I am writing this a day after my favorite sister’s birthday. She was very dear to me. She would have been sixty-nine this fall. She died two years ago, another casualty of M.S. and poor-black-girl-in-America life. My sister’s absence became even more pronounced for me when the poet, playwright, and author Ntozake Shange died on October 27th. Shange was just seventy when she passed and had been living in an assisted-care facility in Maryland. When my sister died, she had been living in an assisted-care facility in Brooklyn. My sister’s birthday, Shange’s death—each consumed me and left me sitting in the middle of a kind of loneliness which I do not want to bear but had to bear, because I wanted to tell you something about these women, their strengths and weaknesses, and the profound effect that each had on my life and my consciousness, as a writer and a feminist.

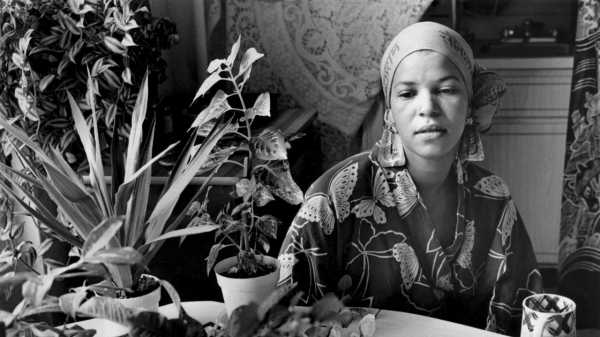

I never met Shange (when I wrote about her in 2010, our interview was conducted via email; it was physically complicated for her to travel), but of course she was always there in my life and in the lives of all those colored people and white people who cared about poetry and singing and dance and jazz and salsa and politics and women and how to make all those things intersect, on the page and in your body. Style-wise, the young Shange resembled my sister, down to the leotard tops, scarves, earrings, and flowing skirts (with harem pants underneath) that they both sported in the nineteen-seventies. Still, it was a happy shock to see Shange’s image on the subway and on buses when the artist and graphic designer Paul Davis’s remarkable poster for her acclaimed theatre piece “for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf” began to appear all over town. That was in 1976, when Shange’s “choreopoem” went from a wildly successful run at the Public Theatre to the Booth Theatre, on Broadway, where it ran for more than two years. (This was the second play by a black woman to reach Broadway; Lorraine Hansberry’s drama “A Raisin in the Sun,” from 1959, was the first.) The shock that I felt looking at Shange in Davis’s color—finally, my poet-sister was being seen! all poet-sisters were being seen!—was only surpassed by seeing the performance itself, a whole world filled with colored female bodies and all those words. Words that said we—my sister, myself, your sister, and all the aunties and mothers—weren’t just poets in the kitchen, as the author Paule Marshall had put it, but potentially poets that could change the larger world.

Shange was born in New Jersey in 1948 and named Paulette Williams. When she was a young child, Shange and her family relocated to St. Louis, where they lived in an upper-middle-class enclave of the town, a segregated universe. Her father, Paul T. Williams, was a surgeon, and her mother, Eloise, was an educator and psychiatric social worker. The couple considered black luminaries ranging from W. E. B. Du Bois to Chuck Berry to be solid friends and acquaintances. Growing up during the era of Brown v. Board of Education, Shange was bussed to white schools, and the racism she encountered there unhinged her. I don’t think she ever fully recovered from the slurs and verbal arrows that grazed and pierced her flesh. (The Williams family returned to New Jersey when Shange was thirteen.) Actually, there is no “recovery” from such awfulness; you either carry it with you and do something with it, or it kills you, incrementally.

And what has always been astonishing to me about black artists and women artists, in particular, is how they take the shit that’s been ladled out and make something of it while continuing to look for meaning in this life. Politics were integral to Shange’s existence, and to my sister’s. As what a friend called “seventies girls,” they were partly raised in the nineteen-fifties, and so lived in a post-hippie, Black Arts-movement-informed society, one that supported the brothers while trying to work out what being “womanist” meant. After Shange moved east to attend Barnard College, she began hanging out with the Young Lords, a largely Hispanic group that encouraged and supported a feminist view. (The Black Panthers didn’t.) At Barnard, Shange was split: she was a privileged black girl who discovered her stories in the street, far from the narrative her class and race had prescribed for her. The schism was deep. As it was for many women raised in conventional families, getting married was supposed to be the thing, right? So, there was an early union that ended relatively quickly, but what to do as a colored girl who didn’t want any of that? Shange tried to commit suicide a number of times. She was defensive, vulnerable, and bitter. (It would be years before she was diagnosed as having bipolar disorder.)

But after Shange graduated with honors from Barnard, in 1970, the world started to open up a bit, or, more specifically, she started to create a world that she could inhabit. In 1971, she changed her name from Paulette Williams to Ntozake Shange, which is Zulu for “she who comes with her own things and walks like a lion,” and, by 1973, she had a master’s degree in American Studies from U.S.C. and had relocated to the Bay Area to teach women’s studies and humanities at several colleges. In 1973, I was thirteen, and my sister’s influence had already left its mark. She had always believed in the power of education, having had, as a young girl, a formative experience with a public school teacher who loved her. This was not standard. But it was enough love to inspire my sister to become an educator, a very good teacher in the same school system that had produced the two of us. But, later on, this system failed not only many of its students but also my sister. In addition to having to buy her own art supplies for her classes, she worked twelve-plus-hour days to make a difference. Eventually the ignorance and neglect she confronted where she taught contributed to her illness, and she retired. But nothing could rob her of her love of poets and artists and education, and the sweetest memories I have of her are like the writing of hers I saw and remember: tender, lyrical, true.

When my little brother and I were kids, our mother was often ill, and my sister had to take us with her to lots of places. Sometimes we went to The East, a cultural center in Bedford-Stuyvesant, where we heard jazz musicians and saw black-nationalist plays. My sister was in her element in this environment, and, during the inevitable Q. & A.s that followed such performances, she asked questions and made observations that would have gotten her a seat at Harvard, or Berkeley, had she known, had any of us known, how to access power to get power. But power was anathema to us because it had worked us with its shaming power forever and forever. We were welfare babies whose family privacy was occasionally invaded in exchange for certain benefits, like food. What did we know about getting what you need in a wanting world? Because of her class, Shange, at least, had access to the possibilities. She was not hobbled by a lack of knowledge about what one could take from life. I grew up in a world where life happened to you and it was your job to try to escape its worst, or make do. In the Bay Area, Shange met other women who were discovering their voices, and, inspired by Judy Grahn’s seminal collection, “The Common Woman,” from 1969, the burgeoning author began writing stories about women’s lives and performing them in bars and clubs. As her work began to take shape, she found a title: “for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf.”

It is interesting to live with an artist. They educate themselves bravely in public. I loved watching my sister get up. I loved her thrift-store findings, her skill on the trumpet (just like Cynthia in Sly and the Family Stone!), and, in general, how she was becoming herself in front of her most dedicated audience: me. Our mother often criticized my sister’s makeup, her brilliant sartorial voices; couldn’t she see that my sister was making a poem of herself? Shange, in her introduction to the published version of “for colored girls,” wrote a wonderful piece about her years in Northern California as her choreopoem began to take shape, and she was committed “not to do less than—at all costs not to be less woman than—our mothers, from Isis to Marie Laurencin, Zora Neale Hurston to Kathe Kollwitz, Anna May Wong to Calamity Jane.” Shange recalls her time in the Bay Area:

Knowing a woman’s mind & spirit had been allowed me, with dance I discovered my body more intimately than I had imagined possible. With the acceptance of the ethnicity of my thighs & backside, came a clearer understanding of my voice as a woman & as a poet. The freedom to move in space, to demand of my own sweat a perfection that could continually be approached, though never known, was poem to me, my body and mind eclipsing, probably for the first time in my life. Just as Women’s Studies had rooted me to an articulate female heritage & imperative, as explicated by [teachers] Raymond Sawyer & Ed Mock insisted that everything African, everything half way colloquial, a grimace, a strut, an arched back over a yawn, waz mine.

It is Shange’s ownership of her ass and mind that contributes to the freedom and wildly imaginative authority of her early dramatic work. After the timeless “for colored girls,” there were a few stumbles on the stage, such as her flawed but brilliant “A Photograph,” which was produced at the Public Theatre, in 1977, but she couldn’t help but but be out there—it had taken so long for her to be herself. 1979 yielded the still exciting “spell #7,” which also premiered at the Public, and it’s a measure of how devoted to trend our American theatre still is that “spell #7” isn’t produced more often. (In 1981, Shange wrote, “As a poet in american theater / i find most activity that takes place on our stages overwhelmingly shallow / stilted & imitative.”) But Shange was not a traditional playwright or artist, and her scripts demand an amount of invention and freedom from the director and the cast that is equal to the words she gives them. “spell #7,” is about black performers lamenting a world that doesn’t see them as artists. Left to their individual and collective imaginations, they tell stories about themselves, and about the world. Responding to the tiresome limitations imposed on her life as a black female performer, Lily, who supports herself as a barmaid, creates a performance piece for herself. And the crux of her story is about black women equating beauty with having “good” hair.

lily (illustrating her words with movement)

i’m gonna simply brush my hair. rapunzel pull yr tresses back into the tower. & lady godiva give up horseback riding. i’m gonna alter my social & professional life dramatically. i will brush 100 strokes in the morning/ 100 strokes midday & 100 strokes before retiring. I will have a very busy schedule. between the local trains & the express/i’m gonna brush. i brush between telephone calls. at the disco i’m gonna brush on the slow songs/i don’t slow dance with strangers. i’ma brush my hair before making love & after. i’ll brush my hair in taxis. while window-shopping. when i have visitors over the kitchen table/i’m a brush…i dream of chaka khan/chocolate from graham central station with all seven wigs/ &medusa. i brush and brush. i use olive oil hair food/&posner’s vitamin E. but mostly I brush & brush. i may lose contact with most of my friends. i cd lose my job/but i’m on unemployment & brush while waiting on line for my check…nothing in my dreams suggests that hair brushing per se/has anything to do with my particular kinda hair. a therapist might say that the head fulla hair had to do with something else/like: a symbol of lily’s unconscious desires. but i have no therapist

Writing from the inside of her women, Shange made wonders, such as her short story, “Faye,” which we are lucky enough to have a recording of her reading. I fill up when Shange says that Faye is a woman who is very dear to her heart, because, when it comes down to it, that’s how I feel about many of the women in her plays and fiction. Somehow, because of the characters’ complications—complications which I sometimes recognize as my sister’s, and our sister’s, and our mother’s—I suddenly recall my dreams and realities about these women, despite knowing that these women are dying, or have died.

In 1980, Shange adapted Bertolt Brecht’s “Mother Courage and Her Children,” and I would have given anything to see that production, which starred the much missed Gloria Foster in the title role. The piece, which remains unpublished, needs to be put up again, if only because Shange unearths Brecht’s humor while adding a lot of her own. At the beginning, an army officer asks Mother Courage about her children. She explains who they are, and who their fathers are. Still the sergeant doesn’t get it. Doesn’t get how free a woman could be in the world with her children and choice of partners. Exasperated, Mother Courage says, “i aint tendin to insult ya/but ya lacking visions.” And couldn’t we say the same about a theatre that doesn’t keep pushing and pushing to get more out of a talent like Shange’s? “The Love Space Demands,” her stage work from 1991, contains all sorts of hilarious observations, such as those laid out in a poem called “intermittent celibacy”:

listening to bobby timmons & jackie wilson

does not encourage abstinence/

& it’s not like smokey misled me/either/

i cdn’t get nobody to let me be a bad girl &

how i tried to get one of them/to make me

a woman/

let me out the deprivations of virginity….

Holy Mary Mother of God

let somebody else come take me/

surely

The Lord God Almighty

gotta ’nough virgins

Before my sister died, she would tell me stories about our family, and about herself. She was an emotionally shy and private person and so lacked Shange’s boldness, but that didn’t make her any less of a poet. And, sometimes, as she talked, I remembered the girl she had been: beautiful and thin, playing handball in East New York with the guys in her pencil skirt; combing out the hair that Lily in “spell #7” could only dream of; dancing to salsa with a Puerto Rican boyfriend. One story my sister told me: when my sister turned sixteen, our mother gave her (as our mother had for her other three daughters) a string of pearls to celebrate. Virginal white pearls. My sister said that she was struck by the contrast between her hot flesh and the pearls, and, as she talked, I wrote it down because she couldn’t. But, in a way, she did write it down. I was merely transcribing her poem, what she felt and remembered, just as Shange transcribed what she felt and remembered—living, as she did, between the body that she was given and what she made of it, along with that mind, which was filled with so many stories that we’ll spend the next forever trying to catch up.

Sourse: newyorker.com