Illustration by Cari Vander Yacht

The word of 2018 is “justice,” according to Merriam-Webster. The art world paved the way last year, when the collector and philanthropist Agnes Gund launched the Art for Justice Fund (with the Ford Foundation), dedicated to criminal-justice reform. Gund kickstarted the fund with a hundred million dollars, roughly two-thirds of the proceeds from the private sale of a 1962 Pop-art masterpiece by Roy Lichtenstein. The fund’s stated mission of “art into action” could double as the motto of some of this year’s most powerful shows, including the philosopher-conceptualist Adrian Piper’s urgent outing at MOMA, and the poetically political photographs and installations, at the Whitney, of Zoe Leonard, who no longer chooses to be defined as an activist—but some labels just stick.

Zoe Leonard’s “The Fae Richards Photo Archives” (1993).

Photograph Courtesy Zoe Leonard and The Whitney Museum of American Art

The Art for Justice Fund’s 2018 grantees included several artists who provide a vital reminder that art is part of a social fabric beyond the endless cocktail party of collectors at fairs. (One such grantee is the Queens-based Cameron Rowland, a young Conceptualist who is as sensitive to his found materials as he is to his cause—imagine Duchamp galvanized by the institutionalized slavery of prison labor.) Why didn’t the news of Gund’s Lichtenstein sale, fuelled by philanthropic intentions, generate the kinds of hall-of-mirror headlines that last month’s ninety-million-dollar David Hockney auction did? Our increasing obsession with art as a financial asset is toxic—the word that Oxford Dictionary chose to sum up the spirit of 2018.

2018 in Review

New Yorker writers reflect on the year’s best.

I’d like to call for a moratorium on the Andy Warhol quote “Making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art.” But I can’t, because Warhol is undeniable, as we learned at “Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again,” the triumphant retrospective at the Whitney. The show was curated by Donna De Salvo, who has a preternatural talent for dismantling the received ideas of the contemporary canon and reconstructing history without breaking your spirit. By which I mean, if you like Andy served sixties-style, with the famous pictures of Campbell’s soup and Coca-Cola, this one’s for you. But the show also schools the snobs who cling to the misconception that the artist was washed up in his late years. Not incidentally, it’s jam-packed with beauty. The wall of framed collages of gold metallic high heels is haunting my New Year’s Eve-outfit dreams.

Speaking of beauty, MOMA reintroduced viewers to Charles White, the dazzling African-American draftsman. (He also made paintings, but they are blown away by his drawings and prints.) White was celebrated in life, but, after his death, in 1979, his reputation dwindled to that of an influential teacher (Kerry James Marshall was a student), owing in part to the sidelining of realism in the heyday of Minimalism. The exquisite pencil-and-oil-wash portraits he made in the course of his three-decade career valorize dignity, whether his subject was Harry Belafonte, Harriet Tubman, or a street preacher in aviator shades. In a year marked by perpetual crisis and relentless contention, White was a beacon of grace.

Charles White’s “Harriet” (1972).

Photograph by Paul Bardagjy. Courtesy The Charles White Archives

The world felt especially monstrous this year (for more on the subject, read Elizabeth Schambelan’s blazing essay in the December issue of Artforum), and Huma Bhabha fought monsters with monsters on the roof of the Met with her postapocalyptic, two-sculpture tableaux, “We Come in Peace.” As if. The pair of monumental painted-bronze figures, one prostrate, either in prayer or in fear, and the other a battle-scarred warrior-golem, flipped the script on conventions of beauty while perverting figurative traditions (Eastern and Western, ancient and modern) with pulp science-fiction. The Hilma af Klint retrospective, at the Guggenheim, had its own sci-fi twist: the kaleidoscopic color abstractions were painted via messages that the Swedish artist received from ancient spirit guides, who instructed her to exhibit them in a circular temple—like the building now housing them, which Frank Lloyd Wright designed long after they were made. Not since the Matthew Barney retrospective, in 2003, has the museum seemed as tailor-made for the art on display.

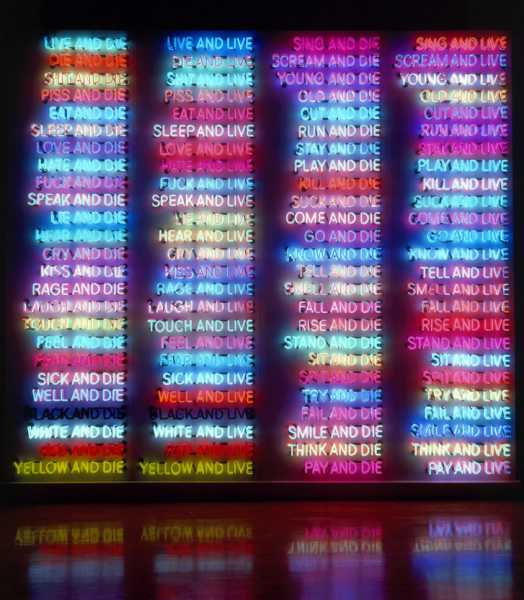

Bruce Nauman’s “One Hundred Live and Die” (1984).

Photograph by Dorothy Zeidman. Courtesy Bruce Nauman and Sperone Westwater, New York

I wish I’d seen the Bruce Nauman retrospective “Disappearing Act” when it was installed in Switzerland, at the Schaulager, in Basel. Word is that it was more harmonious—if one can ever use that word to describe the disruptive American genius—than it is in New York, where the show is split between MOMA and MOMA PS1. Regardless, seeing and hearing and feeling Nauman’s refractory five-decade career, as wrangled by the deeply attuned Kathy Halbreich, in her swan song at the museum (she left to run the Rauschenberg Foundation), made my uneasy year. I can’t think of sounder advice than the words greeting visitors to PS1, backward, as if seen in a mirror: “Pay attention mother fuckers.” Good luck in 2019.

Sourse: newyorker.com