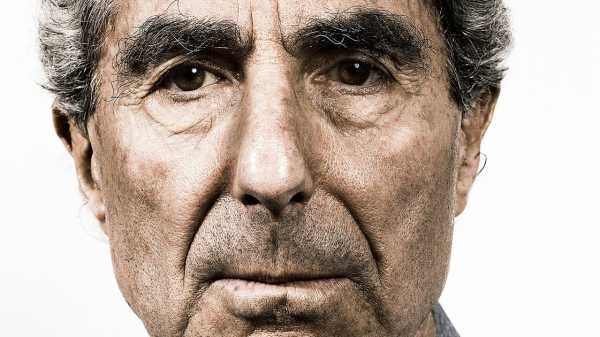

In the fall of 2007, I sat down to try to write a letter to Philip Roth, whom I’d never met. I’d started many letters to him in the past, only to put each aside, newly frustrated by my inability to write the letter I had in mind. But the more time that I let pass without writing to him, the more it bothered me that a certain longstanding gratitude and affection had gone unvoiced. So I explained to him that in his books I found a peculiar, sustaining solace. That, although there were other writers whose work I returned to often, no matter how much I loved them, they didn’t provide me with the very particular thing that he did. What was it? This was the difficult bit to express. “I suppose it has something to do with a certain force of life that everything you write seems to throw off,” I told him, “as well as the promise that such aliveness can exist in something that sits so aside and seemingly apart from life (or so it seems up in one’s writing room); perhaps, even, has a better chance of existing there. Something to do with your lifelong examination of the writing mind, its needs and paradoxes, its incompatibility with so much else, and also its fierce pleasures. And it has everything to do with how, reasonably and unreasonably, I feel at home in your books.”

I told him that I always found encouragement in his work when I most needed it. And what good company he had been to me for so much of my life. At the end of the letter, I told him that I had often been struck by a sharp loneliness whenever reminded of the fact that he wouldn’t always be there, up in Connecticut, writing. “I felt it again,” I told him, “when I read that you are now revisiting Conrad, Hemingway, and the others for the last time around. I suppose it isn’t any longer just your words but their consolidated shape—the idea of you—which has brought me such comfort all these years, and I expect I won’t know quite what to do without its reassurance.”

A reply arrived in the mail, with a telephone number. I called. “So,” he said, “are you at your desk right now?” “Yes,” I said. “Writing?” “Finished for the day.” “Good for you.” “It had to come to an end at some point,” I said. He paused. “No, it doesn’t,” he said, and that was the first time we laughed together. Plans were made to meet the following afternoon.

I arrived on the Upper West Side an hour early, wandered around, then sat on the floor in Barnes & Noble, rereading the beginning of “The Dying Animal.” Which only renewed, refreshed, and refined my fear of meeting the great writer, whom I’d been reading since I was twelve. As always when I’m nervous, my hands became cold. I rubbed them together so that I wouldn’t shock him when it was time to shake hands.

And then there he was, already seated at a table in the back, and, after enduring his stare for a few moments, I was quickly put at ease. I asked if he had written that day. He hadn’t; this was soon after he had finished “Indignation” and before he had started “The Humbling,” and he was still casting around for an idea. “It’s terrible,” he said. “I’m a complete amateur. I have no idea how to do it. How do you write? What is a story? ‘Is this a story?’ I ask myself. On the way here I found myself wondering, What is a novel?” He had already written twenty-nine of them by then, but to him the process had not lost its mystery and could still evoke awe. I remember thinking then that that was the secret, that was how it was possible not just to keep at it for so long but to transform oneself again and again and endlessly reinvent one’s art.

But it wasn’t only Philip’s humility that set me at ease. It was also his warm and ready laughter, his avidity for all subjects, his openness, and, perhaps most of all, the sincerity and absorption with which he listened. It won’t come as a surprise to anyone that Philip Roth could really hold up his end of the conversation. But, between the stories and the reflections, the high jinks and the brilliant analysis, he was also the most generous audience one could hope to have. The joke he handed to Zuckerman—“Other people. Somebody should have told me about them long ago”—was never more ironic than when you were sitting opposite him, trying to answer questions about your experiences and impressions that no one else had thought to ask. This deep, attentive interest was fundamental to him, and was as pressing as ever, even if he no longer needed the material. Though, naturally, he still had a strong taste for it: “Have you used that? You should.” Or, if the spontaneous good bit came from him: “Go on, take it. If you can pick it up and carry it out of the room, it’s yours.”

That first afternoon, we talked about our childhoods; about the usefulness of invoking Benjamin Franklin when trying to sell life insurance; about Saul Bellow, Joseph Brodsky, and Sharpe James, the onetime mayor of Newark who was convicted of fraud; and about the regret, nearly universal among writers, of not having become a doctor instead. But, most of all, we talked about the intense, exhausting struggle that is writing. “I was hoping you would tell me that it might get better,” I said. “Well,” he said, “I'm here to tell you I don’t think it’s going to get better.” “Thank you, Dr. Roth,” I said. “That’s right,” he said, “your half hour is almost up, and that’s your prognosis.” That afternoon, I came away with a piece of paper on which he had written a short list of commandments to hang above my desk, the last of which read, “IT’S NOT GOING TO GET BETTER. RESIGN YOURSELF TO THIS.”

I’ve been reading Roth for thirty years, and in that time his books have come to mean very many things to me. I may never have found myself in them, but I have always discovered myself there. What do I mean? Simply that, in his pages, I have not found a woman exactly like me, who thinks and acts and moves through the world as I do. But then I never went looking for my likeness there, just as I never hoped or expected to find myself in the work of Samuel Beckett, Thomas Bernhard, or Bruno Schulz, or, for that matter, Clarice Lispector or Alice Munro. What I look for in literature—insofar as I look for anything more than coming into a new or richer understanding—is the chance to be changed by what I read. Isn’t that what we mean when we speak of being moved by art? The old position is disturbed; you leave in a different place than you were in before; in very few cases, you come away with the sense that you must change your life. I have experienced all those things when reading Roth. But my attachment to his work is born of something even deeper. When I say that I discovered myself in his books, what I mean is that, novel by novel, decade by decade, I came to know myself through them. When many of the struggles that his work so passionately grapples with came to be, as the years passed, my own struggles—the desire to seize one’s freedom, to overthrow whichever limits and constraints, without abandoning that to which we owe loyalty and love (what strong, independent person wouldn’t recognize herself in that conflict?)—I already knew, from him, a great deal about what it is to wrestle, and to persevere. Not how to solve the argument but how to keep it alive. Not just to withstand the discomfort and the tension of questioning but to make a life there.

And so, in the last years, it sometimes still came as a surprise to pass through the door of his apartment and find the man who took as an epigraph a line from Kierkegaard—“The whole content of my being shrieks in contradiction against itself”—sitting so peacefully in the late-afternoon sunlight. He would want you to listen to a piano piece by the composer Gabriel Fauré, which you’d do together, for fourteen minutes, each of you watching the changing sky through the enormous windows. He would be quick to joke, quick to recount, to explain, to investigate, to disagree, to hop up to get a book, a photograph, an old letter, to sketch a deft verbal portrait or do a dead-on impersonation, to press a bottle of his favorite grape juice on you, or a copy of a book titled “Galut” (which he wanted returned, by the way)—all with a sense of peace and fulfillment that would be remarkable in anyone but stretched the limits of credulity coming from the man considered the maestro of agitation. And yet should it, really? Wasn’t it the nearly absurd but ultimately inevitable and deeply moving end that Roth, and only Roth, could have dreamed up? Wasn’t it just like Roth, having wrestled for sixty years, having gone as far into wrestling as one can go, to apply himself, with all his intelligence, energy, and curiosity, to the other extreme? To peace?

On one of those peaceful days, four years ago, Philip rode the elevator down with me from his apartment, and as we descended the floors, preparing to say goodbye, he spoke to me about the shape of his days, and how he was sometimes suddenly struck by the awareness of being still present, still attentive, still alive. He said it so beautifully that when I got home I asked him if he could write down for me what he’d said, so that I wouldn’t forget it. His reply came back quickly. I quote it here in its entirety:

I think I said that I am struck by the fact that I’m still here. I become intensely aware of being aware of whatever I am reading, of whatever I am looking at, of whoever may be talking to me. It just seems to me extraordinary that I should still be alive doing these things that I have been doing from as far back as I can remember. I am still here, still doing. Sometimes, walking outside, I think that I have been walking under this same sky all my life. It’s an odd and comforting feeling of posthumousness, that all this is coming after my life but is still my life, a posthumousness achieved without dying. Maybe I’m saying that there is a renewed freshness enveloping me that is unaccountable, an emphaticness now lent to time-worn things, a constantly recurring newness just on the brink of it’s all disappearing. Maybe all I’m saying is that I know myself to be living at the edge of life, so that, as a consequence, something previously concealed…. No, this isn’t it. Is it the fear filtering in as ecstasy? The thrill of still having what I am soon to lose? One is always intermittently stunned to be alive. Well, now it’s not so intermittent. Years ago I stumbled on a phrase—I long ago forgot where—that captures, in its grandness and its vagueness, this situation in which I now find myself and for which I have had no preparation. “A full human being strong in the magic.” I am speaking about a recurring sense of being strong in the magic at just the moment I am to be stripped to the bone (and far beyond the bone) of all the fullness I have ever had as a human being who lives in time. I am to cease being in time and of time, which is the ultimate magic. My last moments in time. Maybe that’s the ecstasy now.

This piece was expanded and adapted from an introduction delivered on the occasion of Philip Roth’s last reading, at the 92nd Street Y, in 2014.

Sourse: newyorker.com