At any given time, for the past several weeks, more than 2,000 children have been held in the custody of US Border Patrol without their parents. Legally, they’re not supposed to be held by border agents for more than 72 hours before being sent to the Department of Health and Human Services, which is responsible for finding their nearest relative in the US to house them while their immigration cases are adjudicated.

In practice, they’re being held for days, sometimes weeks, in facilities without enough food or toothbrushes — going days without showering, overcrowded and undercared for.

Late last week, the conditions of that detention in one facility in Clint, Texas, became public when investigators, checking on the US government’s obligations under the Flores agreement (which governs the care of immigrant children in US custody), were so horrified by what they saw that they turned into public whistleblowers.

The stories they told have horrified much of America. The past several days have seen growing outrage, and the acting commissioner of Customs and Border Protection (which oversees CBP) announced his resignation Tuesday (though officials maintain the outrage didn’t cause the resignation).

But the problem goes beyond one official — or one facility.

The story gained even wider traction after Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s (D-NY) reference to the detention facilities as “concentration camps,” and the ensuing debate over whether that term was appropriate.

The US government’s response was to move the children out of the Clint facility — and move another group of children in.

On Monday, officials confirmed that all 350 of the children there last week would be moved to other facilities by Tuesday; about 250 of them have been placed with HHS, and the remainder are being sent to other Border Patrol facilities. But on Tuesday morning, a Customs and Border Protection official told a New York Times reporter on a press call that about a hundred children were currently being housed at Clint.

That’s illustrative of the hectic improvisation that’s characterized much of the Trump administration’s response to the current border influx. It’s a problem that is much, much bigger than the problems at a single facility. Indeed, the problems investigators identified at Clint are problems elsewhere as well.

The lone member of the team of legal investigators who visited the El Paso facility in which many children were sent from Clint — called “Border Patrol Station 1” — told Vox that conditions there were just as bad as they were in Clint, with the same problems of insufficient food, no toothbrushes, and aggressive guards.

The problem isn’t the Clint facility. The problem is the hastily-cobbled-together system of facilities Customs and Border Protection (the agency which runs Border Patrol) has thrown together in the last several months, as the unprecedented number of families and children coming into the US without papers has overwhelmed a system designed to swiftly deport single adults.

It is apparent that even an administration acting with the best interests of children in mind at every turn would be scrambling right now. But policymakers are split on how much of the current crisis is simply a resource problem — one Congress could help by sending more resources — and how much is deliberate mistreatment or neglect from an administration that doesn’t deserve any more money or trust.

Related

The border is in crisis. Here’s how it got this bad.

Border Patrol isn’t prepared to care for children at all. It’s now housing 2,000 a day.

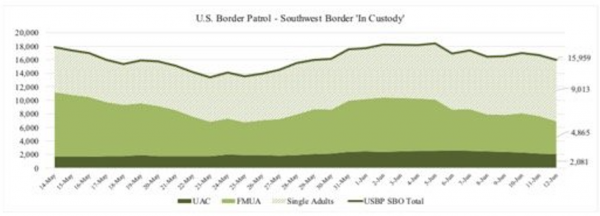

According to statistics sent to congressional staff last week and obtained by Vox, between May 14 and June 13, US Border Patrol facilities were housing over 14,000 people a day — and sometimes as many as 18,000. (The most recent tally, as of June 13, was nearly 16,000.)

Most of these were single adults, or parents with children. But consistently, over that month, around 2,000 — 2,081 as of June 13 — were “unaccompanied alien children,” or children being held without adult relatives in separate facilities.

In an early June press call, a Customs and Border Protection official said, referring to the total number of people in custody, “when we have 4,000 in custody, we consider that high. 6,000 is a crisis.”

Traditionally, an “unaccompanied alien child” refers to a child who comes to the US without a parent or guardian. Increasingly — as lawyers have been reporting, and as the investigators who interviewed children in detention last week confirmed — children are coming to the US with a relative who is not their parent, and being separated.

Because the law defines an “unaccompanied” child as someone without a parent or legal guardian here, border agents don’t have the ability to keep a child with a grandparent, aunt or uncle, or even a sibling who’s over 18, though advocates have also raised concerns that border agents are separating relatives even when there is evidence of legal guardianship.

Under the terms of US law — and especially the 1997 Flores settlement, which governs the treatment of children in immigration custody — immigration agents are obligated to get unaccompanied children out of immigration detention as quickly as possible, and to keep them in the least restrictive conditions possible while they’re there. Barring emergencies, children aren’t supposed to be in Border Patrol custody for more than 72 hours before being sent to HHS — which is responsible for finding and vetting a sponsor to house the child (usually their closest relative in the United States).

That hasn’t been happening. Attorneys, doctors, and human rights observers have consistently reported that children are being held by Border Patrol for days or longer before being picked up by HHS. And in the meantime, they’re being kept in facilities that weren’t built to hold even adults for that period of time, or in improvised “soft-sided” facilities that look like (and are commonly referred to as) tents.

The detention conditions crisis doesn’t just affect children. But conditions for children are under special legal scrutiny.

Since late last year, US immigration agents have been overwhelmed by the number of families coming across the border. The US immigration system, which was built to quickly arrest and deport single Mexican adults crossing into the US to work, doesn’t have the capacity to deal with tens of thousands of families (mostly from Central America) who are often seeking asylum in the US.

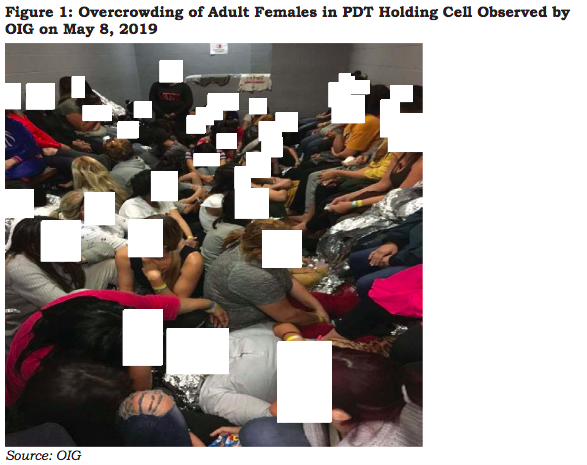

The length of time migrants are spending in Border Patrol custody (and the conditions there) have attracted some alarm before. In April, pictures of migrants being held outside under a bridge in El Paso, fenced in and sleeping on the ground, attracted outrage and led Border Patrol to stop holding migrants there. And in May, the DHS Office of the Inspector General released an emergency report about dangerous overcrowding of adults in two facilities: with up to 900 people being held in a facility designed to hold 125.

Because of the Flores settlement, lawyers have the opportunity to investigate conditions for children to see if the government is complying — and possibly ask a judge to intervene if it is not. That’s what spurred the fact-finding mission that led to last week’s stories.

The reports about Clint broke at a time when the Trump administration was already playing defense about its compliance with the Flores settlement. (While the administration is working on a regulation that would supersede the terms of the agreement, that regulation isn’t expected to be published in final form until fall, and may well be held up in court.)

In a 9th Circuit Court of Appeals hearing earlier last week about whether the administration needed to allow a court appointee to monitor conditions for children in ICE and CBP custody, Department of Justice lawyer Sarah Fabian told judges that children didn’t necessarily need towels or toothbrushes to be in “safe and sanitary” conditions — a clip that looked especially bad when the Clint stories came out showing the children were being denied just that.

The court hearing was not specifically about the Clint facility — it wasn’t about what investigators found last week at all. And as Ken White explained for the Atlantic, Fabian’s cringeworthy “safe and sanitary” argument came from the awkward stance the Trump administration has taken in this litigation: In order to challenge the court appointment of a special monitor, they argued that there’s a difference between a promise to keep kids in “safe and sanitary” conditions (which the government has agreed to for decades) and a guarantee of particular items like toothbrushes.

The court appeared unimpressed. And the stories about Clint and other facilities that have come out in the ensuing days certainly bolstered the case that the Trump administration has either willingly violated its agreement to keep kids safe and healthy, or has been unable to keep it — or a mix of both.

The problem isn’t Clint

The problems that investigators identified at Clint — too many people, not enough food, no toothbrushes — weren’t inherent to that facility. They were indications of an overloaded (or neglected) system.

And it’s already clear that those problems go beyond Clint.

ABC News obtained testimony from a doctor who visited another facility for children in Texas — the Ursula facility — and witnessed “extreme cold temperatures, lights on 24 hours a day, no adequate access to medical care, basic sanitation, water, or adequate food.” She said the conditions were so bad that they were “tantamount to intentionally causing the spread of disease.”

The children are now being sent from Clint to a facility that is just as bad, according to Clara Long of Human Rights Watch, who was the only member of last week’s investigative team who visited it.

Long told Vox that when she was there, the facility in El Paso known as “Border Patrol Station 1” was mostly being used as a transit center where migrants were staying only a few hours before going elsewhere. But she spoke to one family who had been held in a cell there for six days, and who voiced the same concerns that children in the Clint facility did.

The mother of the family, Long said, was so ashamed of not having clean teeth — the El Paso facility, like Clint, wasn’t providing enough toothbrushes — that “when she was talking to you she would put her hand up in front of her mouth and wouldn’t take it down.” The teenage son said he was afraid of the guards because when he’d gotten up to go to the bathroom in the middle of the night, a guard had shoved him back into his cell and slammed the door on him. For two nights, the family had had to sleep on the cold floor without blankets.

The fundamental question: Why is it taking so long to get kids out of custody — and is it happening on purpose?

Most of the children who were at Clint when the team visited last week — about 250 of the 350 — were set to be sent to HHS custody by Tuesday.

Questions remain about what is happening to the other 1,750 or so children who were in Border Patrol detention on Thursday if levels have remained static since mid-June, and why the government was able to place only 250 children over five days with the agency that’s supposed to take responsibility for all children within 72 hours.

It’s not clear where the bureaucratic breakdown really is — and whether it’s the result of resource constraints or choices about how resources are used.

The Trump administration definitely has made a choice to keep single adults in detention, even if it could release them. Border Patrol chief Carla Provost has told Congress that “if we lose (the ability to keep and deport) single adults, we lose the border.” That does raise questions about whether the overcrowding in adult facilities could be avoided.

But it doesn’t address the issue of unaccompanied children, who can’t simply be released with a notice to appear in immigration court. While children with parents in the US could theoretically be placed with those parents, the government is supposed to vet potential sponsors to make sure it’s not placing children with traffickers — but that’s the job of HHS, and the vetting doesn’t begin until children are released from Border Patrol custody.

Observers and policymakers agree that HHS simply doesn’t have the capacity to take migrant kids in. One Democratic Hill staffer compared it to a “jigsaw puzzle”: Not only are there only so many spaces available to place a child, but the facilities available might not match the child’s particular needs. (You can’t put an infant in an HHS shelter for teens, for example.) But another Hill staffer told Vox that HHS claims it’s never refused a transfer for space reasons, muddying the waters.

Then there’s the question of whether CBP is really doing all it can to care for kids in the time they’re in CBP’s care.

One of the Clint observers told Isaac Chotiner of the New Yorker stories of cruelty from some guards, indicating that they were deliberately punishing children for the sin of coming to the US without papers. But she also said that many guards were sympathetic, and told the observers that children shouldn’t be in their custody — implying that they were doing the best they could and simply didn’t have the resources to do more. (Advocates also say they’ve tried to donate supplies to Border Patrol facilities but had their donations rejected; it’s not clear if this was a Border Patrol decision, or if there’s a legal complication banning outside donations.)

Congress is considering a package right now to give the Trump administration billions more dollars to deal with migrants coming into the US. To Democratic leadership, including the appropriators led by Rep. Lucille Roybal-Allard (D-CA), who drafted the House version of the supplemental package, the solution to poor conditions in custody is to provide more money specifically to improve those conditions. They emphasize that the bulk of the funding will go to HHS to increase capacity for migrant kids and that funding for ICE and CBP will be strictly limited to humanitarian use.

But to some progressives, led in Congress by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, giving any money to immigration enforcement agencies right now is an endorsement of the current state of affairs.

The not-one-more-dime camp, in part, is taking a bright-line stance against the detention of children. But in part, they’re demonstrating a lack of trust in the administration to adhere to any law or condition. And they assume that any money given to ICE for transit of migrant kids will, in some way or another, encourage ICE to detain more families and arrest more immigrants in the United States.

The “smart money” camp, on the other hand, believes firmly that without funds to improve conditions in detention, the conditions will only get worse.

That’s especially relevant in the case of kids deemed “unaccompanied,” who have to remain in custody until a sponsor is found. The past few days have demonstrated that those children are extremely vulnerable and that much of the American public wants their situation to change. It just may not be clear how.

Sourse: vox.com