One year into Donald Trump’s presidency, as he delivered his first State of the Union address, he has more or less abandoned his outspoken pledges to bring down the cost of America’s medicines, the highest in the world.

“Despite continuing rhetoric that the pharmaceutical companies are getting away with murder,” said Rachel Sachs, a Washington University in St. Louis professor who follows drug pricing, “he has done absolutely nothing on this issue, and that has actually surprised me.”

Trump was unorthodox about drug prices during the 2016 campaign. He swore to stand up to the pharmaceutical companies, long revered as among Washington’s powerful interests. He told Time, in his Person of the Year interview in December 2016: “I’m going to bring down drug prices. I don’t like what has happened with drug prices.”

Under Trump, drug companies have undertaken a concerted campaign to shift the discussion about drug prices to a conversation about out-of-pocket costs, in which health insurers and pharmacy benefits managers are under the microscope.

The companies’ campaign appears to have borne fruit, judging by regulatory changes being pursued by the Trump administration on Medicare. Trump has also filled the executive branch with officials closely tied to the drug industry; his new pick to lead Health and Human Services, Alex Azar, was most recently a top executive at Eli Lilly.

As Azar was sworn into office Monday, Trump promised again that he would bring prescription drug prices “way down.” In his first State of the Union address the next night, he again pledged that he would bring down drug costs.

“One of my greatest priorities is to reduce the price of prescription drugs. In many other countries, these drugs cost far less than what we pay in the United States,” Trump said in his speech. “That is why I have directed my Administration to make fixing the injustice of high drug prices one of our top priorities. Prices will come down.”

But experts say that in first year of Trump’s presidency the drug industry has gained the upper hand in the lobbying campaign against its foes in the health care industry.

“I think they think they had a good year. They dodged a bullet,” Len Nichols, a health policy professor at George Mason University, told me. “I think of the pharmaceutical pricing issue as somewhat of a titanic struggle between pharma and the plans. If you think of it that way, in the Trump administration, pharma won Round 1.”

Trump promised repeatedly during the campaign he would bring down drug prices

Trump was in many ways unlike any candidate — particularly any Republican — who came before him. Exhibit A: his promise to bring down drug prices. Back in January 2016, he was arguing that Medicare should be directly negotiating the prices it pays for medications and blaming the lobbying power of the drug companies for preventing it.

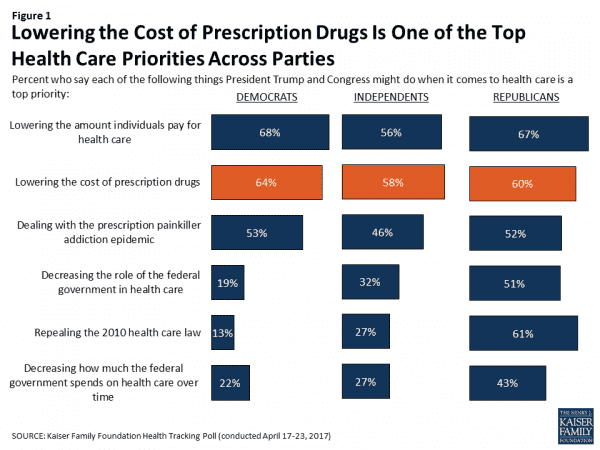

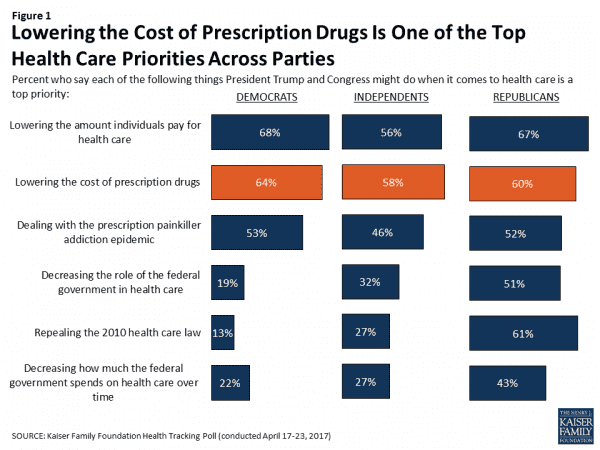

It was a position far closer to that of Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT), an avowed democratic socialist, than a more conventional Republican like Florida Sen. Marco Rubio. But Trump was on firm populist ground. Fresh off the outrage over “pharma bro” Martin Shkreli, alleged price-gouging by the company Valeant Pharmaceuticals, and groundbreaking but costly hepatitis C drugs, the public had named drug prices as their No. 1 priority for American health care in late 2015.

That furor hasn’t faded much in the intervening months. Last spring, the Kaiser Family Foundation again found drug costs right near the top of the public’s priorities.

Trump viscerally tapped into that anger, and he stuck with the issue throughout the 2016 campaign. Advocating for a big-government approach to lowering drug costs put him at odds with the Republican Party but in line with what Americans say they want.

He wasn’t afraid to use the most vivid rhetoric at his disposal to describe the ills of the pharmaceutical industry.

“They’re getting away with murder,” Trump told reporters in January 2017, picking up on the exact language Sanders had used during the Democratic primary. “Pharma has a lot of lobbies and a lot of lobbyists and a lot of power.”

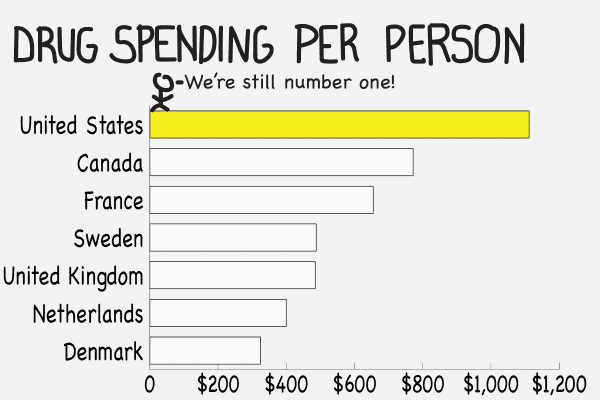

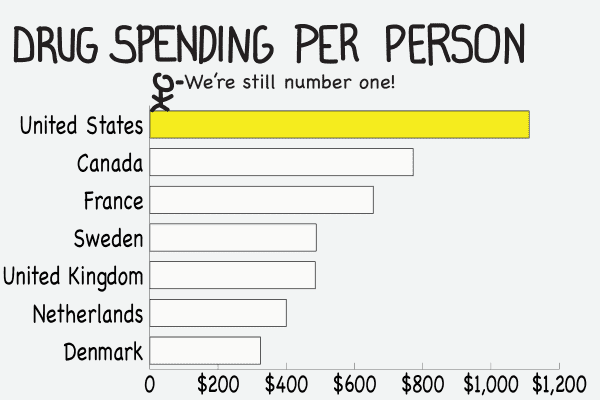

Candidate Trump was onto something very real: Americans do spend more per person on drugs than any other country in the world. As health insurance plans shift to higher out-of-pocket costs for their customers, people feel more and more of that burden.

Hopes were high among the advocates working to lower drug prices. The industry was skittish. The stage was set for a showdown.

Drug prices haven’t been a priority for Trump’s White House

But a big fight over drug prices never materialized. Instead, the Trump administration has been successfully courted in many ways by the pharmaceutical industry.

The industry was already launching its bold counteroffensive in the pricing debate: Three days after Trump was sworn into office, the trade association PhRMA announced a new advertising campaign to rebrand drug makers as leaders in medical innovation.

The campaign would have happened no matter who was in the White House, and PhRMA’s new president, Steve Ubl, has marshaled a new strategy at the group, seeking to more directly engage in the debate, industry officials say. The industry association took steps to rid itself of some bad actors too. There was, to some extent, a legitimate response to the shifting public discourse about drug prices.

But there was no guaranteeing what kind of audience pharma would find in President Trump, given what he had said before he took office. During his first month in office, several top pharma executives met with the new president at the White House.

Coming out of that meeting, Trump was using language that sounded much more familiar — and much more comfortable — to drug companies. He was talking about increasing competition and lightening the regulatory burden to get drugs approved.

“There has been an education of Mr. Trump,” one top industry insider told me. “To where the real costs are, to the impact of other players in the system, and to the cost benefits of medicine in the system.”

“It was important,” this person said of the White House meeting. “The CEOs showed respect to the president. They came, they sat around the table, they were chastened by his comments. … It began a pathway of sincere dialogue. ‘Okay, you wanna talk? Let’s talk.’”

(Another sign of the times: When Trump rubbed shoulders with the global elite in Davos, Switzerland, last week, two top drug executives got a seat at the White House’s private dinner.)

Trump’s campaign pledge to have Medicare directly negotiate drug prices never seriously resurfaced after that meeting. A promised executive order on drug prices never materialized; Politico reported in June that a list of the possible policy changes that had been pulled together “include[d] policies that read like gifts to the drug industry.”

Trump selected an industry-favored nominee to lead the Food and Drug Administration, Scott Gottlieb. After his first health secretary was forced to step down amid a scandal over charter jet travel, the president turned to Azar, who oversaw drug pricing at Eli Lilly for years, to lead the agency.

While Gottlieb has earned praise for the work he has done at the FDA to increase competition, and Azar will enter HHS having pledged to do more on drug prices, they are nonetheless far afield from Trump’s campaign rhetoric. They have never signed on to the policies that Trump pushed as a candidate.

Azar took a far more nuanced tone than his boss in his Senate confirmation hearing, noting that private Medicare Part D plans already do negotiate prices themselves, while cracking open the door — but hardly rushing through it — for tweaking other parts of Medicare to address drug costs.

“When populism meets reality, reality usually wins,” Kim Monk, who tracks health policy for investors at Capital Alpha, told me. “The folks he’s brought in tend to be free market folks, industry folks who don’t like the government negotiating drug prices because they don’t believe it would work.”

The discussion about drug “prices” isn’t about prices anymore

Trump’s promises coming into office were unambiguous: He wanted to bring down drug prices, and he planned to confront the pharmaceutical industry directly. But a year later, the discussion about drug prices has shifted to something else.

The spotlight has been turned on health plans, for structuring benefits so that customers are paying more out of pocket for medications. Scrutiny is also on pharmacy benefits managers, the mysterious third parties that often oversee drug transactions and take a cut of the profits for themselves.

The Washington Post’s Carolyn Y. Johnson meticulously documented how the drug industry has successfully put its industry adversaries under the microscope in the price debate. It’s been a campaign with millions of dollars and hundreds of hours of lobbying manpower behind it.

The drug industry is happy to take the credit for the paradigm shift, arguing that the campaign has had resonance because it highlights a real problem — the byzantine infrastructure that helps inflates drug costs.

“We have been part of an education effort to broaden the bull’s-eye,” the industry insider told me. “I want people to know as much as possible about where their health care dollars go.”

That’s a net win for drug companies. “I think pharma is very happy to have the policy debate turn to the distribution chain,” Monk said.

The Trump administration’s agenda has reflected this new orientation. HHS has proposed changes to Medicare that would cut down on practices used by health plans disparaged by pharmaceutical companies. Those practices include not counting assistance that drugmakers provide to their customers toward the out-of-pocket maximum that Americans with private Medicare Part D plans are required to pay.

The administration is also reviewing changes to another federal program that gives certain hospitals a mandated discount on drug prices, which drug companies have long said is exploited by hospitals without benefiting patients.

At the FDA, Gottlieb has been praised by all sides for the steps his agency has taken to encourage more generic competition: The agency approved 1,000 generics in 2017. But that is an area where drugmakers have said they are willing to compromise — because they prefer to make it easier for cheaper generic drugs to come to the market than to have more direct government intervention.

“Scott is quite sincere and doing what he can on the generic competition,” Nichols said, adding: “That’s pretty much nice little window dressing around the edges.”

These are all real issues, experts say: Health plans and pharmacy benefits managers do share some of the blame for the high costs that Americans are paying out of pocket. Increased generic competition should do something to help get more cheap drugs on the market. The hospitals drug program might be in need of more scrutiny.

But they all have something else in common: They aren’t about the list prices that pharmaceutical companies set when they introduce a new drug. Lowering the out-of-pocket costs that normal people feel is worthwhile, Walid Gellad, a co-director at the Center for Pharmaceutical Policy and Prescribing at the University of Pittsburgh, told me. But that won’t bring down the gross costs of prescription drugs.

And as long as those costs remain high, somebody is going to pay the bill. Health insurers could be required to reduce what some people pay out of pocket for medicine, but if they are, then they will simply raise premiums on everybody to make up for it.

“Everybody still talks about drug prices, but most of the time, they’re talking about the cost sharing for drugs,” Gellad said. “The efforts that we’ve seen so far are meant to reduce what people pay, but they’re not going to reduce drug prices.”

“They’re just going to raise premiums, or try to offset it another way,” he said of insurance plans. “Someone’s gonna pay the price if the price doesn’t come down.”

So the systematic problems are still there — though pharma would counter that their medicines provide a unique value to the health care system, keeping costs down over the long term, and dismiss critics who they say won’t be satisfied unless the industry takes a direct hit.

But the point is: Nobody, especially President Trump, is really talking about prices anymore.

“Patient out-of-pocket costs are certainly a problem that needs to be addressed,” Sachs said, “but it can’t be the solution to drug pricing.”

Pharma is trying to behave itself — sort of — to avoid Trump’s wrath

Allergan CEO Brent Saunders famously promised in fall 2016, before Trump’s win but while drug prices were still the dominant health care issue, that his company would not raise any list prices higher than 10 percent as part of a “social contract.”

Other companies have done the same. Long frustrated that industry outsiders like Shkreli have given their sector a bad name, the big-time pharmaceutical firms have been doing what they can to avoid bad headlines and risk bringing Trump’s ferocious anger back down on them.

“The restraint, I think, is because the industry’s savvy and they’re not tone-deaf to the tenor of things,” the industry insider told me. “Nobody is smarter than the people in this industry. It’s not a cynical view. It’s the opposite. They are not going to do stupid, self-destructive things.”

In other words, the pharmaceutical industry is hoping to stay out of the headlines — and Trump’s Twitter feed — by keeping their price hikes in check. Just this month, drugmakers announced a new spate of price hikes, but they largely stayed within that 10 percent limit, Reuters reported.

It’s smart politics for the drug industry, but experts warn against creating a new status quo where 10 percent raises are seen as the norm — or, worse, as restraint.

“If we say it’s okay to have single-digit price increases, we’re saying it’s okay for a price to double in seven or eight years. No one should think that that’s okay, or that’s self-policing,” Gellad said. “The idea that high-single-digit price increases are somehow okay is mind-boggling.”

It also gives the false impression that list prices are the only way drug companies can pad their profits.

Allergan — the trendsetter on self-imposed limits on price increases — got into trouble with a federal judge late last year for trying to sell its expiring patents on some of its drugs to a Native American tribe to extend the life of the patent and maintain its monopoly on the drugs for a while longer, which would bring in millions of dollars in additional revenue.

The convoluted scheme never attracted the same level of outrage as Martin Shkreli or the price hikes for EpiPens and insulin, perhaps because it dealt with the minutiae of US patent law, an area essential for pharmaceutical firms but far more impenetrable to the average American than tripling a drug’s price.

The Trump presidency isn’t over, of course, not by a long shot. Industry officials are still on guard after his vitriolic entry into office.

Right now, HHS is actually reviewing a waiver for Massachusetts to allow its Medicaid program to more aggressively restrict access to certain drugs as a negotiating tactic with drugmakers. How the administration responds could signal whether it is willing to take steps to deliver on Trump’s promises.

But so far, Trump is taking it easy on pharma.

“They want to lower drug prices without hurting the industry’s revenue,” Gellad said. “Everything the administration has done so far seems to fall in that category.”

Sourse: vox.com