When I was a teen-ager, I’d often ride my bike from the suburb where I lived into downtown Denver. I was searching for true West, or at least a truer West than my neighborhood. I snapped pictures with my Kodak Instamatic, which were mostly terrible. But after visiting the vast and magisterial exhibition “American Silence: The Photographs of Robert Adams,” at the National Gallery of Art, in Washington, D.C., I couldn’t stop thinking of my photos, or my feeling that true West would always lie west of where I was.

Robert Adams is best known as a photographer of the West—the beautiful West, the degraded West, and the beautifully degraded West—but he was born in New Jersey in 1937. His father taught him to love the great outdoors. He was ten years old when his family moved to Wisconsin and fifteen when they moved to Colorado. In 1963, after dropping his dream of becoming a minister, Adams, an English professor in Colorado Springs, discovered photography.

In the decade of his photographic awakening, Adams devoured all the issues of Alfred Stieglitz’s Camera Work, pored over “This Is the American Earth,” a book of nature photographs, and bought a print of Ansel Adams’s “Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico.” (The two men are not related.) He photographed the old churches and graves left by indigenous and Hispanic communities in southern Colorado, the grasslands of northeastern Colorado, and the suburbs of Denver and Colorado Springs. He focussed on what he viewed as nature’s gift—“the silence of light.” He made richly toned black-and-white photographs of turbulent skies tumbling over grassy plains. Occasionally, pinched between the natural elements, there were signs of civilization—dark blips along the horizon or dusty ribbons of road running poetically to a vanishing point. Nothing scary, nothing ugly. In one photo, Adams’s wife, Kerstin, exults on a prairie in Keota, Colorado. The picture depicts a tenancy as light as the wind.

But the more Adams looked and photographed the more he saw not just the gift but the threats to it. The Denver suburbs, including those he’d inhabited, Longmont and Wheat Ridge, were spreading unchecked through the plains and the foothills, laying waste to the West. Adams didn’t look away. His working motto became “Go to the landscape that frightens you the most and take pictures until you’re not scared anymore.”

He hasn’t stopped yet. Unlike the many ecologically minded photographers who aimed their cameras above and beyond the trash heaps and tract houses, Adams vowed “not to use the sky . . . to rescue the land.” Instead, he focussed on the desecration. As the exhibition’s curator, Sarah Greenough, writes, his new subjects included “housing developments, mobile homes . . . drive-in movie theaters, gas stations, and strip malls . . . highways, medians, overpasses, parking lots . . . littered fields, empty lots, and spindly trees.” He gave up his large-view camera and bought a small Hasselblad. He abandoned Ansel Adams’s rich tonal scale. And for the next few decades he took the pictures for which he’s best known—those sad documents of suburban life and compromised landscape that are reproduced in such books as “The New West” and “What We Bought.”

John Szarkowski, the Museum of Modern Art’s director of photography, saw in Adams’s “dry as dust” photographs something important. In 1970, he put them in a group show at MoMA; five years later, some of Adams’s photos were part of a revolutionary show at the George Eastman House, “New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape.” One of Adams’s best-known shots depicts a tract house in Colorado Springs, with a bright concrete path curling through a cut lawn. Through the house’s front window, you can see the silhouette of a woman—only a shade, but instantly recognizable. She’s every suburban woman at home alone in the late afternoon, wandering from room to room.

Adams’s photographs aren’t pretty, but they’re honest. When I look at his 1981 bleached-out photo of a child standing by a parking lot, dressed in white socks and black patent-leather shoes, clutching a cup, and enveloped in the shadow of the adult in charge of her, I remember being her. The light and the unhappiness are just right. Adams holds the religiously optimistic idea that facing what is can serve “both truth and hope . . . fact and possibility.” He also believes that light itself, particularly Western light, is somehow redemptive. But his most memorable works, truthful as they are, don’t hold out much hope. Instead, they ask if it’s possible for anyone to live lightly on this once beautiful land.

The only person I can think of who seemed to live that way, at least in my imagination, is Georgia O’Keeffe. She looked great on the land, and the land looked great with her on it. Together they seemed to be harmonized elements, part and parcel of the West that I searched for on my bike and never found. O’Keeffe, like Adams, didn’t come from the West (she was born in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin), but she made the West her own. The land she painted and photographed is often called O’Keeffe country. About Cerro Pedernal, a mesa close to her home, in New Mexico, she said, “It belongs to me. God told me if I painted it enough, I could have it.” Maybe she was joking. Maybe not.

As it happens, the Denver Art Museum now has an exhibition of O’Keeffe’s photos, which makes a great counterweight to Adams’s photos of the West. The two shows couldn’t be more different. The Adams retrospective covers a huge amount of territory, running from just west of the Missouri to the Pacific Ocean, whereas the O’Keeffe show zooms in on her corner of New Mexico. The Adams show has three sections that are quasi-religious: “The Gift” (mostly taken in Colorado), “Our Response” (also largely taken in Colorado), and “Tenancy” (all taken in Oregon). O’Keeffe’s exhibition is organized around her formal interests—reframing, the rendering of light, and seasonal change.

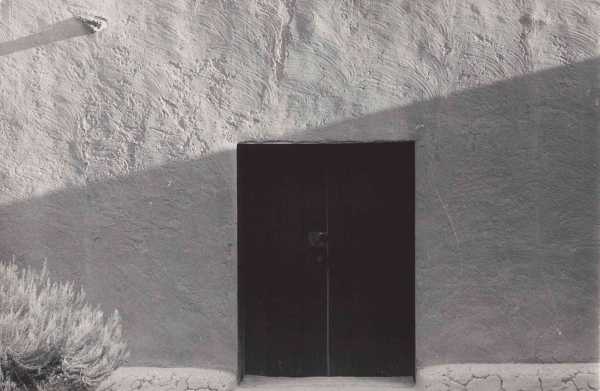

Although O’Keeffe isn’t known for her photographs and barely knew how to operate a camera, the exhibition—“Georgia O’Keeffe, Photographer,” which originated at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, where Lisa Volpe curated it—is fascinating nonetheless. It includes portraits of O’Keeffe taken by her friend Todd Webb, as well as some of her travel pictures. But the real stars of the show are O’Keeffe’s intense studies of her property in Abiquiú—its doors, ladders, walls, and beams. In these, she captures how the West won her over and how she won the West.

O’Keeffe rarely made just one photograph of a scene. She recorded how shapes, shadows, and composition would alter when the sun moved, or the seasons changed, or her camera tilted just a bit. In these formal adventures, her main obsession was the salita door in her house’s inner courtyard. (She often noted that the salita door was what impelled her to buy the property.) She made twenty-three paintings and drawings of that door. As she wrote, “It’s a curse—the way I feel I must continually go on with that door.”

“Salita Door,” Georgia O’Keeffe.Photograph © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

What attracted her were, as Volpe writes, “the formal relationships among all the environmental elements.” By fixating on such relationships—the dark door in the nubbly walls, the spreading sagebrush near the patio stones, and the bright skulls she’d place on her property—O’Keeffe somehow managed to ignore the tragedies that they might embody. Those skulls, she said, never reminded her of death: “They are very lively . . . in relation to the sky.”

Likewise, once O’Keeffe moved into her house and studio in Abiquiú, in the late nineteen-forties, the property’s horrific lineage was pretty much forgotten. As Patricia Marroquin Norby, the associate curator of Native American art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, noted in a lecture last year, O’Keeffe’s picturesque property was once a prison for enslaved Native Americans. One room, nicknamed “The Indian Room,” was a windowless cell with a large wooden door that bolted from the outside. Was that, by chance, the door that O’Keeffe loved?

There can be no innocence living on the land. It doesn’t matter if you focus on beautiful forms, as O’Keeffe did, or on their desecration, as Adams did. The West is where some people go when they begin to despair that things ain’t what they used to be. And the more people move there in search of silence and beauty, the less silence and beauty is there.

In the early eighties, Adams, moving westward again, photographed endangered trees—huddled remains of the eucalyptus windbreaks in Redlands, California, and the citrus groves that stood near the planned developments of Los Angeles. By the nineties, he’d set up camp in Astoria, Oregon, and documented the destruction there: clear-cutting and its residue. His most devastating pictures, which appear in the last section of the exhibition, “Tenancy,” depict the tree stumps of Clatsop County, Coos County, and Columbia County, Oregon, and those monumental stumps that have washed down to the Pacific. These far-West scenes demonstrate once again, as Adams noted, “the perfection of what we were given, the unworthiness of our response, and the certainty, in view of our current deprivation, that we are judged.” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com