Four drug companies on Monday reached a last-minute settlement with two Ohio counties that will let them avoid trial over their role in the opioid epidemic, but it doesn’t put an end just yet to the thousands of other lawsuits the four companies and others face.

The settlement will require drug distributors McKesson, AmerisourceBergen, and Cardinal Health as well as generic opioid painkiller maker Teva Pharmaceuticals to pay at least $260 million to Cuyahoga and Summit counties, according to the Washington Post and New York Times. The deal leaves Walgreens, which distributes opioids, as the lone defendant that has not settled, but its case was postponed after a trial was originally set to start Monday.

Previously, the counties had reached a $20 million settlement with pharmaceutical giant Johnson & Johnson. A court separately ordered Johnson & Johnson to pay Oklahoma $570 million in another recent case.

Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals also reached a $30 million settlement with Cuyahoga and Summit counties.

Vox has launched The Rehab Racket, an investigation into America’s notoriously opaque addiction treatment industry. We’re crowdsourcing patients and families’ rehab stories, with an emphasis on the cost of treatment and quality of care. If you’d like help our reporting by sharing your story, please fill out this survey.

If you or someone you know needs addiction treatment, you can seek help online through SAMSHA’s treatment locator or by phone at 1-800-662-4357. If you need more information, Vox put together a guide for how to find good addiction treatment.

And Purdue Pharma, maker of OxyContin, reached a broader settlement to settle all the lawsuits against it — not just those from the two counties — in a deal worth at least $10 billion to $12 billion, although dozens of states are still contesting that settlement.

The latest settlement between the two counties and four drug companies comes after the defendants in the litigation rushed over the weekend to get a deal to end the thousands of lawsuits facing pharmaceutical firms over their role in the opioid epidemic. But a bigger deal could not be reached, so the companies have settled the smaller case with the two Ohio counties, which is known as a “bellwether trial,” in the meantime to buy more time for hashing out a deal and avoiding court. US District Court Judge Dan Aaron Polster has pushed for a single, big legal settlement.

Since the opioid epidemic began in the 1990s, more than 200,000 people have died of painkiller overdose deaths, with another roughly 200,000 dying from other opioids — in many cases, after using painkillers first.

The hope with the lawsuits is to not just hold the drug manufacturers and distributors allegedly involved in the opioid epidemic accountable for the crisis, but also force them to pay for addiction treatment that could help combat the epidemic. Treatment is notoriously underfunded in the US, with experts in recent years calling on the federal government to invest tens of billions of dollars in building up treatment infrastructure. (For reference, a 2017 study from the White House Council of Economic Advisers linked a year of the opioid crisis to $500 billion in economic losses.)

Some politicians and activists, including several presidential candidates, have gone further than the lawsuits — demanding not just that opioid manufacturers and distributors pay for the financial harm they caused, but that they are held criminally liable.

“You can go to prison for accidentally killing one person with your car. That’s the minimum standard,” Rick Claypool, a research director at Public Citizen, told me. “The idea that you can run a company and cause societal-level devastation and walk away from that relatively unscathed is mind-boggling.”

At least for now, though, the drug companies are at least facing financial consequences.

How drug companies helped cause the opioid epidemic

The opioid epidemic can be understood in three waves. In the first, starting in the late 1990s and early 2000s, doctors prescribed a lot of opioid painkillers. That caused the drugs to proliferate to widespread misuse and addiction — among not just patients but also friends and family of patients, teens who took the drugs from their parents’ medicine cabinets and people who bought excess pills from the black market.

A second wave of drug overdoses took off in the 2000s when heroin flooded the illicit market, as drug dealers and traffickers took advantage of a new population of people who used opioids but had either lost access to painkillers or simply sought a better, cheaper high. And in recent years, the US has seen a third wave, as illicit fentanyl offers an even more potent, cheaper — and deadlier — alternative to heroin.

It’s the first wave that really kicked off the opioid crisis — and where opioid makers and distributors come in.

Manufacturers of the drugs misleadingly marketed opioid painkillers as safe and effective, with multiple studies tying the marketing and proliferation of opioids to misuse, addiction, and overdoses. Opioid makers like Purdue, Johnson & Johnson, and Teva are all accused of playing a role here.

As a group of public health experts explained in the Annual Review of Public Health, the companies exaggerated the benefits and safety of their products, supported advocacy groups and “education” campaigns that encouraged widespread use of opioids, and lobbied lawmakers to loosen access to the drugs.

Meanwhile, distributors like McKesson, AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, and Walgreens are accused of letting the drugs proliferate with insufficient oversight, when they should have known opioids were going to people who were misusing the drugs. The data shows that, in some counties and states, there were more prescribed bottles of opioids than there were people — a sign that something was going wrong.

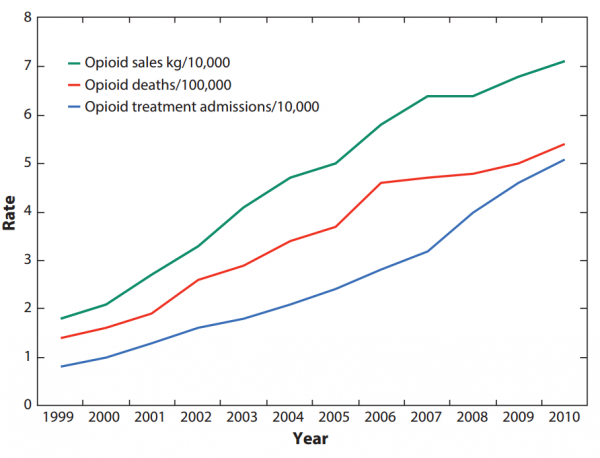

The result: As opioid sales grew, so did addiction and overdoses.

It’s not just that the opioids were deadly; they also weren’t anywhere near as effective for chronic non-cancer pain as the companies claimed. There’s only very weak scientific evidence that opioid painkillers can effectively treat long-term chronic pain as patients grow tolerant of opioids’ effects — but there’s plenty of evidence that prolonged use can result in very bad complications, including a higher risk of addiction, overdose, and death. In short, the risks and downsides outweigh the benefits for most chronic pain patients.

Yet even as these risks became apparent over the years, drug companies continued marketing, selling, and distributing opioids widely. So different levels of government are now trying to hold the firms responsible — and that’s why we’re seeing all of the latest legal settlements.

For more on the lawsuits against opioid companies, read Vox’s explainer.

Vox is investigating the high cost of addiction treatment in the US. Follow along as German Lopez reports on this important issue that affects millions of people each year. Sign up to get notified about new stories and project updates.

Sourse: vox.com