In the middle of August, my wife and our two small children went to visit her family in Milan. We arrived at Malpensa Airport at dawn and proceeded to passport control, where the immigration officer, as is customary with public servants in Italy, seemed vaguely put out that we’d interrupted whatever important business he was conducting on his phone. My wife handed over two Italian passports, for herself and our five-year-old, and two American ones. The officer’s mood immediately improved: now we were no longer simply an unwelcome distraction from his private affairs but in the much more interesting category of people he was legally obligated to reprimand. Our two-year-old, he explained gravely, was in violation of the law. As he was an Italian citizen by birth, he required an Italian passport; American passports, he went on, do not carry the names of the parents, and thus he had no way to know that the child, who has my surname, was in fact hers.

My wife, long accustomed to such bureaucratic snares, produced a scan of our son’s birth certificate. The process of obtaining an Italian passport, she explained with a series of complex hand gestures, was so arcane and so onerous! Our two-year-old was born in the first year of the pandemic, she went on, and you know how Italian administrative procedures were: you had to go to one office to get this form, and then another office to get the proper stamp, and the consulate in New York seemed only to be open for such services on every third Wednesday. The man at last permitted himself a commiserative smile: he knew how it was. Look, he allowed, he was a nice guy, so he was going to let us through this time. But we needed to be careful! If we had the misfortune to encounter a more severe officer on our way out, we might be denied exit from the country. When we departed, some two weeks later, we encountered another unusually availing guy willing, of course, to bend the rules just this once.

Lord Byron once remarked that, in Italy, “there is, in fact, no law or government at all; and it is wonderful how well things go on without them.” Today, Italy has a large government with a dazzling number of laws—more than ten times as many as Germany—and the country is full of bright, industrious people who spend an enormous amount of time and energy creatively breaking them. This problem has been a recurring theme for Francesco Costa, a thirty-eight-year-old journalist, who has, over the last few years, become a new-media phenomenon. The Italian media, like the Italian government, is largely made up of stodgy, insular institutions—places more interested in themselves, and the preservation of their own status, than they are in their readers. Costa, who began as an outsider blogger and podcaster, has been credited as a modernizing influence on the role of the reporter in Italian civil society.

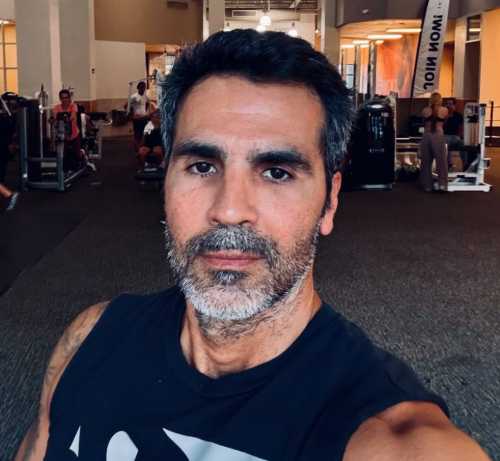

Costa’s daily podcast, “Morning,” which is pronounced with a non-rhotic “R” and a phantom vowel at the end, attracts an intensely devoted audience, especially (but not exclusively) among the country’s liberal élite. The show, which appears under the auspices of Il Post, the news site where Costa serves as deputy editor, is subscriber-only—a rarity in a country where media properties have been slow to adopt new business models that have become common elsewhere. The young Italian novelist Vincenzo Latronico told me, “There are journalists who have been caught copying pieces from elsewhere who are still writing front-page editorials in the main newspapers—it’s such a different culture that it’s hard even to explain. Costa’s journalism would be at a high level in the U.S., but in Italy it’s way above what ninety-nine per cent of the other outlets offer. It’s like he appeared from outer space.” The conceit and the operation of the podcast are simple: Costa’s alarm goes off at 4:45 A.M., he reads up to ten daily papers in the next hour and a half, and he sits at his home computer to record a summary, with dry but opinionated commentary, of the day’s news. He edits out the ambulance sirens from outside his apartment, cuts the episode to thirty minutes, and exports the file himself. “The goal is to come out at 8 A.M.,” he told me recently. He continued, with the national shrug, “Sometimes it’s eight, sometimes it’s five minutes early, sometimes it’s five minutes late.” In a country riven by intergenerational frustration, he has an unusually broad subscriber base: he is at once respected by boomers and parasocially stalked by the youth. (When my wife texted her group chat of Italian expat professionals to say I was writing about him, the response was a flood of heart-eye emojis.) Luca Sofri, one of Italy’s first prominent bloggers and now a colleague of Costa’s at Il Post, told me that it is chiefly Costa’s singular talent that gives what seems like a mere press review such an unusual sway over his audience. “Francesco is simply bravissimo,” he said.

In a perpetual moment of Italian political turmoil, Costa not only aggregates and processes perplexing news—about gas prices or electoral procedures—with rare clarity but also comes at national politics from oblique directions, speaking to the country’s spiritual state with candor and dark humor. I had arrived in Milan at the tail end of the August holidays, when anyone of means abandons the cities to the tourists, and Costa dedicated the prefatory remarks of his podcast one morning to a typical story of Italian coastal melodrama. The episode was called “No Need for a Law for Everything.” Law enforcement had recently begun a “blitz,” scouring the public beaches for illegal “reservations”—places where vacationers have arrived before dawn to put down their towels or umbrellas before going home to sleep until midday, such that people who arrive at the beach at a reasonable hour can’t find a place to take the sun.

The story, he went on, provoked him to consider the activity of law-enforcement personnel who had to conduct these “blitzes.” It wasn’t just the time that they spent finding the offenders but the tremendous waste to follow:

An enormous amount of paper, of signatures, of stamps, of authorizations, of service orders to seize fifteen umbrellas, and then for each of these fifteen umbrellas imagine the amount of senseless paperwork required to say, “We have seized on date X an umbrella with a design of little hearts and flowers,” and imagine this entire operation repeated for every single umbrella, towel, and beach chair that had been seized, on every single beach where the forces of order, instead of dedicating themselves to things we would call much more important, had to devote themselves to these inspections?

Imagine all of that, he instructed his listeners over their morning brioche and coffee, “multiplied for all the other superfluous, redundant, costly bureaucratic operations we’re forced to confront on a daily basis.” His voice, though still dry and deadpan, took on increasing urgency. “We have a law that simply says you can’t put your umbrella on the beach at night but that you can after 6 A.M. But is there a need for a law—must there be a law for us to adopt a comportment of banal manners, that is, don’t occupy a place you’re not using, on a free beach, and do it neither the night before nor at 6 A.M.?” He continued, “Does law enforcement in Norway have to carry out such ‘blitzes’?” He asked, “Or does it not happen because it doesn’t occur to anybody to do such a thing?”

He begged his listeners’ pardon for something that might seem so irrelevant, but he hoped that he had been understood in the spirit he intended. “We’re in an election campaign, every day we’re confronting and adjudicating promises to approve this or that other law,” he said. In the background, “Morning” ’s theme, “Gimme Shelter,” began to play. “Are we sure that all of this comportment—matters of civility and banal good manners—could or should have to be imposed by a law?” Couldn’t it just be up to us, he concluded, “to avoid a situation where law enforcement has to go to the beaches to verify who put his umbrella, or her beach chair, or his towel, on a public beach to unduly occupy a place? In other words, why not just try to regulate ourselves? This is ‘Morning.’ Let’s begin.”

A day or two after that episode aired, I met Costa, who is slender and bald and speaks with a pronounced Sicilian accent, one morning for coffee. We sat at a bar not far from his office, in Milan’s Zona Tortona, an old industrial district renovated to support the fashion and design sectors. He told me, “You can tell we’re journalists because we’re the worst-dressed people at lunch,” though he himself has adopted an offhandedly smart Milanese style. Unlike traditional Milanese brass-and-marble bars—where you can get a coffee in the morning and a drink at night, or vice versa—this was an airy, high-ceilinged space with large tables set out for the laptop cohort.

Costa was raised and educated in Catania, at the base of Mt. Etna. In 2008, he dropped out of journalism school in Rome and pitched a tent in a lakeside holiday community, where he blogged about Obama’s first campaign with unqualified enthusiasm. He sent out letters of inquiry to dozens of newspapers, but at the time he lacked the personal connections necessary to join the media class. Like many other young people of ambition from the impoverished south, he moved in his twenties to Milan, where he mixed with an entrepreneurial cohort of migrant upstarts. He developed a reputation as a young journalist who explained America to his generation of Italians. (His third book about the States, on the problems facing California, came out last week, and is already atop the best-seller lists.) In relatively short order, he was able to sustain his blogging with crowdsourced donations. Inspired by the success of shows such as “Serial,” he turned to audio, first with “Da Costa a Costa” (“From Coast to Coast”), a pun on his name, which became Italy’s first native podcast sensation.

Last year, he started “Morning,” which he describes as a side gig to his role at Il Post, an online-only news organization whose motto is “Cose spiegate bene”—or “Things explained well.” Though he noted that the site, which Sofri founded in 2010, predated the establishment of Vox by four years, he told me that his innovations were nothing new. “I wasn’t being a genius. I was just in touch with what was happening in the U.S., on blogs and in podcasts, and just copied what was working elsewhere.” In Italy, however, this came as a revelation. It was taken for granted that the establishment media wrote largely to and for itself. “They use jargon that people never use and don’t understand,” he said. “They provide no context.” Publications routinely made errors, which they rarely bothered to apologize for or correct. More important, they made no secret of their political affiliations—a center-left senator once described La Repubblica as “our Pravda”—and rarely dwelled on the routine hypocrisy that’s long been endemic to Italian political life. The business model of Il Post was basic precision, firmness, and comprehensibility. “We set out to explain everything like the listener is five years old,” Costa said. It did not take long for him to become one of the few sources that Italians could turn to for straightforward explanations of the deliberately illegible machinations of national politics. In July, the generally popular caretaker government of Mario Draghi—the third unelected banker-technocrat recruited to run the country since the nineteen-nineties—was brought down by the abrupt (and, given that almost all of the parties are now running on a continuation of his economic policies, largely pointless) withdrawal of support by the junior coalition partners, and overnight Costa found himself delivering daily coverage of the snap elections, which are to be held on September 25th.

For anyone who has paid even passing attention to the Anglophone press’s treatment of the political situation in Italy, Costa’s riff on umbrellas and banal good manners might seem like a glib reaction to an impending crisis for European democracy. In the past decade, Italy, along with many of its peer countries, has been destabilized by populist movements on the right and the left. Now it seems to many foreign observers that Italy’s next government will be a Fascist one. Polling has been stable, and a decisive victory is almost assured for a so-called center-right coalition led by Giorgia Meloni, who would be Italy’s first female Prime Minister. It’s not hard to gather why Meloni brings Fascism to mind. The Party that she co-founded, Fratelli d’Italia, arose from the ashes of Italy’s Movimento Sociale Italiano (M.S.I.), the postwar reconstruction of Mussolini’s base. Her party occupies M.S.I.’s former headquarters in Rome, she has retained its symbolism—a tricolored flame—and she frequently refers to “Dio, patria, famiglia,” or “God, country, and family.” Many of her followers have taken up the stiff-armed Roman salute associated with Il Duce, on the flimsy pretext that it’s a hygienic development in the wake of COVID. Mussolini’s granddaughter Rachele is a Party member, and a member of Rome’s city council.

None of these things, needless to say, are lost on the Italian public. But Costa believes that the Fascism trope—promoted not only by the foreign press but by a center-left coalition desperate to gin up support from an otherwise disaffected bloc—is not only overblown but unhelpful. It’s strange that the sole story of the foreign press, he said, on a recent episode, has been to present “every single Italian election as a struggle against the imminent return of Fascism.” This isn’t to say that Costa is under any illusions about what a Meloni-led coalition in power will mean. “There is the very real risk that we will have an extremely right-wing government, especially on civil rights,” he said. “It might not be Fascist, but it’s definitely scary.” Her leadership will be particularly bad for migrants and their children, for whom there is no path to citizenship, and for the L.G.B.T. community; for years, the Italian right has sought restrictions on abortion, and the recent Dobbs decision, in the U.S., has made the prospect of new anti-abortion laws elsewhere increasingly plausible. Costa did not discount the ramifications of cultural regression. The Italian right is unapologetically nostalgist, and their chief aim is to mettere l’orologio indietro—turn the clock back to simpler times.

But there isn’t much more a Meloni administration can do. After Brexit, the Italian right retreated from talk of leaving the E.U. As of this year, Meloni all of a sudden supports Russian sanctions and NATO. She has little room to negotiate on international affairs. The pandemic brought billions of dollars in E.U. relief funds, and Meloni can’t afford to imperil her relationship with Brussels and Frankfurt. Though Italy has run a budget surplus for most of the last twenty years, the country carries a public debt that’s about a hundred and fifty per cent of G.D.P., and it relies on European backing to keep interest rates manageable. If Italy fails to meet the budgetary and administrative reforms mandated by the E.U. in exchange for the emergency pandemic relief, bond rates will escalate and the new government might not even last a year.

“Will Italy be a police state? No,” Costa told me. “Will it be very badly run? Yes.” Everyone agrees that the country has real, serious problems—with pensions, taxes, the courts—and Meloni has offered virtually nothing in the way of tractable proposals to solve them. But Costa no longer has any faith in the center-left, which has governed for much of the last fifteen years without ever having secured a popular mandate or getting anything appreciable done. All those parties know how to do, he said, is sound the alarm about creeping totalitarianism. Under Silvio Berlusconi, the main electoral promise of the opposition was “At least we’re not that dictator guy,” Costa told me. (As he put it in a recent episode, “Those who opposed Berlusconi accused him of following Putinism, of having dictatorial ambitions, that sort of thing—that was legitimate.”) But Berlusconi led the country on and off for some three decades, and, aside from the absolute race to the bottom in popular culture, left virtually no mark at all. (Over the summer, he threw in his lot with Meloni, and if she wins he will return to government once more; in an effort to reintroduce himself to young voters, he recently joined TikTok.) Now the center-left has pivoted to “It’s us or the fascists,” Costa explained. This isn’t unhinged scaremongering—if a coalition between Meloni and Matteo Salvini, the leader of the anti-immigrant Lega Party, gains a two-thirds majority in parliament, as is possible, they could, in theory, rewrite the constitution without a referendum—but their opposition lacks any positive vision of their own to offer voters. Fascism has long given the center-left cover for its own exhaustion and ineptitude; if there’s a relevant lesson for other Western democracies, it might have less to do with Fascism itself than with an exaggeration of the threat it poses. “But disaster is business as usual in Italian politics.” Costa sighed and threw up his hands. “We have these constant debates and nothing ever changes.”

This is precisely the problem. Italy’s political structure was created to prevent any one faction from attaining the kind of power that Mussolini had. As John Foot, the preëminent British historian of Italy, told me, “The constitution makes it very difficult to do very much in Italy. That’s what it was built for, to stop people from doing stuff, and it does the job.” The dream of coalition politics has mostly been reduced to the art of blackmail—“ricatto” is one of the most common words in Italian political commentary. Since the nineties, the government has changed the country’s electoral laws four times, with the hope that something closer to a majoritarian system might make the country more stably governable. One of Costa’s habitual themes is that the most recent election law, which put a hybrid system in place, is so complicated that no one has a clue how it actually works. The upshot, he told me, is that there is no accountability in the system at all. “We can’t pick our representatives, there are no primaries, the leaders of the parties decide everything, we know in advance who’s going to win. This creates a feeling that my vote is totally useless. Whatever I think, I can’t really change anything.”

The only thing that has reliably roused the public from its apathy is novelty. “Italian voters are attracted by what is new,” Costa said. “First Matteo Renzi was new. Then Movimento 5 Stelle was new. Then Matteo Salvini. They all achieve great popularity in a short amount of time and then lose it equally quickly. Now Meloni is the shiny new object in Italian politics. . . . There’s this feeling that the scariest of governments are only going to last a year or two, so how bad could it be?” But Italy’s political paralysis, he gloomily conceded, could have its benefits. “It’s depressing, but, with all of its flaws, it can also be reassuring. Politics in the U.S.A. are a little bit scary—now it’s somewhere where a coup happens?”

For Costa, to highlight the issue of beach towels deposited under cover of night isn’t to abjure politics; as he sees it, the cultural dysfunction of civil society is at once upstream and downstream of the concurrent political dysfunction. As the Florentine political scientist Antonio Floridia has described it, there’s a vicious cycle in which constant lamentations about constitutional inadequacy erode the legitimacy of Italian democracy, and the erosion of Italian democracy sanctions the suspicion that all people can reasonably be expected to do is look out for themselves. The total breakdown in trust has been self-perpetuating.

In the bar, Costa gestured around. “To open a bar in Italy, you have to fill out two hundred forms. And here we are in Milan, the richest and most dynamic and modern Italian city—the rest of Italy makes fun of us for eating sushi and drinking Starbucks—and even here you still have to walk around with cash in your pocket.” Many shops, especially outside of the wealthier cities, don’t take credit cards and won’t give you a receipt, because they can’t afford both to pay taxes and to stay in business—though the loss of that revenue to the submerged economy is part of what keeps taxes so high in the first place. Costa explained, “Everyone makes their own private peace with the fact that the country doesn’t work well.” Cronyism and nepotism have become, under such circumstances, rational strategies for individual survival. Self-interest has been enshrined as statute. He continued, “We had a law that allowed bank companies to send workers into retirement in advance and hire their sons and daughters. Your job here is hereditary!” He continued, “We had this very famous guy, Piero Angela, who was extremely popular on TV—like our David Attenborough. Now the most popular guy on TV is Alberto Angela. To be the new Piero Angela, you have to be the son of the old Piero Angela!” For those who have rigged up their own ruthless way of making things work, there’s no incentive to change the status quo. Costa said, “As we put it, the important thing is that I take care of myself and continue to complain about it.”

Costa acknowledged that the country’s legendary inefficiency is, amid the encroachment of global monoculture, part of its enduring appeal. “You in the United States hate to waste your time, you have drive-throughs everywhere, you love to be organized and efficient. We love taking it slow, la bella vita.” Tourists admire the idea that Italians still buy their bread at the bakery and their cheese at the cheesemonger and their fruit at the fruit stand. But they miss the fact that, to function, Italians need not only a cheesemonger and a fruit guy but an array of personal fixers to accomplish basic tasks. Everyone is accustomed to their own improvisation, and there is no natural constituency for transparency. “There’s no way to evaluate teachers or public workers. The only way to get a raise in the public sector is through seniority—you can’t pay more to talented or hardworking people, so you incentivize people to do the bare minimum. When you get a new job, your co-workers tell you not to do too much, not to surprise the boss, because otherwise they’ll be asked to do the same,” Costa said. That pervasive lack of accountability is one of the reasons that Italian politics offers little hope to Italian citizens, who see politics as just another arena in which the winners are those who deposited their beach chairs the night before.

Costa sees his podcast, and his work in the newsroom at Il Post, as partly an effort to build, if only on a small scale, a community that represents the kind of conscientious civil society he’d like to see. Politicians need to be held to meaningfully democratic standards, and the only way the media will have the credibility to do that is if the media itself is genuinely open to criticism in a new way. “I get constant live feedback, I read every e-mail and every message on social, and when I mess up they let me know,” Costa said. He allowed that it wasn’t ideal for his mental health, but he saw an opportunity to create a community that could stand as a model. “You can easily build a big following every day by just yelling about Salvini. But that’s not what I want. I’m playing a different kind of game.”

He understood that there was the danger that he was flattering his audience—that they, the liberal élite, couldn’t possibly be the ones who went down to the beach before dawn to set up their umbrellas. But they probably had those impulses, he said, and he did, too; absent a sense of the collective, looking out for yourself felt like the only way. He didn’t want to sound sanctimonious. “It can be insufferable if you miss the right tone,” he said. “This is something I do at 6 A.M. in my pajamas. I worry that I pontifico—do you have that word, to talk like the Pope? But I try to be the grownup in the room without being insopportabile, criticizing others without putting myself on a higher level.” He found his own success bewildering, but took it as a sign that at the heart of his relationship with his audience was a mutual sense of fidelity. “I really don’t know why this broad public is listening to this podcast that’s just me, basically,” he said. “But at least I try to demonstrate by my own example.” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com