“The story of the Hurricane,” as Bob Dylan once sang, has been told before. It is the tale of Rubin (Hurricane) Carter, the famous middleweight boxer who was convicted and reprieved—twice—of a 1966 triple murder at a bar in Paterson, New Jersey. His wrongful-conviction story was immortalized in Dylan’s song “Hurricane,” from 1975—“All of Rubin’s cards were marked in advance / The trial was a pig-circus, he never had a chance”—and a movie starring Denzel Washington, from 1999, with similarly righteous tones. In 1985, a federal judge overturned Carter’s convictions, and also those of his co-defendant, John Artis; both men had served long sentences. But the ruling didn’t mean that the murder case was solved. Publicly revealing what actually happened that night could bring solace to many—and, possibly, open a huge can of worms.

“Nobody wanted the truth of my findings to come out—not the prosecution and not the defense,” an older man’s voice says in a clip at the beginning of the podcast “The Hurricane Tapes.” The series, produced for the BBC World Service by Steve Crossman and Joel Hammer—“just two sports journalists who love a good story,” Crossman says, in his northern British accent—hopes to solve the case, or at least to offer a plausible counter-theory. (It concludes on April 1st.) “Neither of us have investigated a murder before,” Crossman says, brightly, at the outset. He and Hammer are not podcast veterans, either. They reported “The Hurricane Tapes” for a year, interviewing some thirty people, including the appealing Artis. (Carter died in 2014.) Their freshness of perspective and zeal for the scoop are evident, but the result doesn’t sound like an overambitious whodunit by novices—the podcast is fairly hubris-free, and its narrative scope extends beyond crime-solving. It’s built on a foundation of riveting audio that tells a larger story about the complex and tortured relationship between race, violence, and justice in America.

On the night in question, in 1966, two black men entered the Lafayette Bar & Grill and shot four white people, three of whom died. It was quick and astonishingly bloody. That night, Carter and Artis were stopped while driving home from a club. The shooting’s sole survivor said that Carter and Artis weren’t the shooters, but a petty criminal claimed to have seen them at the scene of the crime. It was a particularly intense moment of racial anxiety in Paterson, Crossman says, and in the country; the murder had shocked the community, and Carter and Artis were ultimately convicted by an all-white jury. The rest has been a decades-long melodrama featuring everyone from Muhammad Ali to Dylan to “a small army of Canadian zealots” that was “beavering away on the case,” Crossman says.

After watching the 1999 movie, Crossman set out to make a documentary about the case. In the research process, he and Hammer met the writer Ken Klonsky, who had published a book about Carter’s spiritual journey, in 2011. This led to the unearthing of a forgotten trove of Klonsky’s cassette recordings of Carter—forty hours’ worth. The excerpts we hear don’t sound like traditional interviews. Mostly we hear Carter talking, and he sounds natural, the sentences pouring out of him with ease, like someone sitting down and dictating a memoir. His manner of speaking is urgent, smart, fierce, with hints of dark poetry. We might not love him as a person, but we like listening to him speak.

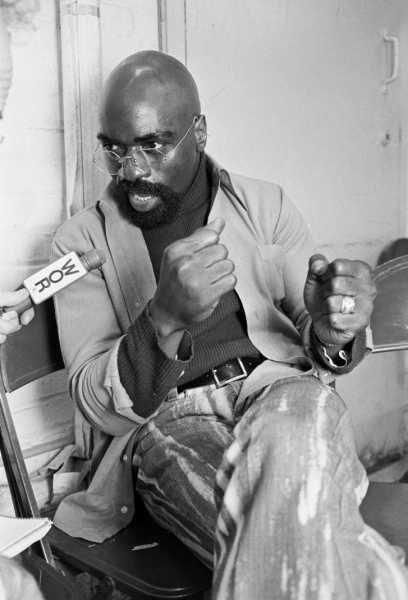

As Carter’s fame grew, so did his notoriety, because of his fury in and out of the ring.

Photograph from Bettmann / Getty

“I’ve been in prison all my life,” Carter says. “I was born with a severe stutter that was a prison. It was my stumbling, bumbling tongue that wouldn’t allow me to participate with groups of people.” If people laughed at him, he says, “the only sound they would hear would be the sound of my fist whistling through the air.” There were other prisons, too. Carter’s childhood, in Clifton, New Jersey, was shaped by poverty and violence. He spent time in a home for juvenile delinquents, joined a gang, joined the Army, discovered boxing.

Crossman and Hammer skillfully show how the violence central to Carter’s meandering life led to a boxing career—and how quickly boxing took him from pariah to hero and back again. At the height of the Cuban missile crisis, he fought a Cuban boxer at Madison Square Garden and swiftly knocked him out; it was a moment of national glory. But, as his fame grew, so did his notoriety, because of his fury in and out of the ring. He was righteously angry about institutional racism, in the U.S. and in South Africa, where he travelled for a fight. “I couldn’t see myself throwing sticks and rocks at people when people were shooting me with guns,” he says. He admired Malcolm X; in interviews in the sixties, Carter said that black people should defend themselves with firearms. He also kept getting arrested—“for assault in a bar, or some kind of foolishness like that,” he says. “Just like these young jitterbugs doin’ today.” Were you actually doing those things? Klonsky asks. “Of course I was!” Carter says. But the foolishness wasn’t a big deal, he said—he was a target, persecuted unjustly by cops.

The podcast is mainly about the murder investigation and the people connected to it, but it feels evident that its resolution matters both for justice’s sake and for the public’s understanding of a story that has come to embody a pervasive form of racial discrimination. (And one that’s been well documented in podcasts.) It doggedly plunges into the nitty-gritty details, contextualizing in a near-literary manner through colorful interview quotes, and it includes welcome moments of whimsy. When an investigator is compared to Javert in “Les Misérables,” they play a little Schoenberg; before a revelatory conversation in a diner, Crossman provides a “listener note” about upcoming sounds of cutlery and chewing. They seem to be having fun with the form: at one point, when Artis is describing being pulled over with Carter, they cut to Carter delivering his own line of dialogue, which is taken from his version of the story in the tapes. And the Dylan song keeps kicking in, like an anthem. (The more we learn, the more we might imagine revisions to its lyrics.)

The producers don’t feel the need to idealize Carter, or themselves. They’re proud of the work they’ve done and sell it pretty hard: “These grainy old cassettes were sitting untouched in a Boston basement,” Crossman says, of interviews from a decade or so ago; he also says that they talked to everyone important to the case except Carter, which seems generous. But I don’t especially care about such hype, because Crossman sounds much more fired up about getting to the bottom of things than he does about claiming credit for what he finds. After ten episodes, I don’t detect the needy reporter-as-hero quality that mars so many investigative podcasts and distracts the listener from the subject at hand.

To what extent Carter was a target and a victim is a key question. A related question is the role of a parallel story about that night in Paterson, long underexamined and possibly suppressed, which Crossman and Hammer seem to be piecing together in real time. I’m anxious to hear what follows. It could unlock this case; it could reveal ugly truths about the justice system; it could further complicate our understanding of Carter. And the story of the Hurricane, told in a protest song, in 1975, and a movie drama, in 1999, could take its definitive form in a podcast, in 2019—both because of the skill of the producers and because the world is ready to hear it.

Sourse: newyorker.com