It is impossible to talk about the causes of America’s opioid epidemic without pointing to the manufacturers and distributors that marketed and proliferated dangerous opioid painkillers. Yet for much of the crisis, these multibillion-dollar opioid companies have avoided much in the way of serious accountability.

Until, perhaps, now.

Last week, New York City made headlines for its announcement that it had filed a lawsuit against opioid manufacturers and distributors. But New York City is actually joining late on a bipartisan movement that really took off in 2017, as cities, states, and other jurisdictions filed lawsuits against opioid companies. At this point, there are up to hundreds of such lawsuits in play, with more to come.

The lawsuits have built to a point where a federal judge in Cleveland has now convened talks between governments around the country and drug companies to try to come up with a settlement that all parties can agree to.

There are two major legal arguments behind these cases, one against opioid manufacturers and another mainly against opioid distributors:

1) Starting in the mid-1990s, opioid manufacturers unleashed a misleading marketing push underplaying the risks of opioid painkillers and exaggerating the drugs’ benefits. This, the lawsuits argue, adds up to false advertising with deadly consequences — by encouraging doctors to overprescribe the pills and getting patients to think the pills were safe and effective.

2) Meanwhile, opioid distributors supplied a ton of these pills, even when they should have known they were going to people who were misusing the drugs. This is backed by data that shows that in some counties and states, there were more prescribed bottles of painkillers than there were people — a sign that something was going very wrong. Federal and some state laws require distributors to keep an eye on the supply chain to ensure their products aren’t falling into the wrong hands. Letting these drugs proliferate, the lawsuits say, violates those laws.

Opioid manufacturers and distributors, of course, ferociously deny these allegations. While some suits have been settled, and some executives have even been criminally convicted for their involvement in the epidemic in the past, opioid companies vigorously reject the argument that they have carelessly fueled the current drug crisis. And so far, what the companies have paid by and large amounts to peanuts compared with the profits they’ve taken in from the drugs.

Nearly 64,000 people died of drug overdoses in 2016, and at least two-thirds of those deaths were linked to opioids. While these deaths are increasingly linked to illicit opioids like heroin and fentanyl, the rise in opioid misuse, addiction, and overdose originally began with the proliferation of prescription painkillers — which were overprescribed by doctors, allowing the drugs to flow not just to patients but to friends and family of patients, teens rummaging through parents’ medicine cabinets, and the black market. (For more on the causes of the crisis, read Vox’s explainer.)

According to the lawsuits, opioid companies enabled this epidemic. With the talks in Cleveland, the hope is the legal challenges will eventually lead to a big settlement — one that would quash the practices that helped lead to the deadliest drug overdose crisis in American history and help address the consequences of the crisis.

The case against opioid makers: false advertising

The big argument against opioid makers: These companies knew — or should have known — that their products weren’t safe or effective, yet they advertised their products as safe and effective anyway.

One lawsuit representative of this line of argument is Ohio’s, which goes after Purdue Pharma, Endo, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries (and subsidiary Cephalon), Johnson & Johnson (and subsidiary Janssen Pharmaceuticals), and Allergan.

The lawsuit cites several examples of misleading marketing: An Endo-sponsored website, PainKnowledge.com, in 2009 claimed that “[p]eople who take opioids as prescribed usually do not become addicted.” Janssen approved and distributed a patient education guide in 2009 that attempted to counter the “myth” that opioids are addictive, claiming that “[m]any studies show that opioids are rarely addictive when used properly for the management of chronic pain.” Purdue sponsored a publication from the American Pain Foundation, which was heavily funded by opioid companies, claiming that the risk of addiction is less than 1 percent among children prescribed opioids — suggesting pain is undertreated and opioids are necessary.

This is only a small sampling. In total, Ohio Attorney General Mike DeWine claims opioid companies spent “millions of dollars on promotional activities and materials that falsely deny or trivialize the risks of opioids while overstating the benefits of using them for chronic pain.” In doing this, he argues that opioid makers are “borrowing a page from Big Tobacco’s playbook.”

Contrary to opioid companies’ claims, there has been evidence for literally centuries that opioids are highly addictive. Some of their marketing, in fact, explicitly tried to debunk this well-known fact: They characterized the understanding that opioids are addictive and potentially deadly as “opiophobia.” They latched onto a five-sentence letter to a medical journal that, with no real proof, claimed addiction among opioid patients is rare. (One author of the letter later said he was “mortified” at what drug makers had done.) And they directly communicated with doctors — through videos, pamphlets, and other marketing — to foster the idea that new opioids on the market were safe and effective.

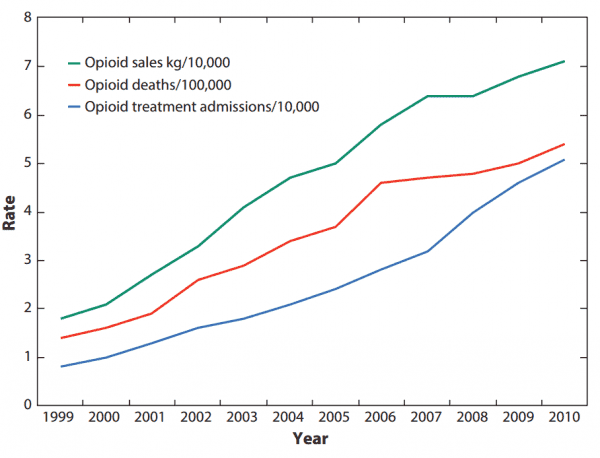

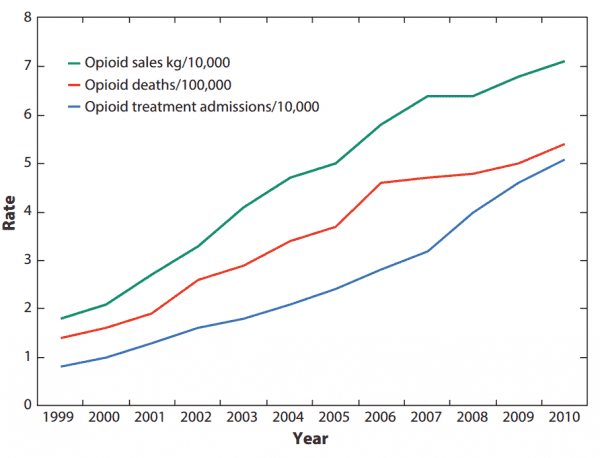

The current epidemic is proof of what we already knew: As opioid companies saw their profits increase, so too did drug overdose deaths and addiction treatment admissions.

It’s not just the addiction claims, though. Opioid companies also misled doctors and the public about the effectiveness of their specific drugs.

As an extensive Los Angeles Times investigation found, Purdue’s opioid OxyContin was marketed for its supposed ability to provide 12 hours of pain relief. But as Harriet Ryan, Lisa Girion, and Scott Glover reported, “Even before OxyContin went on the market, clinical trials showed many patients weren’t getting 12 hours of relief. Since the drug’s debut in 1996, the company has been confronted with additional evidence, including complaints from doctors, reports from its own sales reps and independent research.”

This was critical to Purdue’s competitive advantage: If it really didn’t provide 12-hour relief, then it wasn’t more effective than other similar painkillers on the market. In the face of the evidence, though, Purdue stood by its claim for years. And it told doctors that if patients weren’t seeing the promised results, then the problem was that doses were too low.

These efforts, it seems, were in the name of profit. One sales memo uncovered by the Times was literally titled “$$$$$$$$$$$$$ It’s Bonus Time in the Neighborhood!”

This is alarming for public health: As the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) warned, higher doses significantly increase the risk of overdose and addiction.

The Los Angeles Times investigation found, “More than half of long-term OxyContin users are on doses that public health officials consider dangerously high, according to an analysis of nationwide prescription data conducted for The Times.”

Opioid makers’ claims that their drugs are an effective treatment for chronic pain are similarly faulty. There’s simply no good scientific evidence that opioid painkillers can effectively treat long-term chronic pain as patients grow tolerant of opioids’ effects — but there’s plenty of evidence that prolonged use can result in very bad complications, including a higher risk of addiction, overdose, and death. In short, the risks outweigh the benefits for most chronic pain patients.

Yet opioid makers were highly influential in perpetuating the claim that their drugs can treat chronic pain. Several public health experts explained the recent history of opioid marketing in the Annual Review of Public Health, detailing Purdue Pharma’s involvement after it put OxyContin on the market in the mid-1990s:

By encouraging long-term prescriptions for chronic pain, opioid companies fueled the epidemic. As a CDC study found, the risk of dependency, which can lead to addiction, dramatically increases the longer one uses opioids.

This is the kind of marketing that led Ohio to file a lawsuit. Similar challenges from Mississippi, Oklahoma, Missouri, New Hampshire, and other states are going through the courts right now. Local jurisdictions in several states have also filed similar challenges. Kentucky previously settled with Purdue (for $24 million) and Janssen (for nearly $16 million) in cases alleging misleading marketing.

In 2007, Purdue Pharma and three of its top executives paid more than $630 million in federal fines for their misleading marketing. The three executives were also criminally convicted, each sentenced to three years of probation and 400 hours of community service.

As the opioid epidemic has continued, however, more and more lawsuits are expected to come.

I reached out to the companies named in Ohio’s lawsuit. Only Purdue gave a comment on the record: “We share the attorney general’s concerns about the opioid crisis and we are committed to working collaboratively to find solutions. OxyContin accounts for less than 2% of the opioid analgesic prescription market nationally, but we are an industry leader in the development of abuse-deterrent technology, advocating for the use of prescription drug monitoring programs and supporting access to Naloxone — all important components for combating the opioid crisis.”

The case against opioid distributors: allowing diversion

Beyond the false advertising charges, there’s a separate legal argument, dubbed the “diversion theory” by some proponents, for companies that distribute, as opposed to manufacture, opioids.

Under federal and some state laws, opioid distributors have a legal obligation to stop controlled substances from going to illicit purposes and misuse. The diversion theory argues that these distributors clearly did not do that: As the opioid epidemic spiraled out of control, and as some counties and states had more prescriptions than people, it should have become perfectly clear that something was going wrong — yet, the claim goes, distributors continued to let the drugs proliferate.

Michael Canty, an attorney at the New York–based firm Labaton Sucharow who’s advising states and other jurisdictions on opioid-related legal challenges, drew a comparison between opioid distributors and credit card companies.

“[Credit card companies say], ‘Someone tried to make a very large purchase on your account in another state and we flagged it as suspicious and stopped it from going through.’ That’s what distributors should be doing,” Canty previously told me. “For example, there’s a small town with 500 residents, and the local pharmacies order a million pills from the distributors. That should set off an alarm bell from a compliance standpoint or a quality control standpoint, where the distributors say, ‘Wait a minute, what’s going on here? We need to investigate this order. And until it passes muster, we won’t ship.’”

The Cherokee Nation’s lawsuit is representative of this line of argument, leveled against big names like the McKesson Corporation, Cardinal Health, AmerisourceBergen, CVS, Walgreens, and Walmart. The lawsuit has some fairly alarming numbers behind its claim: 845 million milligrams of opioids were distributed in the 14 counties that make up the Cherokee Nation — which, if you assume an average pill size of 20 milligrams, amounts to 360 pills for each prescription opioid user in the Cherokee Nation.

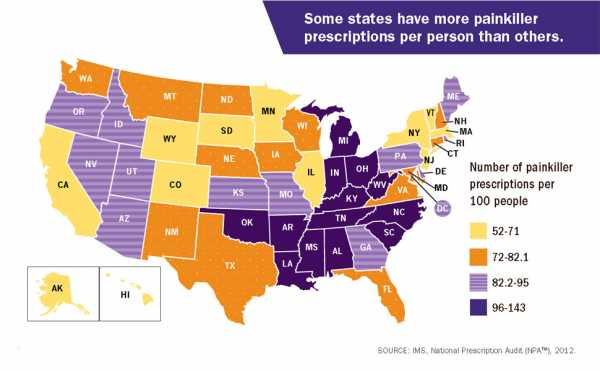

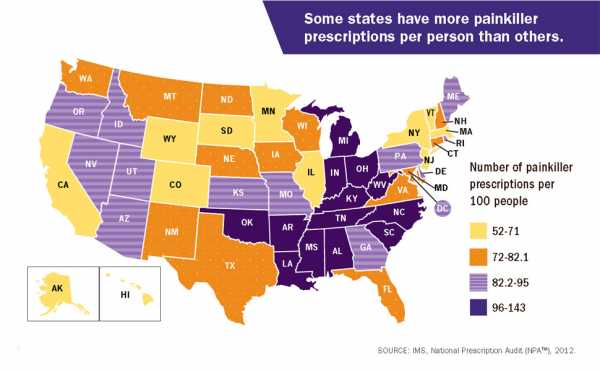

This is part of a national problem. The CDC, for example, put out 2012 data that found there were more painkiller prescriptions than people in several states.

West Virginia’s case is particularly striking. It is the state hardest hit by the epidemic, suffering the highest rate of overdose deaths in 2016. A previous investigation by the Charleston Gazette-Mail in West Virginia found that from 2007 to 2012, drug firms poured a total of 780 million painkillers into the state — which has a total population of about 1.8 million. Some of the numbers were even more absurd at the local level: The small town of Kermit has a population of 392, but a single pharmacy there received 9 million hydrocodone pills over two years from out-of-state drug companies.

“When you have 140 prescriptions being written for every 100 people, you know that people have failed to meet their obligations,” Serena Hallowell, who’s also with Labaton Sucharow, previously told me. “And they’re not just ethical obligations, which I would say they have too. They’re obligations under state and federal law and their own industry guidelines as well.”

The Cherokee Nation’s lawsuit was the first to go after all the big opioid distributors at once, but other jurisdictions have pursued legal challenges as well. West Virginia, for one, settled with Cardinal Health and AmerisourceBergen for $36 million in payouts (although the companies denied wrongdoing). Several other jurisdictions are now pursuing similar challenges.

Meanwhile, some distributors have already been dealt penalties for their negligence. In 2017, for example, McKesson agreed to pay a $150 million settlement to the Department of Justice for failing to report suspicious orders of pharmaceutical drugs, particularly opioids, and stopped sales at some distribution centers in multiple states. And that came after McKesson paid a more than $13 million fine for similar violations in 2008.

CVS, Walgreens, and Cardinal Health have also paid fines, sometimes multiple times, for similar violations in the past several years.

Similar challenges could, in theory, be tried against opioid manufacturers as well. The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), for one, previously pursued one of the nation’s largest opioid makers, Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, for the proliferation of its pills in Florida since 1999. But as the Washington Post found, the investigations went nowhere. In the end, the company agreed to pay, without admitting wrongdoing, just $35 million to settle the case with the federal government — far from the billions in dollars the DEA reportedly hoped for, and a tiny fraction of the $3.4 billion in revenue the company reported in fiscal year 2016.

I contacted the opioid distributors named in the Cherokee Nation’s suit for comment. AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, and CVS said they are committed to stopping the misuse of their products, and that they will work closely with federal regulators to do so. Cardinal Health went further, arguing that it “is confident that the facts and the law are on our side, and we intend to vigorously defend ourselves against the plaintiff’s mischaracterization of those facts and misunderstanding of the law.”

A big goal of the lawsuits: a tobacco-style settlement agreement

Despite the fines and settlements, policymakers and advocates aren’t satisfied with what opioid companies have paid so far. Hundreds of millions of dollars is obviously a lot of money for most people. But for companies that make billions of dollars a year, it’s not much.

Take Purdue Pharma. In 2007, it paid a penalty more than $630 million. But thanks to OxyContin, the company has reaped more than $31 billion in revenue since the mid-1990s. The 2007 fine adds up to just 2 percent of what the company has made in revenue, which isn’t much of a deterrent for Purdue. Indeed, Ohio’s lawsuit alleges that Purdue continued its misleading marketing after 2007 — citing, as one example, a 2011 pamphlet in which Purdue argued that signs of addiction are actually a form of “pseudoaddiction” that suggests someone needs more, not fewer, opioid painkillers to treat pain.

The crisis also likely demands far higher damages than a few hundred million dollars. A 2016 study, for instance, estimated the total economic burden of prescription opioid overdose, misuse, and addiction at $78.5 billion in 2013, about a third of which is due to higher health care and addiction treatment costs. Many jurisdictions can’t afford to pay for these new expenses — and may need a big legal settlement or legal damages to do so, especially as the federal government lags in its response to the opioid crisis.

Richard Fields, an attorney with the Cherokee Nation case, put the cost for his clients in the hundreds of millions of dollars. “That’s an extraordinary sum for a sovereign nation of 350,000 people,” he previously told me. “The suit is [in part] an effort to recover for what we think is a very direct harm caused by these companies.”

“But,” he added, “the hope is too that if enough attorneys general around the country bring these suits, they can do what the [federal government] hasn’t been able to do on its own.”

In the long term, one hope for the different lawsuits is that they’ll eventually snowball, leading to an outcome similar to what happened with tobacco companies in the ’90s. That’s what may be happening now in the Cleveland talks.

In 1998, big tobacco companies agreed to the Master Settlement Agreement with 46 states. This massive agreement forced tobacco companies to pay tens of billions in upfront and then annual payments, and it put major restrictions on the sale and marketing of tobacco products.

Similarly, a big settlement with drug companies could place restrictions on marketing for opioids. Money from the lawsuits could also help pay for addiction treatment. The latter would help fill a major gap in care: According to a 2016 report from the surgeon general, only 10 percent of people with a drug use disorder get specialty treatment — in large part due to a lack of access and options in their area.

There are parallels between tobacco and opioid companies: Both knew they were selling a dangerous product, yet they misled the public about it — leading people to get addicted and die. (And now that opioid companies are facing pressure at home, they are borrowing a page from big tobacco companies and taking their product internationally with the exact same kind of messaging they used before, with claims that opioids are good for chronic pain and not very addictive.)

But there are some major differences that could make it much harder to get a tobacco-style settlement for opioids. The big one is that, unlike cigarettes at the time of the Master Settlement Agreement, opioids are already regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This could let opioid companies punt responsibility to the FDA, since the agency approved these drugs for medical use. Jodi Avergun, a former chief of staff at the DEA and now a defense lawyer, told Reuters that this is a “fundamental weakness” of the current lawsuits.

There are other issues, like the involvement of the rest of the health care system in the opioid crisis, from medical boards to doctors to patients themselves. That all of this involved so many different actors could insulate opioid companies from carrying too much of the legal consequences. That’s especially true since some of these other actors have copped to serious negligence; the West Virginia Board of Pharmacy, for one, admitted that it didn’t enforce a law for reporting suspicious orders of narcotics for years.

“With tobacco, it really is an interaction between an industry and the consumer,” Keith Humphreys, a drug policy expert at Stanford University, previously told me. “In this case, there was supposed to be this intervening body that also failed. That doesn’t mean the pharmaceutical companies should get off, but … plenty of other people enabled it.”

Still, the lawsuits keep on coming. “Both Democrat and Republican attorneys general have expressed an interest in this,” Canty said. “They are serious about the epidemic. They are educated on the epidemic. They understand the magnitude of the problem and want to be proactive in addressing it.”

Sourse: vox.com