The people of the United States possess an unusual connection with soy, a critical and broadly grown plant across the globe.

Many of us link the protein-rich, pale yellow seeds of soybeans to specialized vegetarian fare like tofu, soy milk, and plant-based patties (thus the dismissive label “soy boy” aimed at vegans). Yet the truth is, virtually everyone consumes soy frequently, and non-vegetarians probably ingest more soy than individuals who abstain from meat, not less.

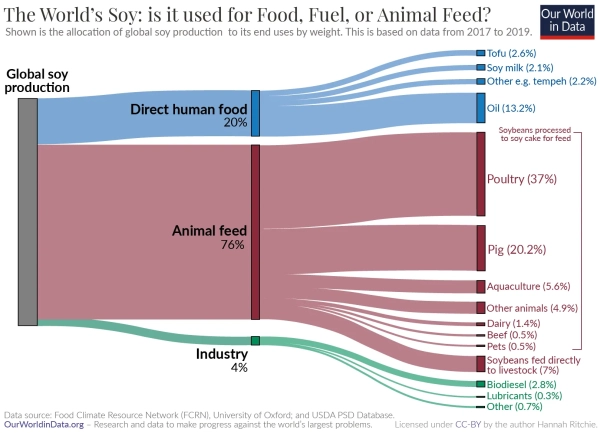

This is attributable to the fact that soy constitutes the hidden foundation propping up contemporary, meat-centric eating patterns. The vast bulk of soy on the planet — approximately 77 percent — is cultivated to nourish not people, but the billions of chickens, pigs, and cattle bred to sustain us, forming the primary protein basis in animal diets.

Processing Meat

A newsletter dissecting the impacts of the meat and dairy sectors on all aspects of our environment.

Email (required)Sign UpBy submitting your email, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Notice. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Our society’s great need for meat clarifies why the US generates such a high amount of soy. Despite its history as an exclusively East Asian crop for items such as miso, soy sauce, and tofu, presently, nearly all soy growth is centered in the Americas. As emphasized by recent trade conflict news, the US is the second-largest soy producer after Brazil, and soybeans stand as our number one agricultural export. Over the past century, the unassuming bean has become as much a sign of American opulence as corn syrup and chicken nuggets.

Because its demand exists globally, yet its output is located in specific geographic regions, the soybean has obtained unusual geopolitical relevance as the most frequently traded agricultural item across the world. China, formerly the top soybean farmer worldwide, currently is the largest importer, purchasing most of its soy from both Brazil and the US, especially to feed its mass-produced pigs, chickens, and fish. Actually, in many years, China acquires the majority of US soy exports. In the meantime, Brazil has, in recent decades, evolved into an agricultural powerhouse owing in part to its soy sales to China. In an attempt to reduce its reliance on imports, China is even endeavoring to create livestock foods that have a reduced soy content.

When delicate international associations of this kind undergo strain — as might occur if a prominent soy-producing country’s leader initiates a trade war with no justification — export-dependent industries feel the repercussions. US soybean farmers currently face this very situation. This year, in response to President Donald Trump’s stringent tariffs, Beijing enacted substantial tariffs on American soybeans, practically eliminating US soy sales to China. The overall value of US soy exports in the first half of the year has shrunk by almost a quarter since 2024, and according to recent data from the US Department of Agriculture, Chinese traders have not placed orders for US soy from the ongoing harvest year, which commenced on September 1. (Around this time last year, they had already requested millions of tons.)

American soy producers, as they observe China buying record quantities of soy from Brazil and Argentina while avoiding the US, are understandably exasperated. Predictably, the White House has signaled it will allocate funds to farmers to compensate for their deficits, as it previously did during Trump’s inaugural trade war in 2018.

Despite all this, the significance of this dispute might be less than apparent. Soy exports do not truly bear economic importance to the US — the entirety of agriculture constitutes less than 1 percent of our economy — although they are indeed significant to regional economies in agricultural states. While Trump’s trade war is futile and detrimental to the nation on the whole, the grounds for especially aiding farmers — using tariff revenue collected from all Americans — are political rather than economic. Customarily, we subsidize agriculture because producing food is crucially important — we have a need to eat — but there is no legitimate reason (other than the voting influence of Iowa farmers) to regard the export of animal feed for China’s pigs as a national cause deserving perhaps $10 billion.

We should all exhibit less concern regarding the condition of the soybean industry. According to numerous experts, it will likely be acceptable. Instead, one way to understand soy is as a remarkable and valuable technology that, when utilized with greater wisdom than we currently demonstrate, can sustainably nourish a world inhabited by 8 billion people and still growing. The trade war is largely a distraction, though it could, in a minor way, push us even farther from that objective.

Why we use soy

Occasionally, an extremely confusing post will circulate widely online, placing blame on vegans for the global soybean sector’s destruction of tropical rainforests.

It may come as a shock, but these assertions are, as a matter of fact, incorrect. Only roughly 13 percent of the world’s soy output is processed into soybean oil consumed by humans — found in common prepackaged goods like crackers, cookies, and salad dressings — and below 6 percent is used for the foods potentially associated with the vegan section of the supermarket.

However, the reality goes beyond the fact that more soy is used for animal goods than food for human consumption. Soy is utilized excessively and inefficiently in the production of animal goods. When feeding soy to farmed animals, we squander more land and more calories than we would if we directly consumed the crops.

This implies that rising global meat consumption over the last several decades has sped up the clearing of some of the earth’s most ecologically vital terrain, such as the Amazon rainforest and the Brazilian Cerrado, for the purpose of farming livestock and growing feed crops, which includes soy.

Nevertheless, bear in mind: as long as people eat animals, the animals must eat something. Alongside corn, soy has arisen as one of the preferential crops, since it is essentially the most fruitful, land-sparing — and in turn, least environmentally harmful — source of protein on Earth.

“Don’t cast blame on the soy,” noted Timothy Searchinger, a senior research scholar at Princeton University and a major authority on the planetary effects of agriculture. “If it was not soy and we were escalating meat [consumption], and we had to nourish the meat using lentils, we would require three times the amount of land to nourish the meat with the lentils, and we would all be cursing lentils.”

In other words, soy constitutes the least unfavorable option for nourishing livestock; however, livestock do not represent a sound use of soy. The need for animal feed now escalates together with another major global user of soybeans, which likewise wastes land that could otherwise be conserved to maintain wild, biodiverse ecosystems storing carbon. This involves biofuels, or liquid fuels produced from agricultural crops to run vehicles, trucks, planes, and various other machinery. Once hailed as a sustainable alternative to fossil fuels, numerous climate specialists now think that biofuels such as corn ethanol and soy biodiesel are just as detrimental, if not worse, in terms of carbon emissions than their petroleum equivalents when their land use is assessed.

Nevertheless, biofuels stubbornly remain rooted in the US energy composition via guidelines such as the federal Renewable Fuel Standard, supported by politically influential commodity crop industries (which candidly acknowledge that the fundamental goal of biofuel policy lies in guaranteeing them a market). Over the past 20 years, an increasingly larger fraction of US soybean oil has been diverted to biofuels, rising from nearly 15 percent in 2010 to a predicted amount of over half during the 2025-2026 harvest year.

Simultaneously, this rerouting of US farmland to cultivate fuel is pushing genuine food production to newer territories, generating the destruction of irreplaceable woodlands elsewhere across the globe — an expected market outcome known as indirect land-use change. Soybean oil employed in packaged supermarket foods can be readily replaced by other vegetable oils, for example, canola, sunflower, and palm, Richard Sexton, an agricultural economist at the University of California, Davis, clarified. So as additional US soybean oil gets channeled into fuel containers, the abundant rainforests of Southeast Asia — among Earth’s most crucial carbon sinks and the native habitats of our critically threatened great ape relatives, orangutans — are felled to cultivate oil palm.

In Sexton’s words, “We are deforesting Indonesia and Malaysia as a result of our biofuel policies.”

What will the trade war mean for the future of soy?

Irrespective of whether we feed it to pigs and chickens, or trucks and tractors, the principle remains unchanged: Humans consume excessive amounts of soy, a spectacularly fruitful crop, for exceedingly unproductive objectives.

However, it does not mean that it is favorable that American farmers now face difficulty selling their soybeans. Due to the fact that soy represents a global market, any soybeans that China refrains from purchasing from the US, it has the ability to obtain from South America. And South American soy proves worse for the planet than US soy, since it stems from a region where significant land clearing for farming continues to transpire. “If you are planning to transfer production from the US to Latin America, you ultimately face greater carbon costs, together with biodiversity costs,” Searchinger noted.

It’s unclear, nevertheless, whether the trade war will meaningfully transfer production from the US to South America. For that to transpire, South American soybean prices must be high enough to entice farmers to amplify production beyond their initial plans. There exists partial evidence to support this— US soy prices have undergone depression this year as a result of the lack of Chinese demand, whereas export prices in Brazil have been lifted — though the counterfactual remains indefinite, as does the duration of these price effects.

Source: vox.com