At the World Livestock Auctioneer Championship, which has been held annually in the United States since 1963, eager contenders gather to show off what they refer to as a chant: a rhythmic, rapid-fire narration that eventually results in the sale of a live, blinking farm animal. A chant needs to convey both the current auction price and the bid required to unseat the leader, but what happens in between—the filler words peppered into an auctioneer’s flow, delivered with alarming velocity—is what distinguishes a functional auctioneer from a master. The best chants resemble song: melodic, multitudinous, triumphant.

The photographer David Williams attended this year’s W.L.A.C., in Bloomington, Wisconsin. Williams told me that he first learned about the practice of auctioneering from Werner Herzog’s 1976 documentary, “How Much Wood Would a Woodchuck Chuck.” “Spending my entire life in urban cities, I was somewhat surprised that not only does this competition still exist but a career in auctioneering is a thriving profession,” he said. “So, I decided to go see what professional auctioneering forty years later looks like.”

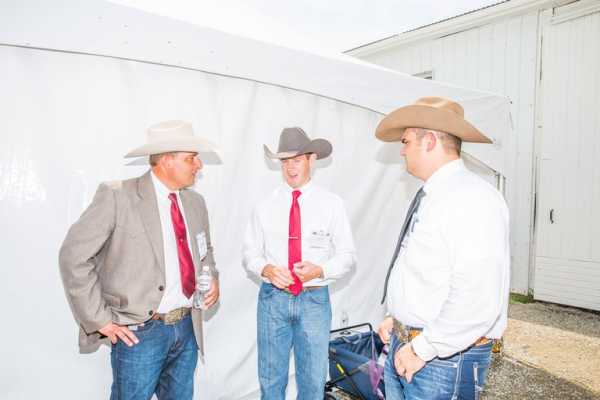

Today, Web sites like eBay have made the auction remote and commonplace—an easy way to acquire both rare and mundane items. But live auctions are a more elaborate sort of ritual. Champion auctioneers carry themselves with an air of solemnity and order; they are sometimes referred to as “colonels,” an honorific that dates back to the Civil War, when military colonels auctioned off the dry goods pilfered by soldiers. American flags are omnipresent in livestock barns. Before and during each event, there’s often a lot of talk of freedom (a reminder, perhaps, of the auction block’s odious past as a place for selling human beings). The men in Williams’s photos are pink-faced and solidly built. They wear cowboy hats, sport coats, scuffed boots, and blue jeans.

This year’s champion, Jared Miller, of Leon, Iowa, took home a customized 2018 Chevrolet Silverado truck to drive for his yearlong reign; he also won six thousand dollars, a world-champion belt buckle, a world-champion ring, a money clip, and a bespoke leather briefcase. In interviews, Miller, like many successful auctioneers, appears personable and polite. When he begins his chant, his mouth only opens so much—when you’re talking as fast as he is, the tongue does most of the work—but what comes out sounds something like a undulating yodel, or a less guttural take on the Inuit tradition of throat singing. Once you tune in to its particular rhythms—and it can take a few minutes to acclimate to the crests and swells—the prices become discernible: “One dollar bid, now two, now two, would you give me two?”

In Williams’s vivid, fascinating photographs and videos from Wisconsin, you can see that there’s something old-fashioned and formal about the proceedings. “Every auctioneer I talked to was from a small city I had never heard of, mostly in rural communities spread across the Midwest, South, California, and Canada,” he said. “Many learned the trade through family who were professional auctioneers, and continued their education at auctioneering school.” In Herzog’s documentary, one man describes learning breathing techniques from a trained opera singer; another recalls perfecting his chants while milking the family cow. “The sense of pride is extremely high,” Williams said. “It’s a very tight community. Winning the competition is a huge accomplishment within the industry, and helps boost their notoriety, which leads to working in larger sale barns across the country.”

The history of American folk art is rife with vernacular traditions that began as chores, but, when perfected, became sublime expressions, worthy of spectacle and celebration: rodeo competitions, quilting contests, and so on. Herzog called auctioneering “the last poetry possible, the poetry of capitalism,” and, indeed, watching the auctioneers rattle off cattle prices with such singular aplomb feels like evidence that even the most mercenary activities can sometimes become beautiful.

Auctioneers board a charter bus from Dubuque, Iowa, to Bloomington, Wisconsin, to compete in the World Livestock Auctioneer Championship.

David Williams

The opening ceremony at the Bloomington Livestock Exchange.

Audience members stand with hands over hearts during the opening ceremony at the Bloomington Livestock Exchange.

Auctioneers head from the holding area to the sale barn to learn who will be competing in the final round.

Bidders fill the seats at the Bloomington Livestock Exchange as thirty-one professional auctioneers compete in the championship.

Chuck Bradley, from Rockford, Alabama, auctions off cattle in the World Livestock Auctioneer Championship.

Auctioneers talk with each other after competing in the World Livestock Auctioneer Championship.

Mennonite children watch cattle move to the sale barn at the Bloomington Livestock Exchange.

Neil Bouray, from Webber, Kansas.

Sourse: newyorker.com