Each week, Richard Brody picks a classic film, a modern film, an independent film, a foreign film, and a documentary for online viewing.

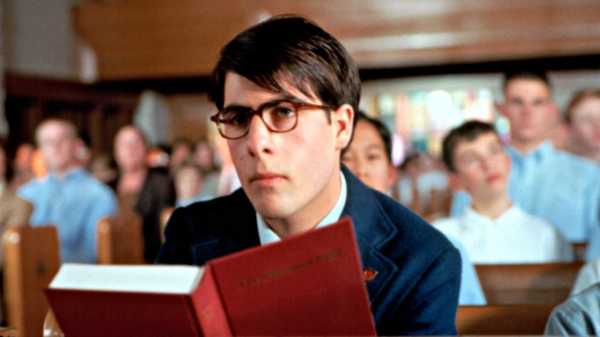

“Rushmore”

Photograph from Walt Disney Co. / Everett

The release of Clint Eastwood’s “The 15:17 to Paris,” in which the three young American men who thwarted a terrorist attack on a train in France in 2015 play themselves, brings to mind other great films featuring nonprofessional actors. Jason Schwartzman is one of the most original actors of his generation, but he started out as an astoundingly original non-actor: when he went, as a teen-ager, to an audition for Wes Anderson’s second feature, “Rushmore,” he had never been to an audition or even read a script. Schwartzman’s performance as Max Fischer, a hubristic prodigy, is itself prodigious, and it’s all the more so inasmuch as Anderson (who wrote the script with Owen Wilson) is a meticulous director, a virtual choreographer of gestures and inflections. The drama is the tale of a dramatist (Max is a playwright and director) and a self-dramatist (who vainly conceals and fabricates his origins), a desperate fifteen-year-old romantic whose ideas of courtship (aimed at a teacher, played by Olivia Williams) are beyond his years and whose deceptive and vengeful schemes—against his main rival, a melancholy businessman (Bill Murray), who is also his mentor and friend—are foolishly childlike. It’s a teeming, sophisticated, scintillatingly clever movie, and Schwartzman, his first time out, gives a copious, complex performance to match; as his subsequent career has proved (including his performance in “Golden Exits,” which opens this weekend), his natural virtuosity has only grown deeper.

Stream “Rushmore” on Amazon, Google Play, and other services.

“The Best Years of Our Lives”

Photograph from Everett

William Wyler’s vast, urgent, critical, rapturous melodrama “The Best Years of Our Lives,” from 1946, a sort of cinematic relaunch of American society in the wake of the Second World War, is set in a small Midwestern city to which three veterans are returning home. One is a former drugstore soda jerk who’s now a hero pilot (Dana Andrews); another is a middle-aged bank executive whose experience in war makes him uneasy with bourgeois verities (Fredric March). The third, a young man named Homer, who returns home grievously wounded (he has lost his hands and uses prostheses), is played by Harold Russell, a war veteran who suffered such an injury in a training accident and who had never acted in a movie before. Wyler frankly considered Homer’s—which is to say, Russell’s—deftness with his prosthetic hands, as well as the frustrations and even dangers that his disability imposed. The movie also dramatizes, with romantic tenderness and insight, Homer’s altered self-image, his intimate inhibitions in his relationship with his fiancée (Cathy O’Donnell). Russell’s plain, frank speech, along with his determined gait and searching gaze, make his performance as effective and moving as it is historic.

Stream “The Best Years of Our Lives” on iTunes and Vudu.

“Daddy Longlegs”

Photograph from IFC Films / Everett

Ronald Bronstein has directed one feature, “Frownland” (released in 2007), and it’s one of the seminal works of the modern independent cinema. In “Daddy Longlegs,” from 2009, the filmmakers Josh and Benny Safdie recruited Bronstein to play the lead role of Lenny, a film projectionist (Bronstein’s real-life job at the time) who’s the father of two young sons (played by Sage and Frey Ranaldo) and is a near-total fuckup. Lenny, divorced, has custody of the boys for two weeks, but he also has work; a loving father, he’s also a cyclone of chaos and reckless impulses, playful and pugnacious, fiercely protective yet cavalierly thoughtless, driven by need and trouble to wild schemes into which the boys are dragged. The Safdies orchestrate the turbulence deftly and ardently, but Bronstein, himself a master of onscreen disaster, seems to stretch and push the action to create the frame from within, directing onscreen alongside the Safdies. (He’s now their close behind-the-scenes collaborator, co-writing and co-editing their recent films “Heaven Knows What” and “Good Time,” which stars Robert Pattinson.)

Stream “Daddy Longlegs” on Amazon, the Criterion Channel at FilmStruck, and other services.

“Daisies”

Photograph from Everett

The Czech director Věra Chytilová’s 1966 comedy “Daisies” is a gleefully derisive comedy and a madly imaginative fantasy, starring the nonprofessional actors Jitka Cerhová and Ivana Karbanová as two young women named Marie who make a mockery of the solemn rituals of Czechoslovakian society in the age of the Iron Curtain, from formal dining with doughy middle-aged men to women’s thrifty domestic labor to factory production to military pomp to Communist Party pageantry. The women’s extravagant, windup-like performances are matched by Chytilová’s riotous audacity, with florid color scenes intercut with black-and-white ones, luridly tinted images, cartoonish fast motion, rapid-fire subliminal editing, and collage-like decorative fantasies. The frantic and absurdist dialogue meshes with the wildly ritualistic disorder to dramatize the rigid society’s indifference and hostility to women’s needs and desires, its repression and destruction of youthful imagination. After the film’s release, Chytilová was banned from filmmaking until 1975.

Stream “Daisies” on the Criterion Channel at FilmStruck .

“I Called Him Morgan”

YouTube

In the documentary “I Called Him Morgan,” from 2017, the Swedish filmmaker Kasper Collin considers the life and death of the great jazz trumpeter Lee Morgan, who, at the age of thirty-three, in 1972, was shot to death in a Lower East Side night club by his common-law wife, Helen Moore, a.k.a. Helen Morgan. Collin was able to include on the film’s soundtrack clips from the only extant recorded interview with Helen Morgan (who died in 1996), and he also interviews leading musicians who knew the couple and worked with Lee Morgan, including Wayne Shorter, Charli Persip, and Jymie Merritt, as well as Morgan’s friend Judith Johnson, who was with him the night of his death. With their insightful, passionate recollections, joined to archival sequences showing where Helen Morgan lived and where Lee Morgan played, plus classic footage of the musicians at work from the fifties through the early seventies, Collin evokes the powerful personalities at the center of the film, as well as the crises of the age, including racist policies and practices and the prevalence of heroin addiction, which marked their life and work.

Stream “I Called Him Morgan” on Netflix, Amazon, and other services.

Sourse: newyorker.com