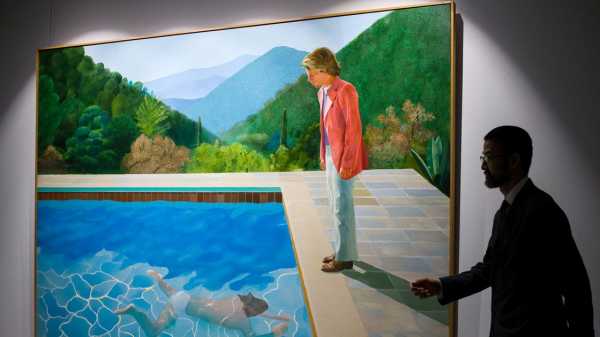

David Hockney is the world’s most expensive living artist as of Thursday night, when “Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures),” his big, color-soaked picture from 1972, sold at Christie’s New York for $90.3 million. It’s a dubious distinction, given that the eighty-one-year-old British painter won’t see a cent of the proceeds. In the U.S., artists aren’t entitled to royalties when a piece changes hands; they profit only the first time their work sells. The Hockney record topples Jeff Koons, whose balloon dogs sold, also at Christie’s, for a measly $58.4 million, in 2013. The painter, never press-shy, has issued no comment on the astronomical payout. (The identity of the buyer, as ever at auction, remains unknown.) Last week, at an event in his honor in London, Hockney did share his thoughts on the pre-auction hoopla with Reuters, saying, “I ignore it.” Still, it’s bound to feel good—vindicating, even—for the L.A.-based painter, whose exuberant figuration was, until recently, considered the visual equivalent of easy-listening music by the art-world intelligentsia.

Even more gratifying than the interest of an anonymous billionaire, probably, were the half-million people who turned out to see the painting in Hockney’s retrospective at the Tate Britain last year. (The artist was a record-smasher there, too, bested only by Henri Matisse in the annals of the museum’s attendance.) But too often these days, when we talk about art, we talk about money. To cite just one example, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s name is now synonymous with the phrase “more than a hundred and ten million dollars.”

“Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures)” deserves the overused label “masterpiece,” but it’s not a better picture today than it was forty-six years ago, when it sold at the Andre Emmerich gallery, in New York, for eighteen thousand dollars. Trophies and masterpieces aren’t the same thing, as anyone who has seen Leonardo da Vinci’s half-billion-dollar “Salvator Mundi” can attest. Reminiscing recently about his attraction to the subject of pools—he painted about twelve, then moved on—Hockney said, “You can look at the surface of the water or you could look through it.” The market is a shallows, reflecting art as an unregulated and increasingly obscenely priced financial instrument; the real value of a great painting has an unquantifiable depth. I just hope that Hockney’s beautiful picture is bound for a wall and not a crate in a freeport.

Sourse: newyorker.com