Many preppers’ fears are not based on speculative, sci-fi-style catastrophes but on disasters that have already happened.

Several years ago, a New York City firefighter named Jason Charles read the novel “One Second After,” by William R. Forstchen, and decided to change his life. In the book, an electromagnetic pulse goes off and sends the United States back into the Dark Ages; in its foreword, Newt Gingrich writes that this technology is not only real but terrorists know about it. “It was pretty much a green light for me to start prepping,” Charles says. The latest episode of The New Yorker’s “Annals of Obsession” video series centers on doomsday preppers—people who aim to equip themselves with the skills and materials they would need to survive a world-ending calamity. Charles is now the organizer of the group N.Y.C. Preppers, which teaches city dwellers how to fend for themselves. He says that he has stockpiled enough supplies that, if the worst came to pass, he would be able to be self-reliant for a year and a half.

Robyn Gershon, a public-health professor at N.Y.U. who specializes in disaster preparedness, concedes that, in the age of global warming, it is not so outlandish to be thinking about the apocalypse. Per the “push-pulse theory of extinction”—a theory devised to explain the mass death of the dinosaurs—any strain on an ecosystem leaves the species in it far more vulnerable to cataclysm. Today, climate change and rising sea levels put us at greater risk of being wiped out by a disastrous event, such as a pandemic or a supervolcano.

Revealingly, however, many doomsday preppers’ fears are not based on speculative, sci-fi-style catastrophes but on disasters that have already happened. “Watch a documentary about Katrina. Look at something about Sandy, years afterwards. Look at Puerto Rico right now,” Scott Bounds, a member of N.Y.C. Preppers, says. “You have to realize that people are not going to come take care of you. You really have to be able to take care of yourself.”

Judging by that rationale—“people are not going to take care of you”—the impulse to prep is as much a response to governmental failings as it is to apocalyptic fantasies. During Hurricane Harvey, Houston residents relied on the “Cajun Navy”—generous volunteers with boats—to evacuate them. After Hurricane Maria, a Harvard study found that the Trump Administration’s neglect of Puerto Rico caused four thousand six hundred and sixty-five deaths, many because of interruptions to medical care. And, this week, as historic fires engulfed huge areas of California, the President accused the state of “gross mismanagement of the forests.” Charles, outlining his vision of a doomsday scenario, says, “It’s when law enforcement stops going to work, that’s when the breakdown begins. Now you’re talking about a free-for-all, every-man-for-themselves kind of deal.” Whether or not the apocalypse comes, it seems like that breakdown is already under way.

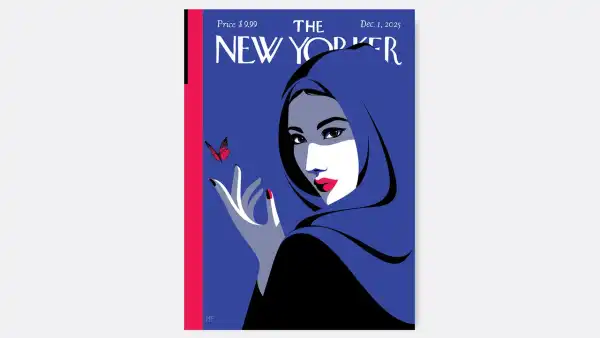

Sourse: newyorker.com