In the fall of 2017, Talitha Wisner was completing her assigned reading for Practical Ethics—one of Princeton University’s most popular philosophy classes—when she decided to e-mail her professor. In the subject line, Wisner adopted the language of her lecturer, the utilitarian philosopher and ethicist Peter Singer, and typed, “What’s the most good I can do? Using social media to strengthen the movement.”

Wisner, a post-millennial who became vegan for a time under the influence of YouTube videos and Instagram posts, had agreed with that week’s reading—a report about lowering global meat consumption in response to climate change—but she didn’t like the authors’ dismissal of social media. As Wisner relayed to Singer, perhaps social media could be a way for broke college students to spread ethical awareness, through likes in lieu of dollars. At the time, Wisner used her Instagram account to advocate for plant-based living, but the outreach often felt silly. If Singer believed that it was a good idea, she wrote, then she would feel less conflicted. Before ending the e-mail, Wisner asked one last question: “Why don’t you have a public Instagram or YouTube account?”

Singer has long been active on Twitter and Facebook, and between those two platforms he has amassed more than a hundred and forty thousand followers. But, before Wisner suggested it, he hadn’t given much thought to creating any new social-media accounts. “Time,” Singer wrote to Wisner, a few days later, was the main problem, and he just didn’t have any more of it to spare. Before signing off, he added, “Maybe I should look for someone else to organize it for me, though.” Two e-mails and three hours later, Singer had exactly that.

For more than a year, Wisner and her fellow Princeton student Sarah Hirschfield, who joined the effort soon afterward, were the team behind Peter Singer’s Instagram account. (Wisner has since stepped away from the account, and Hirschfield now has full control.) United by their passion for veganism, Wisner, a political-science major from Texas, and Hirschfield, a philosophy major from New York City, have spent many afternoons discussing how to live more ethically. Managing Singer’s Instagram account—an unpaid, invisible, and largely thankless task—is not only a way of “sharing the gospel,” as Hirschfield said, but a logical extension of their ethical ambitions.

Singer, whose key works include “Animal Liberation,” “Practical Ethics,” and “The Life You Can Save,” told me that he “hadn’t looked at Instagram very much, and I still haven’t.” He added, “If the students hadn’t come to me with this suggestion, I may not have started it.” To account for the professor’s largely hands-off approach, Wisner and Hirschfield would send Singer a weekly Word document of draft posts—a sort of offline Instagram—for review.

Sometimes, Singer will suggest a different excerpt of his work. Other times, he’ll request a new image to better reflect the words. The latter, Wisner said, was the most challenging. While Twitter is a natural choice for academics—after all, words beget words—Instagram, a platform that demands compelling or even voyeuristic visuals, can be more of a stretch. Somewhat out of economic necessity, the account relies on open-source stock images to illustrate Singer’s key ideas. Effective altruism—“doing the most good” with the resources you have, as Singer writes—is often represented by impoverished, non-Western children. Animal liberation, which led to Singer’s standing as the founder of the modern animal-rights movement, is depicted by a floundering animal raised on a factory farm. There are also basic shout-outs to other scholars: a portrait of the fellow utilitarian philosopher Henry Sidgwick, a bust of Karl Marx, and a sketch of the Greek philosopher Epicurus.

“We’re operating in this unclear market,” Hirschfield said. “We’re something like an academic-philosophy account, but we’re also like a vegan-memes account.” Then there’s the subject matter itself. For a personal account, topics like poverty and animal cruelty are unusual Instagram fodder—Singer has been told that his account is “very heavy”—and it’s not as if Instagram is spilling over with intellectual philosophers. Because of this, the account has become both an experiment in visualizing ethics and a counterpoint to status-conscious Instagram. There is something jarring and hilarious about scrolling through an Instagram feed of selfies, #sponsored posts, and advertisements, only to land on a stock photo of a pigeon drinking from a water faucet, accompanied by caption about the futility of spending money on things that you don’t really need.

Loading

View on Instagram

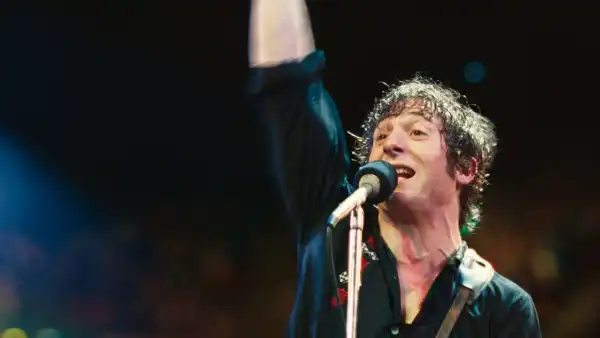

Even for a philosopher, some Instagram rules hold true. Cute animal photos, albeit accompanied by quotes about animal welfare, typically do well. Unsurprisingly, the same goes for photos of Singer himself. There has only been one selfie to date, but Wisner and Hirschfield also posted portraits of their professor, often taken by the pair around campus. The most liked current post shows Singer seated on the Princeton lawn eating an orange beside one of his books. The portraits also align with Wisner’s initial hope that the account would offer its followers an insight into an ethicist’s everyday life. But the “world’s most influential living philosopher,” as Singer is often called, is a reluctant influencer. Although he believes in gaining followers to further the cause, he, unlike many on social media, is wary of his privacy. “I find it quite surprising what some people are prepared to make public through Instagram,” Singer said.

As Wisner and Hirschfield approach their last year of college, I asked them what would happen to the account after they graduate. Hirschfield cited a fear of the “second-generation curse”—if she passes the account onto a new group of students, those students may not be as invested in it as she presently is. Quoting the last line of George Eliot’s “Middlemarch” (and clarifying that it inflates the work she does for the account), Hirschfield said that it is the significance of “unhistoric acts” that contributes to the greater good. Singer’s account—with its cerebral captions and quirky stock images—shows, in a modest way, that ethical considerations can exist, and even thrive, on a platform that espouses so few. If Instagram is to its users what the pond was to Narcissus, then Singer’s posts are pebbles that occasionally ripple its surface.

Sourse: newyorker.com