For a lot of people, the major news stories in 2018 — from the midterm elections to the Brett Kavanaugh Supreme Court confirmation battle — just went by in an endless scroll of push notifications. It’s easy to get lost in that electronic sea, to see these as a series of discrete events without a broader through-line or impact.

But the year’s big events were parts of much more fundamental forces: deep social and political undercurrents that are profoundly changing 21st-century American society. 2018 was a year that, upon close inspection, revealed some of the developments and fights that could end up defining our era in the history books.

To make sense of this big picture, I found myself turning — and returning — to the work of nine scholars working in fields broadly related to American politics and society. They weren’t the only thinkers who helped make sense of this year, that list would be too long, but ones whose work I think was particularly urgent.

These scholars helped bring order to the chaos. Several studied the fundamental identity divisions further polarizing and dividing the United States, while another focused specifically on the dark sides of social media’s influence on politics. One is a philosopher who analyzes the nuances of sexism and misogyny; two others are political scientists who study the global decline of democracy and whether America might be next.

Put together, these nine individuals are some of the people best capable of helping us process 2018 — and get a handle on what could happen in 2019.

1 and 2) Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt on the big picture of the Trump presidency

One of the biggest questions surrounding President Donald Trump is how someone with evident authoritarian instincts operates inside a democratic political system. Can it constrain a president who openly admires authoritarians abroad and rages against constraints on his power? Or will the president corrupt the system he’s supposed to serve?

In 2018, we saw a little bit of both. Democratic victories in the midterm elections will put a limit on Trump’s power, allowing both investigations of old scandals — like Trump’s Cabinet members using their posts to enrich themselves — and oversight of any new and troubling behavior by the president.

But the president continued to rail against the independence of the Justice Department, including by replacing Attorney General Jeff Sessions with loyalist Acting Attorney General Matt Whitaker, and did so with the backing of the Republican Party’s leading figures.

Two Harvard political scientists, Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt, have written what is to me the essential book for understanding the push-and-pull here: How Democracies Die, published in January. The book is an analysis of democracies that have “backslid” into an authoritarian system, either through elected leaders seizing authoritarian powers or through a military coup. The book identifies four warning signs for leaders who might be willing to conduct power grabs and applies them to America’s current political situation.

Trump checks all four boxes. But the key concepts in the book to understanding the Trump presidency — and the future of American democracy — are the twin “norms” that Levitsky and Ziblatt argue protect democracy: “mutual toleration” and “forbearance.”

Mutual toleration is “the understanding that competing parties accept one another as legitimate rivals.” Forbearance is “the idea that politicians should exercise restraint in deploying their institutional prerogatives.”

In essence, for democracies to work, parties have to accept that it’s okay if their opponents sometimes hold power and not try to rig the system in their own favor. Trump does not seem to care very much for abiding by these two norms — nor, especially, does the modern Republican Party.

Ziblatt and Levitsky’s work is so important because it reveals the true stakes of the Trump presidency. While it’s easy to get lost in the details of the news out of the White House, there’s a more subtle conflict going on beneath the surface. With each action that Trump and the Republican Party take that breaks with democratic precedent, the illness afflicting American democracy becomes a little more acute. How Democracies Die helps one keep track of how serious the damage is, and what departures from past norms should trouble Americans the most.

3) Kimberlé Crenshaw on the battle over “identity politics” and “intersectionality”

2018 was a year of attacks on “identity politics.”

The term can mean a lot of things to a lot of different people, but generally speaking it means a kind of political appeal or movement that centers on claims about group identity. Typically, people criticizing “identity politics” are attacking the way it’s practiced by progressive advocates for historically marginalized groups, but white people can and do engage in their own forms of identity politics. (See: Trump, Donald.)

Progressives typically argue that “identity politics” is a pejorative used to dismiss any advocacy on issues that specifically affect marginalized groups. Critics of “identity politics,” both on the right and (less frequently) on the left, argue that what the progressives are doing is intrinsically divisive: that their “identity politics” pits Americans against each other, worsening the country’s divides on issues like race and gender rather than ameliorating them.

This is what a loose group of online media personalities and writers who emerged in 2018 — the so-called “Intellectual Dark Web” — has been arguing. This group, including prominent writers like Sam Harris and scholars like Jordan Peterson, are united principally by their distaste for what they see as identity politics run amok. Core to the movement, as the Intellectual Dark Web-sympathetic New York Times columnist Bari Weiss writes, is the idea that “identity politics is a toxic ideology that is tearing American society apart.”

One of the worst forms of identity politics, they have argued, is “intersectionality”: the idea that multiple facts of people’s identity (class, race, gender identity, sexual orientation, etc.) affect their experience of the world in simultaneous and intersecting ways. It can be used both to describe the unique effects of having a certain set of identities, whether they’re largely oppressed (a poor black trans lesbian) or largely privileged (a wealthy white cisgender man).

The language of intersectionality is popular among liberals and on the left, used to denote the speaker’s attention to the subtleties of structural oppression. It’s become so mainstream that even Hillary Clinton cited it during the 2016 presidential campaign.

Meanwhile, critics of so-called identity politics, like prominent Intellectual Dark Webber Ben Shapiro, argue that this is one of the poisons infecting the left today. “Intersectionality,” Shapiro says in a Prager U video, “is a form of identity politics in which the value of your opinion depends on how many victim groups you belong to.”

But actually understanding intersectionality requires going back to the work of the woman who coined the term: Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, a law professor with dual appointments at Columbia and UCLA. Crenshaw’s original work on the topic, in the late ’80s and early ’90s, defines intersectionality not as a positive political doctrine — like liberalism or conservatism — but rather as an analytic frame for understanding very specific experiences of oppression.

“I should say at the outset that intersectionality is not being offered here as some new, totalizing theory of identity,” she writes in a 1991 article. “My focus on the intersections of race and gender only highlights the need to account for multiple grounds of identity when considering how the social world is constructed.”

The political implications, Crenshaw argues, are not that people’s “value” is determined by their identity in some absolute sense, but rather that activists and politicians often fail to develop an agenda that’s adequate for everyone in the groups they claim to speak for:

Crenshaw is still writing and speaking — here’s an August interview with her on the current political controversy surrounding “intersectionality” — but it’s worth going back to her original work to understand not only the nature of oppression, on which Crenshaw is still insightful, but the actual arguments of the so-called “identity politics” left as opposed to the caricatured version presented by the newly popular Intellectual Dark Web.

4) Kate Manne on the Brett Kavanaugh fight

The hearings on professor Christine Blasey Ford’s allegations that then-Judge Brett Kavanaugh had sexually assaulted her in high school riveted and divided the country. Kate Manne, a philosopher at Cornell, helped us make sense of it all with her illuminating analysis of what was really going on.

In an op-ed for the New York Times and an interview with Vox’s Sean Illing, Manne drew on her book Down Girl — a rigorous analysis of the concept of misogyny published last year — to explain why so many gave then-Supreme Court nominee Kavanaugh the benefit of the doubt despite telling some obvious fibs and furiously refusing to answer legitimate questions.

The hearings, Manne explains, were an example of a phenomenon she calls “himpathy”: “the inappropriate and disproportionate sympathy powerful men often enjoy in cases of sexual assault, intimate partner violence, homicide and other misogynistic behavior.”

Himpathy is an outgrowth of a society where men are understood to enjoy natural advantages by virtue of being male. Male pain is treated as more important than female pain — not by everyone nor necessarily consciously, but through subtle psychological and social mechanisms. In Manne’s analysis, our society isn’t merely biased against women, but rather actively generates backlash against women who challenge men and male dominance.

These are the conditions that led some Republican senators to focus on the damage Ford did to Kavanaugh’s career and reputation, rather than on her alleged assault.

“There is some interesting social science that shows that if you’re disposed to sympathize with someone beforehand, and that person is in a confrontation with someone else who you’re not disposed to sympathize with, you tend to be way more aggressive toward the person you don’t understand,” Manne told Illing.

“I think the fact that the male perspective is primary in our culture causes a lot of hostility toward women who come forward and testify against them in these cases, offering a challenge to their otherwise good names or hitherto good reputations, which is of course what breaking silence involves.”

For an example of what Manne was talking about, look no further than a now-famous rant delivered by Sen. Lindsey Graham during his time allotted to questioning Kavanaugh during the hearing.

“I cannot imagine what you and your family have gone through,” Graham told Kavanaugh. “This is the most unethical sham since I’ve been in politics and if you [Democrats] really wanted to know the truth, you sure as hell wouldn’t have done what you’ve done to this guy!”

Graham’s speech, part of a broader Republican emphasis on Kavanaugh’s perspective at the expense of crediting Ford’s story, were products of “himpathy” stacked on top of partisan interest.

“I think the rush to take Kavanaugh’s perspective sympathetically and the way that it comes at the expense of a female perspective is symptomatic of something much broader and really pathological in our culture,” Manne told Illing.

5 to 7) John Sides, Michael Tesler, and Lynn Vavreck on the midterm elections

After most (though not all) of the dust had settled from the 2018 elections, we were left with a new balance of power: a massive swing in the Democrats’ favor in the House of Representatives and a modest gain for the GOP in the Senate.

Part of the House result is explained by Trump’s overall unpopularity, and a lot of the Senate result reflects an unfavorable map for Democrats. But if you dig deeper into the numbers and look at the actual demographics of who voted for whom, what you find in 2018 are overall patterns similar to the 2016 result, just quite a few points more favorable to Democrats in key districts and nationally.

Republicans did well with rural voters, white Southern voters, and low-educated voters, while Democrats won among city dwellers, nonwhite voters, and highly educated white suburbanites. The strength of these divides led to some consequential results, like Republicans’ sweeping victory in the Missouri Senate election or Democrats flipping every House seat in California’s traditionally Republican Orange County.

Identity Crisis, a 2018 book by leading political scientists John Sides, Michael Tesler, and Lynn Vavreck, is the best guide to understanding why these demographic divisions are so stark and getting starker. The book is framed as a postmortem of the 2016 presidential election, but is in fact a sweeping account of the big picture in American politics over the last several decades.

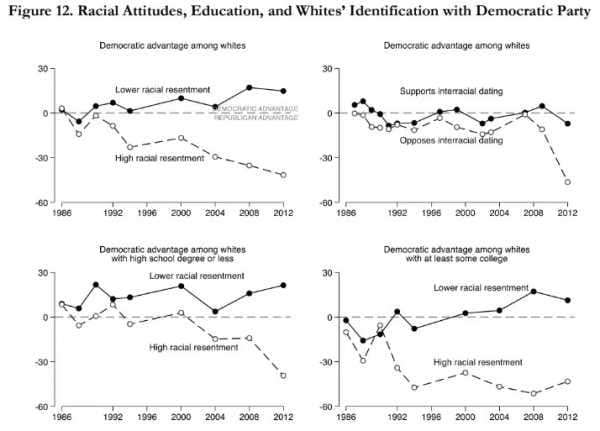

American politics has, they show in the book, has been racialized for a very long time. The civil rights movement sorted black voters into the Democratic Party and pushed racially conservative white Southerners to defect to the GOP. Democrats’ friendliness to continued mass Hispanic immigration, and growing GOP skepticism, further polarized the electorate on racial lines.

Barack Obama’s victory, the visible symbol of a changing America that no voter could ignore, took all of these latent divides and turbocharged them. The result, Sides, Tesler, and Vavreck argue, was a collapse in Democratic support among white voters without college educations.

“Whites who did not attend college were evenly split between the two parties in Pew surveys conducted from 1992 to 2008,” they write. “But by 2015, white voters who had a high school degree or less were 24 percentage points more Republican than Democratic (57%-33%).”

This isn’t a class divide in the traditional sense; there are plenty of relatively high-income whites without college degrees (think of a successful, self-employed plumber). Rather, the “diploma gap” tracked measures of racism and racial resentment more than anything else. Democrats lost huge amounts of ground among non-college whites with conservative racial attitudes, while staying the same or even improving among those with more progressive views. (There’s similar evidence on how views on immigration by nonwhites affected partisanship as well.)

Donald Trump won the presidency by appealing, nakedly, to these divisions. His rhetoric on Mexican immigration, Muslims, and African Americans appealed to the kind of low-educated, rural white voters who had fled the Democratic Party. While it turned off more educated voters who tend to have more racially progressive views, the effect wasn’t large enough for 2016 Democratic challenger Hillary Clinton in a few key areas of the country.

The 2018 midterms represented an extension of this battle. Democrats campaigned on bread-and-butter issues like health care, while Trump’s outsized media presence and insistence on his issues — like the so-called migrant caravan — practically ensured that the debate would be a referendum on Trump’s brand of politics. The Trump strategy was to continue polarizing the electorate along identity lines and to hope for a repeat of 2016.

This worked, to a degree. Republicans who ran Trump-like campaigns on identity issues, like Ron DeSantis in the Florida governor’s race, were rewarded by the rural and non-college white electorate. It also helped defend some Republican House seats in the South, where statistical studies suggest racial identity issues are particularly important for white voters.

But this time, the Democratic dominance among minority voters and gains among more educated whites more than offset the losses. Democrats even managed to claw back some of Trump’s 2016 gains in Midwestern states, like Wisconsin and Michigan, that were billed as the archetypal places for blue-collar Trumpism to succeed. The president’s identity politics helped him consolidate his base, but it also cost him a fair number of voters — enough to lose the House of Representatives.

These divisions are deeply, deeply rooted — to the point where I think you can say America is in a kind of “cold civil war” — and will almost certainly shape the 2020 election and, quite plausibly, the next few cycles after that.

“We’re seeing the emotionally charged politics of race and immigration emerge in lots of states and districts — even without Trump on the ballot,” Sides told me in an interview shortly after the election.

8) Carol Anderson on the war on voting rights

During the 2018 campaign, Republicans did a number of things to make it particularly difficult for minorities to vote.

In North Dakota, home to a tight Senate race, a new law requiring that all voters have a residential address has made it harder for thousands of American Indian voters (typically a Democratic constituency) to vote. The Republican-controlled North Carolina legislature passed a law that led to the closure of 20 percent of early voting locations.

Brian Kemp, the ultimately successful GOP gubernatorial candidate in Georgia, was Georgia secretary of state during the campaign — a job that includes supervising the conduct of elections. Kemp used this position to set up an unfair playing field, launching spurious investigations into Democratic “hacking” of the election and placing a disproportionate number of black voters’ registrations on hold. Rick Hasen, an expert on electoral law at the University of California Irvine, called Kemp’s conduct “the most outrageous example of election administration partisanship in the modern era.”

This can’t be understood at the purely local level, as something happening in specific states without national sanction. For years now, Republicans have been using tools like voter ID laws and gerrymandering to rig the electoral system in their favor by suppressing minority votes and packing minority voters into a handful of districts. No leading Republican, from Trump on down, has condemned the attempts by candidates like Kemp to push this even further — and that sends a clear message as to its permissibility.

Carol Anderson, a historian at Emory University’s Department of African-American Studies, links the growth of Republican undemocracy to an even longer (and more disturbing) historical tradition.

Her 2018 book One Person, No Vote is a careful documentation of the ways in which Republican voter suppression efforts disproportionately and specifically affect minority voters. Seemingly neutral things like purging recent nonvoters from the rolls have “horrific effect on voter registration, especially for minorities,” making it harder for them to vote when they do want to. Overall, she writes, the impact has been profound.

“Rigging the rules to suppress or dilute the vote of millions of citizens to affect the outcome of an election has come almost naturally to many of these politicians and public officials,” Anderson writes. “Tweaking a line here or creating a longer line there has displayed the high-tech wizardry of ‘blunt-force computer-driven’ gerrymandering and the low-tech, traditional means of starving minority communities of resources necessary to participate fully in American democracy.”

This can be incredibly explicit. In 2016, North Carolina Republicans tried to defend a gerrymander that neutered the state’s black vote by arguing that it wasn’t targeted along racial lines, but rather partisan ones. It just so happened that the Democrats they wanted to disenfranchise happened to be black!

Anderson’s new book, and her 2017 volume White Rage, show how difficult it is to separate out our current political situation from the legacy of Jim Crow’s racial apartheid system. The Republican war on the fairness of American elections is, by its nature, a project that targets one of the core victories of the civil rights movement.

9) Zeynep Tufekci on the baleful influence of social media

Social media had, for most of the past two decades, been seen by many as a politically liberating technology. In 2018, the platforms looked less like a solution to the major problems in American politics and more like part of the problem.

Few analysts were as sharp at interrogating social media’s impact on our democracy as Zeynep Tufekci, a professor at the University of North Carolina. Her 2017 book, Twitter and Tear Gas, looked at the impact of social media on protest movements, both in terms of how it enabled protest organizing and how authoritarian states manipulated new technologies to cement their hold on power. In 2018, her most interesting work (to my mind) focused on the platforms’ algorithms — how social media’s tool for personally tailoring content to individual users has bred political extremism.

She conducted a kind of experiment on YouTube after watching footage of some Trump rallies, looking into how watching certain videos would shape her algorithmic recommendations. She summarized the results in a bracing New York Times op-ed:

The reason, she explains, is the site’s algorithm. Google (which owns YouTube) wants people to spend more time on the site, as more videos viewed means more ads viewed, and thus more money. It seems, according to Tufekci’s research, that the algorithm determined that people spend more time on the site if you show them progressively more radical content. Therefore, YouTube’s algorithm is practically designed to radicalize its users — and hence poison our politics.

Tufekci expanded on this argument in an August podcast with my colleague Ezra Klein, which I recommend. She also linked her argument about the corrupting influence of the advertising-driven revenue model to a whole host of other social media woes in a year-end piece for Wired:

Put together, Tufekci’s work offers a kind of master theory of what went wrong for social media — why what was once seen as America’s most innovative industry has now become one of its most hated. It’s a great guide to how we talk about politics today — and how the means we use to talk about politics is in fact changing politics itself.

Sourse: vox.com