lack unity concerning the manner in which they should author an opinion nullifying these safeguards.

SCOTUS, Explained

Obtain the most recent updates on the US Supreme Court from senior correspondent Ian Millhiser.

Email (required)Sign UpBy submitting your email, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Notice. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Although all six Republican justices almost certainly entered Wednesday’s hearing with a specific outcome in mind, they possessed considerably differing theories regarding the means to achieve it.

Justice Samuel Alito seemed to contend that maps excluding Black voters are acceptable as long as they were put in place to favor the Republican Party, instead of being rooted in explicitly white supremacist motives.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh asserted that the Voting Rights Act should expire after an unspecified period.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett suggested placing a restriction on Congress’s authority to address discrimination — one that the Court has utilized in cases unrelated to voting — on laws connected to elections, like the VRA.

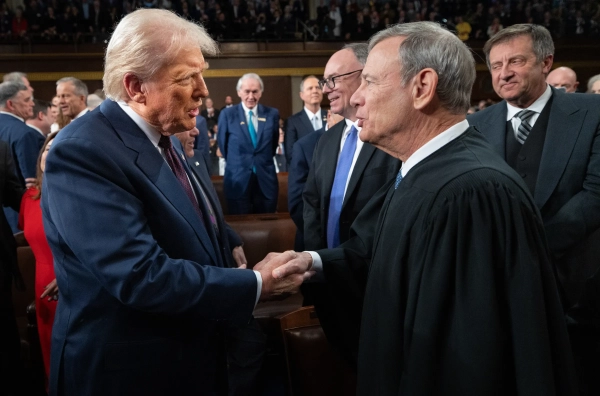

However, even if the Court’s Republican majority cannot reach a consensus on a justification for ending decades-old protections against racial gerrymanders, their desire to eliminate them has been clear for some time. As a junior attorney, Chief Justice John Roberts played a key role in a failed endeavor to persuade President Ronald Reagan to reject an amendment to the Voting Rights Act that strengthened its protections and initiated its current regulations against gerrymandering.

Related

- The uneasy dilemma with America’s most significant civil rights law

Despite Roberts surprising numerous Court observers when, in a 2023 case nearly identical to Callais, he authored an opinion that maintained the VRA’s anti-gerrymandering stipulations. Roberts stated on Wednesday that the 2023 case “considered the existing precedent as a given.” In Callais, conversely, the Court specifically requested that the parties address whether requiring states to create maps that offer increased representation to racial minorities, as the VRA occasionally mandates, violates the Constitution.

In essence, the Court asked the lawyers opposing Louisiana’s existing maps to directly dispute the precedents which, Roberts now claims, he previously “considered as a given.”

Furthermore, the Republican justices initiated the process of dismantling the Voting Rights Act a decade ago, in Shelby County v. Holder (2013), and they’ve rendered at least two additional verdicts since then that assailed this significant civil rights law. Therefore, in the highly probable scenario that Callais further diminishes the VRA, it will represent a continuation of an ongoing Republican objective.

Wednesday’s hearing was primarily political theater. The result of this case was almost undoubtedly decided well before the hearing commenced.

How we got here

The Voting Rights Act, as revised by the law Reagan signed in 1982, prohibits any state election rule that “results in a denial or curtailment of the right of any US citizen to vote due to race or ethnicity.” In Thornburg v. Gingles (1986), the Court determined that this wording requires states to revise their legislative maps under specific circumstances.

While the Gingles framework is intricate, it largely relies on two elements: whether a state experiences residential segregation by race, and whether the state’s voters exhibit racial polarization — implying that voters of one race typically vote for one party, while voters of another race typically vote for a different party.

When these two elements are present, they generate two distinct political groups within a state. And the racial group in the majority can exploit its control over the state legislature to draw electoral district maps that exclude the other racial group from representation. Gingles ruled that courts must sometimes intervene when this transpires and mandate new maps that grant increased representation to the minority groups.

In Callais, as an example, Louisiana’s Republican legislature initially created maps that contained only one (out of six) Black-majority congressional districts, in spite of the fact that Black individuals comprise approximately 30 percent of the state’s population. A lower court, employing Gingles, overturned this map, and the state responded by creating new maps featuring a second Black district.

During Wednesday’s hearings, the Court’s Republicans presented a disorganized array of criticisms of this Gingles framework. Alito, for instance, seemed to disagree with Gingles’s premise that racially polarized voting is a problem. Louisiana, he argued, implemented its maps to safeguard Republicans, not to exclude Black individuals from representation. And partisan gerrymandering, as Alito has stated previously, is permissible.

Justice Neil Gorsuch, meanwhile, seemed to desire imposing a double bind on racial gerrymandering plaintiffs that the Court recently rejected in the 2023 case.

The Gingles framework necessitates these plaintiffs to generate a sample map demonstrating the feasibility of drawing additional districts where a racial minority group constitutes the majority, because if drawing such a map is not feasible, then pursuing litigation regarding whether the state must draw one is pointless. However, Gorsuch seemed to argue that it is unconstitutional for courts to consider these sample maps, given that the sole means of creating one involves drawing lines based on race.

Kavanaugh, meanwhile, proposed broadening a rule that the Court announced in Shelby County. In that case, the Court concluded that a central provision of the Voting Rights Act — requiring states with a history of racist election laws to secure “preclearance” from the federal government for new election laws — could no longer remain effective because the United States displayed less racism in 2013 than it did when the VRA was initially enacted in 1965.

Numerous of Kavanaugh’s queries implied that a comparable rule must extend to the VRA’s racial gerrymandering protections, and that those protections should also expire after a certain period.

Lastly, Barrett suggested that the Voting Rights Act might contravene a standard, recognized as “congruence and proportionality,” that the Court initially announced in City of Boerne v. Flores (1997). City of Boerne addressed the extent of Congress’s authority to enforce civil rights safeguards enshrined in the 14th Amendment. Nevertheless, the Voting Rights Act was enacted under Congress’s authority to enforce the 15th Amendment, which forbids states from denying the right to vote “on account of race, ethnicity, or previous condition of servitude.”

The Supreme Court has never applied City of Boerne to a 15th Amendment case. And, regardless, it is unclear how Congress, which amended the VRA in 1982, could have adhered to a test that the Court first announced in 1997.

Regardless of which argument the Court’s Republican supermajority opts to embrace, there were no surprises during Wednesday’s hearing. The Court’s Republicans suggested various, highly divergent justifications for their desire to overturn the VRA’s racial gerrymandering protections, yet they were all moving in the same direction. It’s difficult to envision Callais concluding favorably for voting rights plaintiffs.

Source: vox.com